| Church Manuals | |

| Come Follow Me Manual | View |

| Scripture Helps: OT | View |

| OT Seminary Manual | View |

| OT Institute (Gen-2Sam) | View |

| Pearl of Great Price Manual | View |

| Scripture Reference | |

| Bible Dictionary | View |

| Topical Guide | View |

| Guide to the Scriptures | View |

| Church Media | |

| Gospel for Kids | View |

| Bible Videos | View |

| Church Publications & Library | |

| Church Magazines | View |

| Gospel Library | View |

Is Any Thing Too Hard for the Lord?

5-Minute Overview

This week holds some of the most dramatic moments in all of scripture. God visits Abraham at Mamre and asks the question that becomes our theme: 'Is any thing too hard for the LORD?' Sarah laughs at an impossible promise — and then Isaac ('he laughs') is born. Abraham intercedes for Sodom and is tested on Mount Moriah. Lot's wife looks back. And Sarah is buried in the first land Abraham ever owns in Canaan. Every story this week asks the same question: Will you trust God with the impossible?

Weekly Resources: Week 09

Genesis 18–23

Feb 23–Mar 1

“Is any thing too hard for the Lord?”

Official Church Resources

Video Commentary

Specialized Audiences

Reference & Study Materials

"Is any thing too hard for the LORD?"

I've been sitting with that question all week, and I want to be honest with you: it's one of those verses I've read a hundred times without really hearing it. It sits so comfortably in our spiritual vocabulary — of course nothing is too hard for God — that we can nod past it without letting it cut.

But this week, I think the text wants us to stop nodding.

Because the question wasn't addressed to theologians debating omnipotence in the abstract. It was addressed to a ninety-year-old woman who had just laughed — laughed! — at the idea that her body could do what God said it would do. Sarah's laughter wasn't irreverent. It was the sound of someone who had lived too long with disappointment to risk hoping again. And God's response wasn't a rebuke. It was an invitation: Is anything too wonderful for Me?

That Hebrew word — pala (פָּלָא) — doesn't really mean "hard" the way we use it. It means extraordinary, surpassing, beyond what you thought possible. God wasn't asking Sarah whether He was strong enough. He was asking whether she could imagine a world bigger than her disappointments.

This week we walk through some of the most dramatic chapters in all of scripture. We'll watch Abraham welcome divine visitors under the oaks of Mamre and then bargain boldly for Sodom's survival. We'll flee with Lot through fire and sulfur while his wife turns to look back — and becomes a monument to divided loyalty. We'll hear Sarah's laughter transform from incredulity to joy when Isaac arrives, the child whose very name means "he laughs." And then, in the devastating silence of Genesis 22, we'll climb Mount Moriah with a father and his son, carrying wood and fire and a question that echoes across millennia: Where is the lamb?

Every story this week asks the same thing in a different key: Will you trust God with the impossible? Will you walk forward without looking back? Will you let Him do what only He can do?

Let's find out together.

Welcome to the New CFM Corner!

If you're a returning reader, you might have noticed things look a little different around here. A lot different, actually.

This is something I've been planning for a while. The issues I was having with the old hosting platform were driving me nuts — limitations on layout, formatting headaches, slow load times, things breaking for no reason. I knew I needed to rebuild the entire site from the ground up.

A little confession: when I started this website four years ago, I barely knew how to find a folder on my hard drive. And that is not an exaggeration. I've learned a lot since then, and it was time to put that learning to work.

I am so excited with how this has come together. You'll find a cleaner layout, faster pages, better mobile experience, and some exciting new features — including a brand new Hebrew Language section for those wanting to dip their toes into biblical Hebrew. And we have some exciting things currently in the works that are still a bit down the road, but they are going to be so helpful for our scriptural journeys together.

Thank you for being here. Thank you for studying with me. Now let's dig in.

A full study guide is prepared with six files, interactive charts, and this Weekly Insights document. Here's how to find what works best for you:

| If you are... | Start here |

|---|---|

| Short on time? | Start with the Week Overview — it gives you a complete reading summary, central themes, key figures, and a suggested reading approach for every time level. Pair it with the CFM Manual lesson for a focused, manageable study session. |

| Love deep study? | Historical & Cultural Context — The ancient world behind these stories: ANE hospitality codes (why Abraham's welcome matters), Sodom archaeology (including the remarkable Tall el-Hammam airburst evidence), Akedah traditions in Judaism and Christianity, Hittite land sale customs, and the Cave of Machpelah. Key Passages Study — Five passages in extraordinary detail: the divine announcement, Sodom's destruction, Isaac's birth, the Akedah, and Machpelah. Each includes Hebrew word analysis, literary structure, ancient context, and Latter-day Saint connections. Word Studies — Six key Hebrew terms: pala (wonderful/too hard), tsachaq (laugh), akedah (binding), Moriah, YHWH Yireh (the LORD will provide), and Makhpelah (double cave). |

| Visual learner? | The study guide charts map the typological parallels between the Akedah and the Atonement, and the geographic journey from Mamre to Moriah to Machpelah. |

| Following our Hebrew journey? | Big update! The Hebrew Language Journey section now has eight full lessons — from the Aleph-Bet all the way through Parts of Speech, with interactive charts, audio pronunciation guides, and IPA breakdowns. More details below. |

| Learn best by watching? | The Weekly Resources page has curated video commentaries with summaries to help you choose which to watch. From short overviews to scholarly deep dives, there's something for every schedule. |

| Teaching this week? | The Teaching Applications file has ready-to-use ideas for 7 contexts — personal study, Family Home Evening, Sunday School, Seminary/Institute, Relief Society/Elders Quorum, Primary, and Missionary Teaching. Each includes specific activities, discussion questions, and scripture selections. |

| Want study questions? | The Study Questions file has 200+ questions organized by category for individual reflection, group discussion, or journal prompts. |

If you've visited the new Hebrew Language Journey section, you may have noticed — it's grown! What started as a simple alphabet chart a few weeks ago has expanded into a full introductory curriculum. We now have eight lessons available, each building on the last:

| Lesson | Topic | What You'll Learn |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Aleph-Bet | All 22 consonants, their names, sounds, and how the script evolved from ancient pictographs |

| 2 | Pronunciation | How to actually say each letter, with audio examples and transliteration guides |

| 3 | IPA (Sound System) | The International Phonetic Alphabet — precise sound descriptions for every Hebrew consonant |

| 4 | How Sounds Are Made | Your mouth as an instrument — where and how each Hebrew sound is physically produced |

| 5 | Vowels & Nikud | The dot-and-dash system that gives Hebrew its vowels — how to read the marks beneath the letters |

| 6 | Dagesh & Letter Types | The little dot that changes everything — hard vs. soft letters, and how Hebrew classifies its consonants |

| 7 | The Root System | How three-letter roots form the backbone of Hebrew vocabulary — and why Jerusalem, shalom, and Solomon are all related |

| 8 | Parts of Speech | Nouns, verbs, prepositions — with a full parsing of Genesis 1:1 that reveals layers no English translation can show |

Each lesson includes written teaching content (not just charts), interactive visual aids, and cross-references to the others. They're designed to be warm and accessible — you don't need any background in Hebrew or linguistics. If you've ever been curious about the original language behind the scriptures you're reading each week, this is your on-ramp.

If you've been working through the lessons, you're already equipped to see things in this week's reading that most English readers miss. For example:

- Root system (Lesson 7): The root צ-ח-ק (tsachaq, "laugh") threads through the entire narrative — Abraham's laughter, Sarah's laughter, Isaac's very name (Yitschaq = "he laughs"), and Ishmael's mocking. Same three letters, different contexts, telling a story no translation can fully capture.

- Parts of speech (Lesson 8): When God asks "Is any thing too hard for the LORD?" the word translated "hard" is yippale from the root פ-ל-א (pala) — meaning wonderful, extraordinary, beyond human capacity. The same root gives us "Wonderful" in Isaiah 9:6. God wasn't asking if He was strong enough. He was asking if anything is too wonderful for the One whose name is Wonder.

- Root system (Lesson 7): Moriah carries two etymologies — from ר-א-ה (ra'ah, "to see/provide") and from moreh + Yah ("God teaches"). The place where Abraham offers Isaac is both the place where "the LORD will provide" and the place where "God teaches." Both are true.

You don't need the Hebrew lessons to study Genesis 18–23. But if you've been working through them, you'll find that the language itself is telling a richer story than any translation alone can deliver.

Now that we have the foundations in place — alphabet, sounds, vowels, roots, and parts of speech — the next lessons will start putting it all together. We'll be looking at how Hebrew verb stems (the binyanim) work, which is where the root system truly comes alive. You'll see how the same three-letter root can mean "to guard," "to be guarded," or "to cause someone to guard" just by changing its pattern. It's one of the most elegant features of Hebrew, and it's going to make passages like the Akedah even richer.

At your own pace. No rush. The lessons will be there when you're ready.

