| Church Manuals | |

| Come Follow Me Manual | View |

| Scripture Helps: OT | View |

| OT Seminary Manual | View |

| OT Institute (Gen-2Sam) | View |

| Bible Dictionary | View |

| Topical Guide | View |

| Guide to the Scriptures | View |

| Pearl of Great Price Manual | View |

| Scripture Reference | |

| Bible Dictionary | View |

| Topical Guide | View |

| Guide to the Scriptures | View |

| Church Media | |

| Gospel for Kids | View |

| Bible Videos | View |

| Church Publications & Library | |

| Church Magazines | View |

| Gospel Library | View |

The Call of Abraham and the Abrahamic Covenant

5-Minute Overview

This week we cross one of the great dividing lines of the Bible. For seven weeks we've been in primeval history — Creation, Fall, Flood, Babel. Now, with the call of Abram in Genesis 12, we enter patriarchal history — the intimate, personal story of one family chosen to bless every other family on earth. You'll explore the five promises of the Abrahamic Covenant, meet Melchizedek the mysterious king-priest, encounter Hagar (the first person in the Bible to give God a name), and discover how Hebrew three-letter roots weave a web of covenant vocabulary connecting blessing, righteousness, peace, and holiness.

Weekly Resources: Week 08

Genesis 12–17; Abraham 1–2

Feb 16–22

“I Will Make of Thee a Great Nation”

Official Church Resources

Video Commentary

Specialized Audiences

Reference & Study Materials

"Finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers."

With these words in Abraham 1:2, we hear the voice of a young man whose circumstances could not have been more hostile to his desires. Abraham's father had turned to idol worship. The priests of his community had tried to sacrifice him on an altar. Everything in his world pushed him toward conformity with the religious darkness around him.

And yet Abraham desired.

He desired greater happiness. Greater knowledge. Greater righteousness. These weren't idle wishes—they were holy ambitions that would reshape the entire course of human history. God heard those desires, delivered Abraham from the altar, and called him out of everything familiar into a covenant relationship that would become the foundation for every covenant that followed.

This week we cross one of the great dividing lines of the Bible. For seven weeks, we've been in "primeval history"—Creation, Fall, Flood, Babel. These are stories about all of humanity. Now, with the call of Abram in Genesis 12, we enter "patriarchal history"—the intimate, personal story of one family chosen to bless every other family on earth. The camera narrows from the cosmic to the particular, from all nations to one man standing under the stars, believing an impossible promise.

And the story speaks to us. We all know what it's like to have desires that exceed our circumstances. To want something holy while surrounded by something less. Abraham's story whispers across the millennia: your desires matter. God hears them. Act on them in faith, and watch what He can do.This week's materials are some of the richest we've prepared. You'll find a detailed study of the Abrahamic covenant—the five promises that form the pattern for our own covenant path. You'll meet Melchizedek, the mysterious king-priest who was both a type of Christ and the namesake of the higher priesthood. You'll encounter Hagar, a servant woman in the wilderness who became the first person in the Bible to give God a name. And you'll explore how Hebrew words built from three-letter roots weave a web of covenant vocabulary that connects blessing, righteousness, peace, and holiness into a single, unified theological vision.

Let's begin.

A full study guide is prepared with six files, interactive charts, and this Weekly Insights document. Here's how to find what works best for you:

| Short on time? | Start with the Week Overview — it gives you a complete reading summary, central themes, key figures, and a suggested reading approach for every time level. Pair it with the CFM Manual lesson for a focused, manageable study session. |