The scene at Mamre begins with hospitality so extravagant it became the Jewish paradigm for welcoming strangers. Abraham sees three visitors, runs to meet them, bows to the ground, prepares a feast of calf and cakes and curds. He stands while they eat — the host serving, not presiding. The rabbis would later call this hakhnasat orchim, the welcoming of guests, and rank it among the highest of all virtues.

But the hospitality is a frame for revelation. One of the visitors — identified as the LORD Himself — makes an announcement: "I will certainly return unto thee according to the time of life; and, lo, Sarah thy wife shall have a son" (Genesis 18:10).

Sarah, listening at the tent door, laughed within herself. "After I am waxed old shall I have pleasure, my lord being old also?" (Genesis 18:12). Her laughter is deeply human. She had waited twenty-five years since God first promised Abraham a son. She was ninety years old, well past the age of childbearing. She had watched her body refuse what her faith longed for. At some point, most of us learn to protect ourselves from hoping too much. Sarah's laughter was the sound of self-protection.

And God's response was not anger but astonishment: "Wherefore did Sarah laugh? ... Is any thing too hard for the LORD?" (Genesis 18:13-14).

The Hebrew word translated "hard" is yippale — from the root pala (פָּלָא), which means wonderful, extraordinary, surpassing human capacity. The same root gives us Pele in Isaiah 9:6: "His name shall be called Wonderful." When God asked Sarah, "Is anything too pala for Me?" He wasn't flexing divine muscle. He was saying: Is there any wonder too wonderful for the One whose very name is Wonder?

This question reverberates through the rest of scripture:

- Jeremiah, watching Jerusalem fall: "Behold, I am the LORD, the God of all flesh: is there any thing too hard for me?" (Jeremiah 32:27)

- The angel Gabriel to Mary: "For with God nothing shall be impossible" (Luke 1:37)

- Nephi, to his doubting brothers: "He is mighty to do all things for the children of men, if it so be that they exercise faith in him" (1 Nephi 7:12)

The pattern is always the same: God makes a promise that exceeds human capacity. Humans doubt. God delivers — not despite the impossibility, but through it, so that no one can mistake the source.

Abraham waited twenty-five years between God's first promise of a son (Genesis 12:2, when Abraham was 75) and Isaac's birth (Genesis 21:5, when Abraham was 100). Twenty-five years. That's not a brief trial. That's a quarter of a lifetime spent holding a promise that biology contradicted more with every passing year. And God's timing was deliberate — Isaac came when both parents were biologically incapable, making the miracle undeniable.

Hebrews 11:11 praises Sarah specifically: "Through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive seed, and was delivered of a child when she was past age, because she judged him faithful who had promised."

She judged Him faithful. Not because the evidence supported it. Not because the timeline made sense. But because she came to know the character of the One who promised.

What "impossible" promises has God made to you? A patriarchal blessing that seems wildly beyond your current trajectory? A temple sealing that binds you to people who feel unreachable? A promise of healing, or reunion, or peace that your circumstances flatly contradict? The question is not whether it's hard. The question is whether anything is too pala — too wonderful — for the God who names Himself Wonder.

Genesis 22 is one of the most carefully constructed narratives in all of literature. Every word bears weight. Every silence speaks.

"And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham" (Genesis 22:1). The Hebrew word for "tempt" here is nissah (נִסָּה) — better translated "tested" or "proved." God was not enticing Abraham to evil. He was revealing the depth of Abraham's faith — not to God, who already knew it, but to Abraham himself, and to every soul who would ever read this story.

"Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering" (Genesis 22:2).

Notice the agonizing precision: thy son — thine only son — Isaac — whom thou lovest. Four phrases, each narrowing the focus, each twisting the knife. God doesn't say "sacrifice a child." He names Isaac. He names the love. He makes sure Abraham cannot mistake what is being asked.

And Abraham's response? Silence. No protest. No negotiation. No "remember when I bargained You down to ten righteous in Sodom?" The man who argued for strangers says nothing when it's his own son. He rises early in the morning, saddles his donkey, and goes.

The journey takes three days. Three days of walking with the knowledge of what awaits. Three days — the same period Christ would spend in the tomb. Jewish tradition (Seder Olam) holds that Isaac was not a small child but a grown man of thirty-seven, making his participation willing. Whether or not we accept that specific age, the text strongly implies Isaac's cooperation: he carries the wood himself, and he does not resist when Abraham binds him.

Then comes the question that breaks the heart of every parent who has ever read it:

"My father... Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?" (Genesis 22:7)

And Abraham's answer — the most prophetic sentence in the Old Testament: "My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering" (Genesis 22:8).

God will provide himself a lamb. Read it both ways: God will provide for Himself a lamb, and God will provide Himself as the lamb. The ambiguity is the prophecy. On that same mountain range, two thousand years later, God would do exactly both.

The typological parallels are staggering, and the Book of Mormon confirms them explicitly. Jacob 4:5: "Abraham... offering up his son Isaac, which is a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son."

Consider the correspondences:

- Isaac is Abraham's "only son" (Gen. 22:2) — Christ is the Father's "Only Begotten" (John 3:16)

- Isaac carries the wood of his own sacrifice — Christ carries the cross

- The journey to Moriah takes three days — Christ rises on the third day

- Mount Moriah is traditionally the Temple Mount in Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 3:1) — Golgotha is just outside those walls

- A ram is caught in a thicket (thorns) and becomes the substitute — Christ wears a crown of thorns and becomes our substitute

- Abraham names the place YHWH Yireh — "The LORD will provide/see" (Genesis 22:14)

That name — YHWH Yireh — deserves its own moment. The Hebrew root ra'ah (ר-א-ה) means "to see," but in Hebrew, seeing and providing are linked. To see a need is to meet it. When Abraham declared "The LORD will see," he meant "The LORD will provide." And the text adds: "as it is said to this day, In the mount of the LORD it shall be seen" (Gen. 22:14). Future tense. Still pointing forward. Still waiting for the ultimate provision.

The Akedah is not just a story about obedience. It is the Old Testament's most intimate portrait of what it cost the Father to offer the Son. When we read Genesis 22, we are not simply watching Abraham's faith. We are watching a rehearsal — a living, breathing prophecy enacted in real time — of the event that would redeem the world.

D&C 132:36 adds the Restoration's witness: "Abraham was commanded to offer his son Isaac; nevertheless, it was written: Thou shalt not kill. Abraham, however, did not refuse, and it was accounted unto him for righteousness."

Abraham held two truths simultaneously: God's command to offer Isaac, and God's prohibition against killing. He did not resolve the contradiction. He walked into it, trusting that the God who gave both commands could reconcile them. That is what faith looks like at its most refined — not the absence of tension, but the willingness to walk forward within the tension, trusting the One who holds all things together.

In the midst of this week's grandest narratives — divine visitors, impossible births, the binding of Isaac — one of the most haunting moments comes in a single verse:

"But his wife looked back from behind him, and she became a pillar of salt." (Genesis 19:26)

One verse. No name given. No dialogue. Just a backward glance and a transformation into salt.

The Hebrew verb for "looked back" is vattabbet, from the root nabat (נ-ב-ט), which means to gaze intently, to look with focused attention or longing. This wasn't a casual glance over the shoulder. This was a woman fixing her gaze on what she'd been told to leave. The verb tells us her heart was still in Sodom even as her feet carried her away.

Jesus made this single verse into a sermon: "Remember Lot's wife" (Luke 17:32). Three words. The shortest sermon He ever preached, and one of the most piercing.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland gave this image its fullest modern expression: "She wasn't just looking back; she looked back longingly... Her attachment to the past outweighed her confidence in the future. It would not be the last time that the leaving of Sodom would be difficult for people."

The contrast in this week's reading is striking. Abraham consistently looks forward — forward to the promised son, forward to Moriah, forward to God's provision. In Genesis 22:13, "Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked [vayyar], and behold behind him a ram." He looked and saw provision. Lot's wife looked and saw only what she was losing.

Salt preserves — but it also renders barren. The Dead Sea region where this story takes place is rich in salt formations, including pillar-like structures along the shore that ancient travelers would have known well. The symbolism is layered: Lot's wife became a monument to preservation without life. She was preserved in the posture of her longing, frozen in the moment of her divided loyalty, standing forever at the threshold between deliverance and destruction.

What are our Sodoms? Not necessarily great sins — sometimes they're comfortable compromises, familiar mediocrity, relationships or habits we've been told to leave but can't stop gazing at longingly. The question isn't whether we've physically left. The question is where our eyes are fixed.

The angels' command to Lot's family was not just "leave" but "escape for thy life; look not behind thee, neither stay thou in all the plain" (Genesis 19:17). Don't look back. Don't linger. Don't negotiate with the thing God is delivering you from. The deliverance is total, or it isn't deliverance at all.

There is a thread of laughter woven through Genesis 17–21 that culminates in one of the most beautiful name-theology moments in all of scripture.