|---|---|

| Love deep study? | Historical & Cultural Context — The ancient world Abraham lived in: Mesopotamian covenant rituals (why animals were divided in Genesis 15), Nuzi adoption customs (why Eliezer was Abraham's heir), surrogate motherhood practices (why Sarah gave Hagar), circumcision across cultures, moon worship in Ur, Canaanite and Egyptian religion, archaeological discoveries, Book of Abraham antiquity evidence, and Jewish interpretive traditions. Key Passages Study — 5 passages in extraordinary detail: Abraham's call, his righteous desires, the Abrahamic covenant, Melchizedek and the priesthood, and Abraham counted righteous. Each includes Hebrew word analysis, literary structure, ancient context, cross-references, and Latter-day Saint connections. Word Studies — Five key Hebrew terms with full linguistic analysis: בְּרִית (berith, covenant), זֶרַע (zera', seed), צְדָקָה (tsedaqah, righteousness), Melchizedek, and כֹּהֵן (kohen, priest). |

| Visual learner? | The Genesis–Abraham Comparison Chart shows side-by-side exactly what the Restoration adds to the biblical account — what Abraham 1–2 reveals that Genesis alone does not. The Hebrew Root System Chart maps how this week's covenant vocabulary connects through shared three-letter roots. |

| Following our Hebrew journey? | This week we take a significant step: the Hebrew root system. We've learned the alphabet, the vowels, and the dagesh. Now we discover how Hebrew words are built from three-consonant roots — and how the roots for "bless," "cut a covenant," "righteous," "believe," "peace," and "holy" form an interconnected family of covenant language. More details below. |

| Learn best by watching? | The Weekly Resources page has 15+ video commentaries with summaries to help you choose which to watch. From short overviews to scholarly deep dives, there's something for every schedule. |

| Teaching this week? | The Teaching Applications file has ready-to-use ideas for 7 contexts — personal study, Family Home Evening, Sunday School, Seminary/Institute, Relief Society/Elders Quorum, Primary, and Missionary Teaching. Each includes specific activities, discussion questions, and scripture selections. |

| Want study questions? | The Study Questions file has questions organized by category for individual reflection, group discussion, or journal prompts. |

Over the past three weeks, we've built a foundation in Hebrew: the 22 consonants of the alphabet (Week 5), the vowel system (Week 6), and the dagesh with its letter classifications (Week 7). This week we take what may be the most illuminating step yet — understanding how Hebrew words are actually built.

Unlike English, where words are built from prefixes, suffixes, and independent roots that don't always relate to each other, Hebrew words are constructed from three-consonant roots called a שֹׁרֶשׁ (shoresh, literally "root"). These three letters carry a core meaning, and by adding vowels and prefixes/suffixes, Hebrew generates entire families of related words from a single root.

Think of it like a tree: the three-letter root is the trunk, and every word formed from that root is a branch — different in form but connected in meaning.

This matters for Bible study because recognizing roots reveals connections invisible in English translation. Words that seem unrelated in English often share the same Hebrew root, linking concepts that the original authors intended to connect.

Abraham's story introduces a cluster of Hebrew roots that form the vocabulary of covenant. Here are six root families you'll encounter this week:

| Word | Hebrew | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| barak | בָּרַךְ | to bless, to kneel |

| berakhah | בְּרָכָה | blessing |

| barukh | בָּרוּךְ | blessed |

The root B-R-K appears five times in the covenant call of Genesis 12:2–3 alone. The original meaning connects to kneeling — one kneels to receive a blessing, and one kneels to give thanks for being blessed. Melchizedek blessed Abraham (Genesis 14:19), and through Abraham all families of the earth would be blessed. The covenant is, at its heart, a cascade of blessing flowing from God through Abraham to the world.

| Word | Hebrew | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| karat | כָּרַת | to cut, to cut off |

| karat berith | כָּרַת בְּרִית | to cut a covenant (i.e., to make a covenant) |

The Hebrew idiom for making a covenant is karat berith — literally "to cut a covenant." This comes from the ancient ceremony in Genesis 15:9–18, where animals were divided and the covenant-maker passed between the pieces. The ritual symbolized: "May I become like these animals if I break this covenant." In Genesis 15, God Himself — as a smoking furnace and burning lamp — passed between the pieces, binding Himself to the covenant. Abraham didn't walk through. God bore the full weight of the covenant obligation.