It begins with Abraham. When God told him — at ninety-nine years old — that Sarah would bear a son, "Abraham fell upon his face, and laughed" (Genesis 17:17). His laughter accompanied prostration — falling on his face before God. This was not mockery. It was the laughter of stunned wonder, the involuntary response to a promise so extravagant it overflowed the mind's capacity to hold it.

Then Sarah. Listening at the tent door as the divine visitor repeated the promise, "Sarah laughed within herself" (Genesis 18:12). Her laughter was interior, private, protective. She laughed within herself — the Hebrew emphasizes the inwardness of it. This was the laughter of someone who had stopped hoping aloud.

When confronted, Sarah denied it: "I laughed not." And the LORD said simply: "Nay; but thou didst laugh" (Genesis 18:15). He didn't condemn the laughter. He just named it. He saw her.

And then the fulfillment. Isaac is born. And his name — יִצְחָק (Yitschaq) — means "he laughs." Every single time anyone spoke Isaac's name, they were saying the word "laughter." The child's identity was the memory of what God had done with human doubt.

Sarah's response at Isaac's birth is one of the most joyful moments in the Old Testament: "God hath made me to laugh, so that all that hear will laugh with me" (Genesis 21:6). The Hebrew here uses an intensive form — this isn't a chuckle. This is covenant-sized, overflowing, infectious laughter. God made her laugh. He took her incredulous, self-protective, interior laughter and transformed it into something communal and celebratory. All who hear will laugh with her.

This is the emotional arc the root tsachaq traces across four chapters:

- Abraham's laughter (17:17) — stunned wonder

- Sarah's laughter (18:12) — self-protective doubt

- Isaac's name (21:3) — divine commemoration

- Sarah's laughter reborn (21:6) — transformed, communal joy

- Ishmael's laughter (21:9) — mocking, the shadow side

The same root. The same three letters. But the meaning transforms as the story unfolds — from disbelief to delight, from private doubt to public testimony. Isaac's name is a monument to the journey. Every time it's spoken, it says: God took what seemed laughable and made it the source of joy.

There is something profoundly reassuring in the fact that God didn't choose a name meaning "faith" or "obedience" for the child of promise. He chose laughter. He chose to memorialize the very doubt that preceded the miracle — not to shame Sarah, but to celebrate the transformation. The name says: Yes, you laughed. And now the laughter is real.

If you have ever laughed — not with joy but with the bitter, tired laughter of someone who has waited too long — Isaac's name is for you. God doesn't erase the doubt. He redeems it. He turns the laughter of "that's impossible" into the laughter of "look what God has done."

We should not leave this week without pausing at Genesis 23, which can feel anticlimactic after the drama of the Akedah but carries its own quiet theological weight.

Sarah dies at 127. Abraham mourns, weeps, and then does something remarkable: he negotiates, publicly and meticulously, for a burial plot. He approaches the Hittites at the city gate — the ancient equivalent of a courthouse. He asks to purchase the cave of Machpelah (מַכְפֵּלָה, "the double cave") from Ephron. The negotiation follows formal ANE legal customs: public witnesses, stated price, recorded transaction. Abraham pays 400 shekels of silver — likely an inflated price — without bargaining.

Why does this matter?

Because God had promised Abraham "all this land" (Genesis 13:15). And at the end of Abraham's life, the only land he legally owned was a burial cave. The man to whom God had said "all the land which thou seest, to thee will I give it" died owning nothing but a tomb.

And yet that tomb became the anchor of everything. Sarah was buried there. Then Abraham. Then Isaac and Rebekah. Then Jacob and Leah. The cave of Machpelah became the patriarchal burial site — the place where the family of the covenant was gathered, generation after generation, in death as in life.

The name itself — Makhpelah, from the root כ-פ-ל (K-P-L), "to double" — suggests a cave with two chambers. But the doubling resonates beyond architecture. This is a place where promise and patience are doubled: the promise of the land, and the patience to wait for its fulfillment. Abraham held the deed to a grave while believing in a kingdom. He planted his family in the earth of Canaan while trusting God for a celestial inheritance.

There is something deeply faithful about burying your dead in the land of promise when you haven't yet received the promise. It's an act of investment in a future you can't see. It says: We belong here. Not because we possess it, but because God said so.

For us, the Machpelah principle might look like temple sealings that bind us to people whose return we can't guarantee. Or callings we serve in faithfully when we can't see the fruit. Or covenants we keep in seasons when keeping them feels like owning a cave instead of a kingdom. The deed is small. The promise is not.

Week 09 Weekly Insights | CFM Corner | OT 2026

Created: February 19, 2026

Week 9

Genesis 18–23

| Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Week | 09 |

| Dates | February 23 – March 1, 2026 |

| Reading | Genesis 18–23 |

| CFM Manual | Genesis 18–23 Lesson |

| Total Chapters | 6 (Genesis 18–23) |

| Approximate Verses | ~145 verses |

This week contains some of the most dramatic and theologically profound narratives in all of scripture: the theophany at Mamre where God and two angels visit Abraham, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, the long-awaited birth of Isaac, the harrowing test of the Akedah (binding of Isaac), and Sarah's death and burial at Machpelah. Each story reveals dimensions of faith, covenant, divine mercy, and sacrifice.

Genesis 18 opens with three mysterious visitors at Abraham's tent near the oaks of Mamre. Abraham, recognizing the divine nature of at least one visitor, offers hospitality. The LORD announces that Sarah will bear a son within the year. Sarah, listening from the tent, laughs at the impossibility—she is 90 years old and "past the age of women." The LORD's response becomes the theme of this week: "Is any thing too hard for the LORD?" (Genesis 18:14). The chapter concludes with Abraham interceding for Sodom, negotiating with God to spare the city if even ten righteous people can be found.

Genesis 19 narrates Sodom's destruction. Two angels arrive at Sodom's gates, where Lot offers them hospitality. The men of Sodom surround Lot's house, demanding the visitors. The angels strike the mob with blindness and urge Lot's family to flee. Lot, his wife, and two daughters escape as fire and brimstone rain from heaven. But Lot's wife "looked back" and became "a pillar of salt" (Genesis 19:26)—a haunting warning about divided loyalties.

Genesis 21 records the fulfillment of God's promise: Isaac is born when Abraham is 100 and Sarah 90. The name Isaac (יִצְחָק, Yitschaq) means "he laughs," commemorating Sarah's laughter and God's joy in fulfilling the impossible. But tension arises between Sarah and Hagar; Abraham reluctantly sends Hagar and Ishmael away. God hears Hagar's cry and promises to make Ishmael a great nation.

Genesis 22 presents the ultimate test: "Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering" (Genesis 22:2). Abraham obeys without recorded protest. On the third day, they arrive at Moriah. Isaac carries the wood; Abraham carries the fire and knife. Isaac asks, "Where is the lamb?" Abraham responds with prophetic faith: "God will provide himself a lamb" (Genesis 22:8). As Abraham raises the knife, the Angel of the LORD intervenes. A ram caught in a thicket becomes the substitute. This narrative—the Akedah—is the supreme type of the Atonement, foreshadowing the Father's offering of His Only Begotten Son.

Genesis 23 closes with Sarah's death at age 127. Abraham purchases the cave of Machpelah from Ephron the Hittite—the first land Abraham legally owns in Canaan. The meticulous transaction confirms the covenant promise of land. Sarah is buried there, followed eventually by Abraham, Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, and Leah—making Machpelah the patriarchal burial site.

Theme 1: "Is Any Thing Too Hard for the LORD?"

When the LORD announced that Sarah would bear a son, she laughed. God's response—"Is any thing too hard for the LORD?"—is rhetorical: the Hebrew pala (פָּלָא) means "wonderful, difficult, extraordinary." Nothing is too wondrous for God.

This question echoes through scripture:

- Jeremiah 32:27: "Behold, I am the LORD, the God of all flesh: is there any thing too hard for me?"

- Luke 1:37: "With God nothing shall be impossible"

Application: What "impossible" promises has God made to you? Patriarchal blessings? Temple sealings? Eternal increase? Will you trust Him despite natural impossibility?

Theme 2: The Akedah—Father and Son

Genesis 22 is the Akedah (עֲקֵדָה, "the binding")—the supreme OT type of the Atonement. Every detail foreshadows Christ:

- Isaac is Abraham's "only son" (Genesis 22:2) / Christ is the "Only Begotten" (John 3:16)

- Isaac carries the wood / Christ carries the cross

- Mount Moriah (Jerusalem) / Golgotha

- Three-day journey / Three days in the tomb

- Abraham's willingness to sacrifice / Father's sacrifice of Son

- The ram substitutes for Isaac / Christ substitutes for us

Jacob 4:5 confirms: "Abraham... offering up his son Isaac, which is a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son."

Theme 3: Looking Back vs. Looking Forward

Lot's wife "looked back" and became a pillar of salt. Jesus warned: "Remember Lot's wife" (Luke 17:32). Elder Jeffrey R. Holland taught: "She wasn't just looking back; she looked back longingly... Her attachment to the past outweighed her confidence in the future."