| Word | Hebrew | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| tsedeq | צֶדֶק | righteousness, justice |

| tsedaqah | צְדָקָה | righteousness (relational) |

| tsaddiq | צַדִּיק | righteous person |

| Malki-Tsedeq | מַלְכִּי־צֶדֶק | "My King is Righteousness" (Melchizedek) |

When Genesis 15:6 says Abraham's faith was "counted to him for righteousness," the word is צְדָקָה (tsedaqah). This same root gives us Melchizedek's name — Malki-Tsedeq, "King of Righteousness." Abraham's faith and Melchizedek's identity are woven from the same linguistic thread.

| Word | Hebrew | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| he'emin | הֶאֱמִין | he believed, trusted |

| emunah | אֱמוּנָה | faithfulness, steadfastness |

| amen | אָמֵן | truly, so be it |

| emet | אֱמֶת | truth |

"And he believed (הֶאֱמִין) in the LORD" (Genesis 15:6). The root Aleph-M-N carries the idea of firmness, reliability, trust. When we say "Amen" at the end of a prayer, we're using this same root — affirming that what has been said is firm and true. Abraham's faith wasn't a fleeting feeling; it was a settled, firm trust in God's character and promises, even when the evidence pointed the other way.

| Word | Hebrew | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| shalom | שָׁלוֹם | peace, wholeness, well-being |

| Shalem | שָׁלֵם | Salem (Melchizedek's city) |

| shalem | שָׁלֵם | complete, whole, at peace |

Melchizedek was king of Salem (שָׁלֵם) — a name built from the root for peace and wholeness. Hebrews 7:2 translates it directly: "King of Salem, which is, King of peace." Jerusalem (Yerushalayim) also derives from this root — the "city of peace." So Melchizedek was the King of Righteousness (tsedeq) reigning in the city of Peace (shalom). Two Hebrew roots, woven together in one figure who points forward to Christ, the true Prince of Peace (Isaiah 9:6).

| Word | Hebrew | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| qadosh | קָדוֹשׁ | holy, set apart |

| qiddesh | קִדֵּשׁ | to sanctify, make holy |

| miqdash | מִקְדָּשׁ | sanctuary, holy place |

The root Q-D-Sh means "to set apart." Abraham was set apart from his idolatrous family, set apart by covenant, set apart for a sacred mission. The altars he built at Shechem, Bethel, and Hebron were acts of qiddush — sanctifying the land, establishing holy ground in the midst of Canaanite idolatry. This same root will later give us miqdash (sanctuary/temple) and qadosh (the holy one) — words that define the sacred spaces and sacred identity that flow from the Abrahamic covenant.

What's remarkable is how these roots interweave. The one who is blessed (B-R-K) cuts a covenant (K-R-T) and is counted righteous (Ts-D-Q) because he believes (Aleph-M-N), finding peace (Sh-L-M) in the holy (Q-D-Sh) relationship God establishes with him. Hebrew doesn't just describe the covenant — its very vocabulary is the covenant, with each root reinforcing the others.

For a visual map of these root connections, see the Hebrew Root System Chart. And if you're building on previous weeks, the Hebrew Alphabet Chart, Vowels Chart, and Dagesh & Letter Guide remain available for reference.

If you had to point to one passage of scripture that shapes everything that follows — every covenant, every priesthood ordinance, every temple blessing, every missionary effort — it might well be Abraham 2:9–11. Here God lays out the covenant in its fullest form, clarifying what Genesis states briefly and what the Restoration reveals completely.