Application: What Sodoms are we reluctant to leave? What sins, relationships, or worldly attachments do we "look back" to longingly?

Theme 4: God's Promises Fulfilled in His Time

Abraham waited 25 years from the initial promise (Gen. 12:2; age 75) to Isaac's birth (Gen. 21:5; age 100). The delay tested faith. Yet God's timing was perfect—Isaac came when both Abraham and Sarah were biologically incapable, making the miracle undeniable.

Hebrews 11:11 praises Sarah: "Through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive seed, and was delivered of a child when she was past age, because she judged him faithful who had promised."

Theme 5: Abraham's Intercession

Genesis 18:23–33 records Abraham's bold intercession for Sodom: "Wilt thou destroy the righteous with the wicked?" Abraham negotiates with God—fifty righteous, then forty-five, forty, thirty, twenty, finally ten. God agrees to spare Sodom for ten righteous. None are found.

This establishes the principle that the righteous can intercede for the wicked, delaying judgment. It foreshadows Christ, the ultimate Intercessor (Hebrews 7:25).

| Person | Role | Significance This Week |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham | Patriarch, Prophet | Intercedes for Sodom; offers Isaac; purchases Machpelah |

| Sarah | Matriarch | Laughs at promise; bears Isaac at 90; dies at 127 |

| Isaac | Promised son | Born miraculously; bound on Mount Moriah; type of Christ |

| Lot | Abraham's nephew | Escapes Sodom; his wife becomes pillar of salt |

| Lot's wife | Warning example | Looks back longingly; becomes salt |

| Hagar & Ishmael | Abraham's firstborn | Sent away; God hears Ishmael in wilderness |

| The LORD & two angels | Divine visitors | Announce Isaac; destroy Sodom; test Abraham |

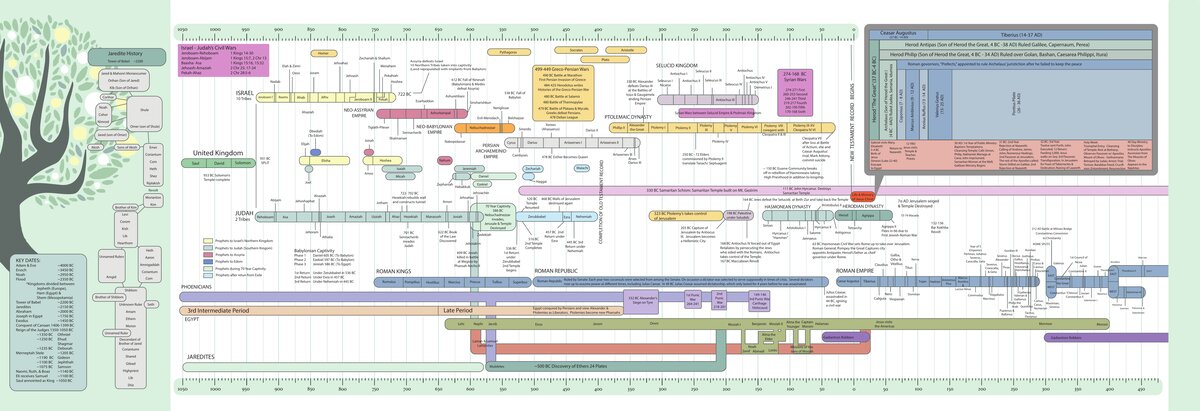

Historical Period: Middle Bronze Age / Patriarchal Period

Approximate Dates: ~1900–1850 BC

Abraham's Age: 99–100 (Isaac's birth); ~137 (Akedah if Isaac ~37); ~137 (Sarah's death)

Relationship to Previous/Next Weeks

Week 08: Abrahamic covenant established (Gen. 12–17)

Week 09: Covenant tested and Isaac born (Gen. 18–23)

Week 10: Covenant continues through Isaac and Jacob (Gen. 24–33)

Book of Mormon Connections

- Jacob 4:5: "Abraham... offering up his son Isaac, which is a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son"

- Helaman 8:16–17: Abraham "raised his eyes towards heaven, and sought redemption of Christ"

Doctrine and Covenants Connections

- D&C 132:36: "Abraham was commanded to offer his son Isaac; nevertheless, it was written: Thou shalt not kill. Abraham, however, did not refuse, and it was accounted unto him for righteousness"

- Divine Omnipotence: Nothing is too hard for God (Gen. 18:14)

- Christ as Sacrifice: The Akedah prefigures the Atonement (Gen. 22; Jacob 4:5)

- Intercession: Abraham intercedes for Sodom; Christ intercedes for us (Gen. 18:23–33; Heb. 7:25)

- Fleeing Wickedness: Lot's wife warns against looking back (Gen. 19:26; Luke 17:32)

- Covenant Land: Abraham purchases Machpelah (Gen. 23)

- Mount Moriah: Tradition identifies this as the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Abraham's sacrifice foreshadows temple ordinances centered on Christ's sacrifice.

- Substitutionary Atonement: The ram substitutes for Isaac; Christ substitutes for us.

- Covenant Names: Isaac ("laughter") reflects covenant joy; name changes signal identity transformation.

Manual Focus: Trusting God's promises in His time; fleeing wickedness without looking back; Abraham's sacrifice as similitude of Father and Son.

Key Questions from Manual:

- Is any thing too hard for the LORD?

- How do we sustain faith when promised blessings are delayed?

- What does "looking back" mean in our spiritual journey?

- How is Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac a similitude of God and Christ?

Essential Reading:

- Genesis 18:9–14 — "Is any thing too hard?"

- Genesis 19:12–29 — Sodom's destruction; Lot's wife

- Genesis 21:1–7 — Isaac's birth

- Genesis 22:1–19 — The Akedah

For Deep Study:

- Genesis 18:16–33 — Abraham's intercession

- Genesis 23 — Purchase of Machpelah

Week 9 (2022 Lesson 8): Abraham's Hebron: Then and Now (Five-part series)

- KnoWhy OTL08A-E: Multi-part exploration of Abraham's connections to Hebron/Machpelah

| File | Content Focus |

|---|---|

| 01_Week_Overview | This overview document |

| 02_Historical_Cultural_Context | ANE context, Sodom archaeology, burial customs |

| 03_Key_Passages_Study | Detailed analysis: Gen. 18:14; 19:26; 21:1-7; 22:1-19 |

| 04_Word_Studies | Hebrew: pala, tsachaq, akedah, Moriah |

| 05_Teaching_Applications | Teaching the Akedah, Lot's wife, impossible promises |

| 06_Study_Questions | 200+ questions for study |

Week 09 Study Guide | CFM Corner | OT 2026

File Status: Complete

Created: January 20, 2026

Last Updated: January 20, 2026

Next File: 02_Historical_Cultural_Context.md

The Oaks of Mamre (Genesis 18)

Abraham's encampment at Mamre (modern Hebron area) placed him at a major crossroads in the central hill country of Canaan. Sacred trees were common gathering and worship sites throughout the ANE. The terebinth or oak grove at Mamre became associated with divine encounter — the rabbis later called this theophany "the hospitality of Abraham" (hakhnasat orchim), elevating hospitality to one of the highest virtues.

Hospitality in the Ancient World

Abraham's elaborate welcome — running to greet strangers, bowing to the ground, washing feet, preparing a calf, standing while they ate — reflects ANE hospitality codes that were deeply embedded cultural obligations. Refusing hospitality or violating the host-guest relationship was considered one of the gravest social sins. This contrasts sharply with Sodom's treatment of visitors in Genesis 19.

Sodom and Gomorrah: Archaeological Context

The Cities of the Plain have been associated with several archaeological sites near the Dead Sea:

- Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira — Early Bronze Age sites in the southeastern Dead Sea region that show evidence of sudden, catastrophic destruction by fire (~2350 BC)

- Tall el-Hammam — A large Bronze Age city northeast of the Dead Sea, proposed by some archaeologists (Steven Collins) as biblical Sodom. A 2021 study in Scientific Reports documented evidence of a cosmic airburst event (~1650 BC) that destroyed the city with extreme heat

- The Dead Sea region itself shows geological evidence of bitumen, sulfur, and seismic activity consistent with the biblical description of "brimstone and fire" (Gen. 19:24)

Lot's Wife and Salt

The Dead Sea region is rich in salt formations, including pillar-like formations along the southwestern shore. Josephus (Antiquities 1.11.4) claimed the pillar was still visible in his day. The transformation likely carries symbolic weight: salt preserves but also renders barren. Looking back to Sodom meant being claimed by its destruction.

The Akedah: Restoring the Meaning of Sacrifice

To modern readers, God's command to Abraham in Genesis 22 can feel shocking — even disturbing. But to understand what God was doing, we need to see the world Abraham lived in.

Human sacrifice was not uncommon in the ancient Near East. Archaeological evidence from Mesopotamia, Canaan, and surrounding cultures reveals a disturbing pattern: children were offered to deities like Molech, Chemosh, and others as the ultimate act of devotion. Abraham knew this world intimately. According to the Book of Abraham (Abraham 1:5–12), his own father Terah participated in this practice — Abraham himself was nearly sacrificed on an altar in Ur by a priest of Pharaoh. He had witnessed firsthand the corruption of something sacred into something monstrous.

The original covenant of sacrifice — established from the days of Adam — was meant to point forward to the sacrifice of the Son of God. It was a teaching ordinance, a way for God's children to understand that a Redeemer would come who would offer Himself on their behalf. But by Abraham's day, that understanding had been catastrophically distorted. Instead of a symbolic offering pointing to God's future gift, sacrifice had become a way for humans to appease angry gods by offering their most precious possessions — including their own children. The covenant had been turned on its head: instead of God giving His Son for humanity, humanity was giving its sons to idols.

This is what God abhorred. "They have built also the high places of Baal, to burn their sons with fire for burnt offerings unto Baal, which I commanded not, nor spake it, neither came it into my mind" (Jeremiah 19:5). The practice was not just wrong — it was the precise inversion of the truth that sacrifice was designed to teach.

The Akedah, then, was not God testing Abraham's willingness to do what the pagans did. It was God restoring Abraham's understanding of what sacrifice actually meant. Abraham walked up Moriah carrying the assumptions of his world — that the gods demand the blood of sons. He walked down having learned the truth: that God Himself would provide the lamb. The ram in the thicket was not just a last-minute rescue. It was the lesson. God was saying: I do not want your son. I never wanted your children. I will provide My own Son. The entire Akedah was a correction — a recalibration of the covenant of sacrifice from its corrupted form back to its original, prophetic purpose.

This is why Abraham named the place "The LORD will provide" — future tense, pointing forward to Calvary. And this is why the angel's response was not "well done for being willing to kill" but rather a reaffirmation of the covenant blessings (Genesis 22:16–18). Abraham had not just passed a test. He had been taught the deepest truth of the gospel: that God so loved the world that He would give His Only Begotten Son.

The Akedah in Jewish and Christian Tradition

The binding of Isaac (Genesis 22) is arguably the most interpreted passage in the entire Hebrew Bible:

- Jewish tradition (Midrash): Isaac was not a child but a grown man (37 years old per Seder Olam), who willingly offered himself. Some midrashim suggest Isaac actually died and was resurrected.

- Islamic tradition: The Quran (37:100–111) tells a similar story but traditionally identifies Ishmael as the one offered.

- Christian typology: From the earliest church fathers, the Akedah was read as the supreme Old Testament type of the Crucifixion (cf. Jacob 4:5).

Mount Moriah

The Hebrew Moriyyah (מוֹרִיָּה) carries layered meaning. It may derive from ra'ah (רָאָה, "to see") — hence Abraham named it "The LORD will see/provide" (Genesis 22:14). But there is a second etymology equally significant: moreh (מוֹרֶה, "teacher, one who instructs") combined with Yah (יָהּ, the divine name) — giving us "the teaching of God" or "God is my teacher." The word moreh comes from the root י-ר-ה (Y-R-H), meaning "to direct, point the way, instruct" — the same root that gives us Torah (תּוֹרָה, "instruction, teaching"). Moriah is, at its root level, the mountain of God's Torah — the place of divine instruction. On this mountain, God both provides and instructs. Abraham came to offer — and left having been taught the deepest lesson of the covenant: that God Himself would provide the Lamb. 2 Chronicles 3:1 explicitly identifies Moriah as the site of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem — the place where God's people would come, generation after generation, to both see Him and be taught by Him. The mountain of sacrifice became the mountain of instruction.

Cave of Machpelah (Genesis 23)

Abraham's purchase of the Cave of Machpelah from Ephron the Hittite follows a recognizable ANE legal transaction pattern:

- Public negotiation at the city gate (the ancient courthouse)

- Witnesses present

- Price stated and weighed (400 shekels of silver "current money with the merchant")

- Both land and trees included in the deed

The Hittite land sale customs recorded in cuneiform tablets from Hattusa show similar patterns. This was Abraham's first legal land ownership in Canaan — significant because the entire land had been promised to his descendants.

Today, the Cave of Machpelah (Hebron) is enclosed by a massive Herodian structure and remains one of the most sacred sites in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Hagar and Ishmael (Genesis 21:8–21)

The expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael reflects ANE inheritance customs. With Isaac's birth, Ishmael's status as heir was threatened. Sarah's demand aligns with laws known from Nuzi tablets, where a handmaid's son could be disinherited once a legitimate heir was born. God's promise to Hagar — "I will make him a great nation" (Gen. 21:18) — ensures divine care beyond the covenant line.

| Term | Meaning | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Theophany | Divine appearance | God appears to Abraham at Mamre (Gen. 18) |

| Akedah (עֲקֵדָה) | "Binding" | The binding of Isaac; supreme test of faith |

| Machpelah (מַכְפֵּלָה) | "Double (cave)" | Patriarchal burial site; first land purchased |

| Moriah (מוֹרִיָּה) | "Seen by the LORD" | Site of sacrifice; later Temple Mount |

| Hakhnasat Orchim | Hospitality to guests | Abraham's supreme example (Gen. 18:1–8) |

Key Locations This Week

- Mamre/Hebron — Abraham's encampment; Sarah's burial (Gen. 18, 23)

- Sodom & Gomorrah — Cities of the Plain; destroyed (Gen. 19)

- Zoar — City Lot flees to (Gen. 19:22)

- Beersheba — Abraham plants a grove; calls on God (Gen. 21:33)

- Mount Moriah — The Akedah; later Temple Mount (Gen. 22:2)

Week 09 Study Guide | CFM Corner | OT 2026

File Status: Complete

Created: 2026-02-18

Text Focus: Genesis 18:9–14

And they said unto him, Where is Sarah thy wife? And he said, Behold, in the tent. And he said, I will certainly return unto thee according to the time of life; and, lo, Sarah thy wife shall have a son. And Sarah heard it in the tent door, which was behind him... Therefore Sarah laughed within herself, saying, After I am old shall I have pleasure, my lord being old also? And the LORD said unto Abraham, Wherefore did Sarah laugh?... Is any thing too hard for the LORD?

Analysis

- Three visitors — one of them is YHWH: This is not inference; the text itself makes the identification. Genesis 18:1 opens by stating "the LORD (יהוה) appeared unto him in the plains of Mamre" — before Abraham even looks up to see three men. The narrative then shifts between plural and singular: "they said" (v. 9) when all three speak, but "he said" (וַיֹּאמֶר, singular, v. 10) when the promise of Isaac is announced, and "the LORD said" (v. 13) when Sarah's laughter is confronted. The grammar distinguishes one visitor from the other two. Later, Genesis 19:1 confirms the distinction: only two angels arrive at Sodom — the third, identified as YHWH, stayed behind with Abraham for the intercession dialogue (18:22–33). The text uses both the narrator's voice and Hebrew grammar to make this identification explicit.

- "According to the time of life" (כָּעֵת חַיָּה, ka'et chayyah): Literally "at the time of reviving/living" — probably meaning "this time next year when life comes around again."

- Sarah's laughter is not mocking but incredulous — the impossible has become personal. Her laughter (tsachaq) gives Isaac his name.

- "Is any thing too hard for the LORD?" (Genesis 18:14) — The Hebrew reads הֲיִפָּלֵא מֵיְהוָה דָּבָר (hayippale me-YHWH davar). The verb יִפָּלֵא (yippale) is from the root פ-ל-א (pala), meaning "wonderful, extraordinary, surpassing human capacity" — the same root that gives us Pele ("Wonderful") in Isaiah 9:6. The KJV's "hard" undersells it. God is not asking "is this too difficult?" — He is asking "is there any wonder too wonderful for Me?" This is not a rebuke but an invitation to awe.

Cross-References

- Jeremiah 32:17, 27 — "There is nothing too hard for thee"

- Luke 1:37 — "With God nothing shall be impossible" (Gabriel to Mary — another miraculous birth announcement)

- Romans 4:19–21 — Paul praises Abraham for not staggering at the promise

Prophetic Witness

"Had not Jesus, as Jehovah, said to Abraham, 'Is any thing too hard for the Lord?' (Gen. 18:14). Had not His angel told a perplexed Mary, 'For with God nothing shall be impossible'?"

— Neal A. Maxwell, "Willing to Submit", April 1985 General Conference

This connects pala directly to the Atonement — the same God who promised Sarah the impossible would Himself accomplish the most impossible wonder of all.

Spencer W. Kimball, "The Rewards, the Blessings, the Promises", October 1973 General Conference — quotes Genesis 18:14 and Sarah's laughter directly, affirming that God's promises transcend natural limitations.

Text Focus

Then the LORD rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the LORD out of heaven; And he overthrew those cities, and all the plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground. But his wife looked back from behind him, and she became a pillar of salt.

Analysis

- "Looked back" (וַתַּבֵּט, vattabbet): The verb nabat means more than a casual glance — it implies gazing intently, looking with longing or attention. She didn't just turn her head; she fixed her gaze on what she was leaving.

- "From behind him": She was lagging behind Lot, physically and spiritually.

- "Pillar of salt": Salt formations are common in the Dead Sea region. Symbolically, salt preserves the old — she was preserved in the posture of looking back.

- Jesus cited this as a warning (Luke 17:32): "Remember Lot's wife." In the context of His Second Coming, He warns against attachment to temporal things.

Cross-References

- Luke 9:62 — "No man, having put his hand to the plough, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God"

- Philippians 3:13–14 — "Forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth"

- Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, "The Best Is Yet to Be" (Jan 2010 Ensign): "She was not just looking back; in her heart she wanted to go back."

Prophetic Witness

"It is not possible for you to sink lower than the infinite light of Christ's Atonement shines... Don't you buy some second-rate scheme that the best way to face the future is to keep looking back."

— Jeffrey R. Holland, "Remember Lot's Wife", January 2009 BYU Devotional

This is THE definitive modern treatment of Lot's wife — Holland reframes her not as a minor character but as a universal warning about letting attachment to the past outweigh confidence in the future.

"The Lord was willing to spare Sodom and Gomorrah if Abraham could find just ten good men, which he could not do."

— Hartman Rector Jr., "Endure to the End in Charity", October 1994 General Conference

Text Focus

And the LORD visited Sarah as he had said, and the LORD did unto Sarah as he had spoken. For Sarah conceived, and bare Abraham a son in his old age, at the set time of which God had spoken to him. And Abraham called the name of his son that was born unto him... Isaac.

Analysis

- "The LORD visited" (פָּקַד, paqad): This verb carries weight — it means God intervened, attended to, fulfilled His promise. The same word is used when God "visits" Israel in Egypt (Exodus 3:16).

- "At the set time" (לַמּוֹעֵד, lamo'ed): This is the word mo'ed — "appointed time" — the exact same word used for Israel's festival calendar, the moedim (מוֹעֲדִים) of Leviticus 23. God's timing is not just precise — it is liturgical. Jewish tradition (Talmud, Rosh Hashanah 11a) connects Isaac's birth to Passover (Pesach), the feast of deliverance and new life. The Akedah is connected to Rosh Hashanah — the Torah reading for the second day of Rosh Hashanah is Genesis 22, and the shofar blown on that holy day is a ram's horn, commemorating the ram caught in the thicket that replaced Isaac. The pattern is striking: Isaac's birth at the mo'ed of Passover points to the Lamb who brings deliverance; Isaac's binding at the mo'ed of Rosh Hashanah points to the day of judgment and substitutionary sacrifice. Both feasts find their ultimate fulfillment in Christ.

- Abraham was 100, Sarah 90. The impossibility was the point — the miracle must be undeniably God's.

- Sarah's response (v. 6): "God hath made me to laugh, and all that hear will laugh with me." The laughter has transformed from incredulity to joy.

Cross-References

- Hebrews 11:11 — "Through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive seed... because she judged him faithful who had promised"

- Galatians 4:22–28 — Paul's allegory: Isaac = children of promise; Ishmael = children of the flesh

Prophetic Witness

Spencer W. Kimball, "The Rewards, the Blessings, the Promises", October 1973 General Conference — quotes Genesis 18:12 and Sarah's laughter directly, testifying that God's covenant promises are fulfilled in His own time, transforming doubt into joy.

Text Focus: Genesis 22:1–2, 7–8, 11–14

God did tempt [test] Abraham, and said... Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of.

And Isaac spake... My father... Behold the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt offering? And Abraham said, My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt offering.

And the angel of the LORD called unto him out of heaven... Lay not thine hand upon the lad... for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me.

Analysis

- "Tempt" (נִסָּה, nissah): Better translated "tested." God doesn't tempt to sin but tests to strengthen. The same root gives us nes (נֵס), "banner" — the test becomes a standard, a visible declaration of faith.

- "Thine only son" (יְחִידְךָ, yechidekha): "Only" here is yachid — unique, beloved, singular. The LXX translates this agapetos — the same word used of Jesus at His baptism: "This is my beloved [agapetos] Son" (Matthew 3:17).

- "God will provide himself a lamb": The Hebrew is ambiguous — it could mean "God will provide for Himself a lamb" or "God will provide Himself [as] the lamb." Both readings are theologically profound.

- Moriah → Temple Mount → Golgotha: The geography connects Abraham's sacrifice to the Temple to the Cross.

- "On the third day" (v. 4): Abraham received Isaac back "as from the dead" on the third day (cf. Hebrews 11:19).

Restoration Insight

- Jacob 4:5: "Abraham... offering up his son Isaac, which is a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son"

- D&C 132:36: "Abraham was commanded to offer his son Isaac; nevertheless, it was written: Thou shalt not kill. Abraham, however, did not refuse, and it was accounted unto him for righteousness"

Cross-References

- Hebrews 11:17–19 — "Accounting that God was able to raise him up, even from the dead; from whence also he received him in a figure"

- John 3:16 — "God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son"

- Romans 8:32 — "He that spared not his own Son, but delivered him up for us all"

Prophetic Witness

"A soul-stirring account of obedience is that of Abraham and Isaac... Untold generations have been blessed as a result."

— Thomas S. Monson, "Obedience Brings Blessings", April 2013 General Conference

"Abraham, who led Isaac on that heartbreaking journey to Mount Moriah, was faithfully going where the Lord wanted him to go."

— Dallin H. Oaks, "I'll Go Where You Want Me to Go", October 2002 General Conference

"Each time I walk with Abraham and Isaac on the road to Mount Moriah, I weep, knowing that Abraham does not know that there will be an angel and a ram in the thicket..."

— Susan W. Tanner, "My Soul Delighteth in the Things of the Lord", April 2008 General Conference

"There was no visible ram in the thicket when Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac."

— Thomas S. Monson, "The Call to Serve", October 2000 General Conference

Text Focus

And Abraham drew near, and said, Wilt thou also destroy the righteous with the wicked?... Peradventure there be fifty righteous within the city... And the LORD said, If I find in Sodom fifty righteous within the city, then I will spare all the place for their sakes.

Analysis

- Abraham negotiates: 50 → 45 → 40 → 30 → 20 → 10. Each time God agrees. Abraham stops at 10 — not because God would have refused less, but because Abraham stopped asking.

- The principle: The righteous can intercede for the wicked. A few faithful people can preserve an entire community.

- "Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?" (v. 25): Abraham appeals to God's justice — a remarkable moment where a human challenges God and God honors the challenge.

- This passage establishes the theological foundation for intercessory prayer.

Cross-References

- Hebrews 7:25 — Christ "ever liveth to make intercession for them"

- Moses 7:28 — Enoch sees God weep over the wicked

- Alma 34:15–16 — The great and last sacrifice

Prophetic Witness

"The Lord was willing to spare Sodom and Gomorrah if Abraham could find just ten good men, which he could not do."

— Hartman Rector Jr., "Endure to the End in Charity", October 1994 General Conference

Week 09 Study Guide | CFM Corner | OT 2026

File Status: Complete

Created: 2026-02-18

Root: פ-ל-א (P-L-A)

Appears: Genesis 18:14 — "Is any thing too hard [yippale] for the LORD?"

Meaning

The root pala doesn't primarily mean "difficult" in the modern sense. It means extraordinary, beyond human capacity, wonderful, surpassing. When God asks "Is anything too pala for Me?" He's asking: "Is there anything too wonderful for Me to accomplish?"

Related Forms

| Form | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| פֶּלֶא (pele) | Wonder, miracle | Isaiah 9:6 — "His name shall be called Wonderful [Pele]" |

| נִפְלָאוֹת (nifla'ot) | Wondrous deeds | Psalm 136:4 — "who alone doeth great wonders" |

| מַפְלִיא (mafli) | One who does wonders | Judges 13:19 — The angel "did wondrously" |

Theological Significance

This word is almost exclusively used of God's actions — miracles, acts of deliverance, creation. When applied to God, pala affirms omnipotence. The rhetorical question in Genesis 18:14 expects the answer: "Nothing."

LDS Application

- 1 Nephi 7:12: "He is mighty to do all things for the children of men, if it so be that they exercise faith in him"

- Moroni 7:33: "If ye will have faith in me ye shall have power to do whatsoever thing is expedient in me"

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | θαυμαστός (thaumastos) | wonderful, marvelous | Psalm 118:23 (LXX 117:23) |

| Latin (Vulgate) | mirabilis | wonderful, marvelous | Gen 18:14 |

| English | miracle (1828), marvel (1828) | From Latin miraculum (from mirari "to wonder") and mirabilia | — |

Root: צ-ח-ק (Ts-Ch-Q)

Appears: Genesis 18:12 (Sarah laughed); 21:3, 6 (Isaac's name); 21:9 (Ishmael "mocking")

Meaning

The root tsachaq covers a range: laugh, rejoice, jest, mock, play. The context determines the tone — joyful laughter, nervous laughter, or mocking laughter.

Key Occurrences in Genesis 18–21

| Verse | Who | Form | Tone |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17:17 | Abraham | וַיִּצְחָק | Joyful wonder (he fell on his face) |

| 18:12 | Sarah | וַתִּצְחַק | Incredulous / nervous |

| 21:3 | Name | יִצְחָק (Yitschaq) | "He laughs" — commemorative |

| 21:6 | Sarah | צְחֹק | "God has made me to laugh" — transformed joy |

| 21:9 | Ishmael | מְצַחֵק | "Mocking" / "playing" — negative connotation |

Theological Significance

Isaac's name encodes the entire emotional arc: incredulity → faith → fulfillment → joy. Every time the name "Isaac" is spoken, it recalls that God turns impossible laughter into covenant joy.

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | γελάω (gelaō) | to laugh | LXX Gen 18:12 |

| Latin (Vulgate) | rideo | to laugh | Vulgate Gen 18:12 ("risit") |

| English | risible (1828), gelastic (1828), ridiculous (1828) | From Latin risibilis, Greek gelaō, and Latin ridiculus | — |

Root: ע-ק-ד (Ayin-Q-D)

Appears: Genesis 22:9 — "and bound [va-ya'aqod] Isaac his son"

Meaning

The verb aqad means to bind, tie up — specifically binding the limbs. It appears only here in the entire Hebrew Bible in reference to binding a person. The noun akedah became the standard Jewish name for the entire episode.

Why "Binding" and Not "Sacrifice"?

Jewish tradition emphasizes that Isaac was bound but not sacrificed. The Akedah tests willingness, not completion. This is theologically critical:

- For Judaism: God does not desire human sacrifice; the test was of faith, not blood

- For Christianity: The incomplete sacrifice of Isaac points to the complete sacrifice of Christ — the one who was offered

- For Latter-day Saints: D&C 132:36 emphasizes Abraham's willingness despite the commandment "Thou shalt not kill"

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | δέω (deō) | to bind | General Greek (no direct LXX equivalent for aqad) |

| Latin (Vulgate) | ligo/ligare | to bind | Vulgate Gen 22:9 ("ligasset") |

| English | ligature (1828), ligament (1828), religion (1828), obligation (1828) | From Latin ligare; "religion" possibly from re-ligare "to re-bind" | — |

Root: Possibly from ר-א-ה (R-A-H, "to see") or י-ר-א (Y-R-A, "to fear/revere")

Appears: Genesis 22:2, 14

Meaning

The etymology is debated:

- **From ra'ah (to see):** "The place where the LORD is seen" or "The LORD will see/provide" — matching Abraham's declaration in 22:14: YHWH Yireh ("The LORD will see/provide")

- **From yare (to fear/revere):** "The place of reverence/awe"

- **From yarah (to teach):** "The place of instruction" (used in later Jewish tradition)

Connection to the Temple

2 Chronicles 3:1: "Then Solomon began to build the house of the LORD at Jerusalem in mount Moriah, where the LORD appeared unto David his father."

This makes Moriah one of the most layered sites in scripture:

- Abraham offered Isaac here (~1900 BC)

- David purchased the threshing floor (~1000 BC)

- Solomon built the Temple (~960 BC)

- Jesus was crucified nearby (~AD 33)

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | Μωριά (Mōria); also τὴν ὑψηλήν (tēn hypsēlēn) | transliteration; "the high/lofty land" | LXX 2 Chron 3:1; some LXX MSS of Gen 22:2 |

| Latin (Vulgate) | Moria | transliteration | Vulgate Gen 22:2 |

| English | provision (1828) | From Latin pro-videre "to see ahead" — matching ra'ah/yireh | — |

Root: ר-א-ה (R-A-H, "to see")

Appears: Genesis 22:14

Meaning

Abraham named the place YHWH Yireh — literally "The LORD will see." In Hebrew, "seeing" and "providing" are linked: to see a need is to provide for it. The KJV translates this as "the LORD will provide," but the Hebrew carries both meanings simultaneously.

The Double Fulfillment

- Immediate: God "saw" / provided the ram caught in the thicket

- Ultimate: God would "see" / provide His own Son as the sacrifice on this same mountain

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | κύριος εἶδεν (kyrios eiden); also πρόνοια (pronoia) | "the Lord saw"; provision, foresight | LXX Gen 22:14 |

| Latin (Vulgate) | Dominus videt; providentia | "the Lord sees"; foresight, provision | Vulgate Gen 22:14 |

| English | provide (1828), providence (1828), provision (1828), video (1828) | All from Latin pro-videre "to see ahead"; video = Latin "I see" | — |

Root: כ-פ-ל (K-P-L, "to double, fold")

Appears: Genesis 23:9, 17, 19

Meaning

Makhpelah means "the double one" — likely describing a cave with two chambers or a double-layered cave. Abraham purchased it as Sarah's burial place, and it became the family tomb for the patriarchs and matriarchs:

- Sarah (Gen. 23:19)

- Abraham (Gen. 25:9)

- Isaac and Rebekah (Gen. 49:31)

- Jacob and Leah (Gen. 49:31; 50:13)

Significance

This is the first land purchase in the covenant narrative. Though God promised Abraham "all this land," he owned none of it during his lifetime — except this burial cave. It became the anchor point for the land promise, the deed of trust that Abraham's descendants would inherit Canaan.

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | τὸ σπήλαιον τὸ διπλοῦν (to spēlaion to diploun) | the double cave | LXX Gen 23:9 |

| Latin (Vulgate) | spelunca duplex | double cave | Vulgate Gen 23:9 |

| English | diploma (1828), duplicate (1828), spelunking (1828) | From Greek diploun "double, folded" and Latin spelunca "cave" | — |

Root: נ-ב-ט (N-B-T)

Appears: Genesis 19:26 — "But his wife looked back [vattabbet]"

Meaning

Nabat means to look intently, gaze with attention or longing. It implies focused, deliberate looking — not a casual glance. When Lot's wife nabat toward Sodom, she gazed with attachment. The verb suggests her heart was still there.

Contrast

Compare with Abraham's looking in Genesis 22:13: "And Abraham lifted up his eyes, and looked [vayyar], and behold behind him a ram." Abraham looked forward to God's provision. Lot's wife looked back to destruction.

Cross-Language Connections

| Language | Word | Meaning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek (LXX) | ἐπιβλέπω (epiblepō) | to look upon, gaze at | LXX Gen 19:26 (περιέβλεψεν) |

| Latin (Vulgate) | respicio | to look back | Vulgate Gen 19:26 ("respiciens") |

| English | respect (1828), spectacle (1828), inspect (1828) | All from Latin specere "to look"; respect = re-spicere "to look back at" | — |

Week 09 Study Guide | CFM Corner | OT 2026

File Status: Complete

Created: 2026-02-18

The Challenge

The Akedah can be deeply unsettling to modern readers: Why would God ask a father to sacrifice his son? Teaching it requires sensitivity while honoring its doctrinal depth.

Approach: Type and Shadow

Frame the Akedah as God's way of helping Abraham (and us) understand what the Father would do for us. Every detail is an enacted parable:

| Abraham & Isaac | God the Father & Christ |

|---|---|

| "Take now thy son, thine only son, whom thou lovest" | "God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son" |

| Three-day journey (symbolically, Isaac was "dead" to Abraham for 3 days) | Christ in the tomb for 3 days |

| Isaac carries the wood | Christ carries the cross |

| "God will provide himself a lamb" | Christ is the Lamb of God |

| Mount Moriah | Golgotha / Temple Mount |

| The ram substitutes for Isaac | Christ substitutes for us |

| Abraham receives Isaac back | The Resurrection |

Key quote: Jacob 4:5 — "Abraham... offering up his son Isaac, which is a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son."

Discussion Questions

- How does understanding the Akedah as a type of Christ change how you read it?

- What has God asked you to place on the altar? How did it feel?

- Abraham "rose up early in the morning" (22:3) — he didn't delay his obedience. What does immediate obedience look like in our lives?

Personal Inventory

Invite learners to consider their own "impossible" promises:

- Patriarchal blessings that seem unfulfillable

- Temple covenants regarding eternal families when family members have left the faith

- Healing that hasn't come

- Righteous desires that remain unmet

Sarah's Arc

Sarah's experience models a pattern many can relate to:

- Promise received (Gen. 12–17) — God says it will happen

- Long delay — 25 years of waiting

- Laughter of disbelief (Gen. 18:12) — "It's been too long; I'm too old"

- Fulfillment (Gen. 21:1–2) — "At the set time of which God had spoken"

- Laughter of joy (Gen. 21:6) — "God hath made me to laugh"

Teaching moment: The same emotion (laughter) is transformed from doubt to joy. God doesn't punish the doubt — He fulfills the promise anyway.

What "Looking Back" Looks Like Today

Elder Holland's interpretation: Lot's wife didn't just look back — she looked back longingly. Her heart was still in Sodom.

Modern applications:

- Returning to sins we've repented of

- Idealizing a past relationship or lifestyle

- Refusing to move forward after loss or change

- Clinging to "the way things were" in church, family, or culture

- Scrolling through an ex's social media

The Contrast

Present two postures:

- Lot's wife: Looks back → becomes salt (preserved in the past, unable to move)

- Abraham: Looks up (22:13) → sees God's provision (the ram)

Question: Where are your eyes? Back toward what you've been asked to leave? Or forward toward what God is providing?

The Model

Abraham's intercession for Sodom (Gen. 18:23–33) teaches:

- Boldness in prayer — Abraham pressed God, respectfully but persistently

- The righteous influence the outcome — God would have spared the city for 10 righteous

- Compassion for the wicked — Abraham interceded for a city he knew was sinful

- God invites negotiation — He didn't rebuke Abraham; He answered every appeal

Application

- Who are you interceding for? Family members? Friends who have left the faith?

- Do you pray boldly or timidly?

- President Russell M. Nelson: "The Lord loves effort" — pressing in prayer is not presumptuous; it's faithful

The 25-Year Wait

| Abraham's Age | Event |

|---|---|

| 75 | Promise given (Gen. 12:2–4) |

| 86 | Ishmael born — Abraham's "solution" (Gen. 16:16) |

| 99 | Covenant renewed; circumcision (Gen. 17) |

| 100 | Isaac born — God's timing (Gen. 21:5) |

Abraham waited 25 years from promise to fulfillment. During that time:

- He tried to solve it himself (Ishmael)

- He questioned God (Gen. 15:2 — "what wilt thou give me, seeing I go childless?")

- He laughed (Gen. 17:17)

- Yet he kept walking in covenant

Teaching Moment

God's delay was not denial. The timing ensured:

- Both Abraham and Sarah were biologically incapable → miracle undeniable

- Their faith was tested and refined

- The child was clearly God's doing, not human planning

For those waiting on promises: "At the set time" (lamo'ed) — God operates on appointed times. Our job is to remain in covenant while we wait.

For Families with Children

- Hospitality activity: Plan a service of "Abrahamic hospitality" — make a meal for someone unexpected

- Trust walk: Blindfold a child and guide them (like Abraham going "not knowing" to Moriah) — discuss trusting God

- Name meaning: Discuss how Isaac's name means "laughter" — what name would describe God's promise to your family?

For Youth

- Lot's wife challenge: Identify one thing from your past you keep "looking back" to. Write it down and symbolically let it go

- Altar exercise: What is your "Isaac"? What is the thing you love most that you'd find hardest to give to God?

Week 09 Study Guide | CFM Corner | OT 2026

File Status: Complete

Created: 2026-02-18

Observation Questions

- How many visitors came to Abraham at Mamre? What clues suggest at least one was the LORD?

- What specific acts of hospitality did Abraham perform (18:1–8)?

- What was Sarah's reaction to the promise of a son? Why?

- What is the central question of Genesis 18:14?

- How did Abraham begin his intercession for Sodom (18:23)?

- What numbers did Abraham propose in his negotiation with God?

- At what number did Abraham stop asking? Did God ever say "no"?

Interpretation Questions

- Why does the text shift between "they" and "he/the LORD" when describing the visitors?

- What does Sarah's laughter reveal about her spiritual state at that moment?

- Why did God ask "Wherefore did Sarah laugh?" if He already knew the answer?

- What does Abraham's intercession teach about the nature of prayer?

- Why might Abraham have stopped at ten righteous? Was he afraid to ask further?

- What does "Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?" (18:25) reveal about Abraham's understanding of God?

Application Questions

- What "impossible" promise from God are you waiting on?

- How does Genesis 18:14 speak to your current circumstances?

- Who in your life needs you to intercede for them before God?

- Do you pray boldly like Abraham, or do you hold back? Why?

- What does Abraham's hospitality model for how we receive strangers?

Observation Questions

- Where was Lot when the angels arrived? What does "sitting in the gate" suggest about his position?

- How did the men of Sodom respond to Lot's guests?

- What did the angels do to protect themselves and Lot?

- Who did the angels tell Lot to gather before fleeing?

- What happened to Lot's sons-in-law when he warned them?

- What specific instruction did the angels give about looking back?

- What happened to Lot's wife?

- Where did Lot and his daughters end up?

Interpretation Questions

- How does Sodom's treatment of visitors contrast with Abraham's hospitality in chapter 18?

- What was the core sin of Sodom? (Consider Ezekiel 16:49–50 alongside Genesis 19)

- Why did Lot hesitate to leave (19:16)? What does this suggest?

- What does "looked back" mean beyond a physical glance?

- Why salt specifically? What symbolic connections exist?

- What warning does Lot's wife provide for covenant people today?

Application Questions

- What "Sodoms" has God asked you to leave?

- Are there things you keep "looking back" to longingly?

- Jesus said "Remember Lot's wife" (Luke 17:32). What was He warning about?

- How do you keep moving forward when leaving something familiar and comfortable?

Observation Questions

- How old were Abraham and Sarah when Isaac was born?

- What does the name Isaac mean, and why was it given?

- What did Sarah say about laughter in 21:6?

- What conflict arose between Sarah and Hagar/Ishmael?

- What did Sarah demand Abraham do?

- How did Abraham feel about Sarah's demand?

- What did God tell Abraham to do, and why?

- What happened to Hagar and Ishmael in the wilderness?

- What promise did God make about Ishmael?

Interpretation Questions

- How is Sarah's laughter in 21:6 different from her laughter in 18:12?

- Why did God side with Sarah's demand to send Hagar away?

- What does God's care for Hagar and Ishmael reveal about His character?

- How does "God heard the voice of the lad" (21:17) connect to Ishmael's name ("God hears")?

- What does the 25-year delay between promise and fulfillment teach about faith?

Application Questions

- Have you experienced laughter transforming from doubt to joy?

- When has God's timing seemed impossibly slow but proved perfect?

- How do you respond when God fulfills a long-awaited promise?

- What does God's care for Hagar (who was outside the covenant line) teach about His love?

Observation Questions

- What did God ask Abraham to do in 22:1–2?

- How quickly did Abraham respond (22:3)?

- How long was the journey to Moriah?

- What did Abraham tell his servants in 22:5?

- What did Isaac carry? What did Abraham carry?

- What question did Isaac ask his father?

- What was Abraham's answer?

- What happened when Abraham raised the knife?

- What was provided as a substitute?

- What did Abraham name the place, and what does the name mean?

- What did God promise Abraham after the test (22:15–18)?

Interpretation Questions

- Why does God call Isaac Abraham's "only son" when Ishmael also exists?

- What is the significance of Abraham rising "early in the morning"?

- Why a three-day journey? What typological significance might this have?

- Abraham told the servants "I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you" (22:5). Did Abraham believe Isaac would return alive?

- What are the possible meanings of "God will provide himself a lamb" (22:8)?

- How is Mount Moriah connected to the Temple Mount and Golgotha?

- In what ways is the Akedah a type of Christ's sacrifice? List specific parallels.

- What does "now I know that thou fearest God" (22:12) mean? Didn't God already know?

- How does Hebrews 11:17–19 interpret Abraham's faith during the Akedah?

- What is the significance of the ram being caught "in a thicket"?

Application Questions

- What has God asked you to place on the altar?

- How do you respond when God's commands seem to contradict His promises?

- What does the Akedah teach about the difference between obedience and understanding?

- "God will provide" — how have you seen this principle in your life?

- How does the Akedah deepen your understanding of Heavenly Father's sacrifice of His Son?

Observation Questions

- How old was Sarah when she died?

- Where did Sarah die?

- What did Abraham do in response to Sarah's death (23:2)?

- What did Abraham ask the Hittites for?

- What was Ephron's initial offer? What was the final price?

- What was included in the purchase besides the cave?

Interpretation Questions

- Why does the text record the legal transaction in such detail?

- What is the significance of Abraham's first land purchase being a burial site?

- How does this purchase relate to God's promise of the land of Canaan?

- Why might Abraham have insisted on paying full price rather than accepting a gift?

- Who would eventually be buried at Machpelah?

Application Questions

- What does Abraham's grief for Sarah teach about mourning within faith?

- How does owning a burial plot in the Promised Land express faith in future fulfillment?

- What "first steps" of faith have you taken toward a larger promise?

Faith & Trust

- How does Abraham's faith develop across Genesis 18–23?

- Compare Abraham's response to the promise of Isaac (laughter + worship) with Sarah's (laughter + denial). What's different?

- What is the relationship between faith and waiting in these chapters?

Types of Christ

- List every detail in Genesis 22 that points to Christ.

- How does Abraham's willingness to sacrifice Isaac help us understand John 3:16?