The Abrahamic covenant contains five interconnected promises:

| Promise | Scripture | Modern Fulfillment |

|---|---|---|

| Land | "All the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession" (Genesis 17:8) | Celestial inheritance; eternal dwelling with God |

| Posterity | "I will make thy seed as the dust of the earth" (Genesis 13:16) | Eternal increase through temple sealing |

| Priesthood | "In their hands they shall bear this ministry and Priesthood unto all nations" (Abraham 2:9) | Melchizedek Priesthood authority and temple ordinances |

| Gospel Blessings | "The blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal" (Abraham 2:11) | The fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ |

| Ministry | "In thee shall all families of the earth be blessed" (Genesis 12:3) | Missionary work and temple work for the dead |

Notice the outward-facing dimension: this covenant is not just for Abraham. It flows through Abraham to bless everyone else. "As many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed" (Abraham 2:10). The covenant creates a people whose purpose is to bless other peoples.

One of the most striking scenes in all of scripture occurs in Genesis 15:9–18. God instructed Abraham to take a heifer, a goat, a ram, a turtledove, and a pigeon, divide them, and arrange the halves opposite each other. Then, as darkness fell, "a smoking furnace, and a burning lamp... passed between those pieces" (Genesis 15:17).

This was the ancient ceremony of karat berith — "cutting a covenant." In the ancient Near East, both parties would walk between the divided animals, symbolically declaring: "May I become like these animals if I break this covenant."

But notice what happened in Genesis 15: only God passed between the pieces. Abraham watched. The smoking furnace and burning lamp — symbols of God's presence — moved through alone. God bore the full weight of the covenant obligation. This was not a mutual contract between equals. This was a divine promise, unilateral and unconditional, in which God bound Himself to Abraham's future.

The Hebrew idiom captures the gravity: כָּרַת בְּרִית (karat berith) — to cut a covenant. Covenants in the ancient world were not signed. They were cut. They cost something. They involved blood.

At first glance, this ceremony can feel alien — a strange ritual from a world nothing like ours. But look closer at what passed between those pieces: a smoking furnace and a burning lamp. Fire and light. Throughout scripture, this is how God shows up. He was the fire in the burning bush that spoke to Moses — a flame that burned but did not consume (Exodus 3:2). He was the pillar of fire that led Israel through the darkness of the wilderness (Exodus 13:21). He was the light of the menorah in the tabernacle — a lamp that was never to go out (Leviticus 24:2–4), and which Jewish tradition connects to the Tree of Life itself. And centuries later, Christ would stand in the temple at the Feast of Tabernacles — while the great lampstands blazed in the Court of Women — and declare: "I am the light of the world" (John 8:12).

The ceremony in Genesis 15 is not a relic of a primitive past. It is the same message God has been sending from the beginning: I will be the light in the middle of the covenant. When Abraham asked how he could know that God's promises were sure, God did not hand him a signed contract. He walked through the cost Himself, as fire and light, and said: I am the guarantee.This is what makes the Abrahamic covenant different from every other ancient treaty. In a typical covenant, both parties bore the consequences of failure. But God passed through alone. He took the full obligation upon Himself. And when the covenant was eventually broken — not by God, but by His people — He kept His word. The cost fell on Him. The Lamb of God, foreshadowed by those divided animals, bore in His own body what the covenant demanded (Isaiah 53:5; 1 Peter 2:24).

At the heart of every covenant — ancient or modern — is not a ritual, not an obligation, not even a promise. It is a Person. The burning lamp that passed between the pieces is the same light that meets us at the waters of baptism, in the temple, and at the sacrament table. The form changes. The Presence does not.

Paul declared: "If ye be Christ's, then are ye Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise" (Galatians 3:29). Abraham 2:10 confirms: "As many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed."

We enter the Abrahamic covenant through baptism and receive its fulness through temple ordinances. President Russell M. Nelson has taught: "The covenant path is all about our relationship with God" (Liahona, May 2023). Each step along the covenant path echoes elements of the Abrahamic covenant:

- Baptism — Entry into the covenant; becoming Abraham's seed

- Gift of the Holy Ghost — The seal of the covenant promise

- Temple Endowment — Receiving covenant knowledge and priesthood blessings

- Temple Sealing — Eternal marriage, eternal seed, eternal increase

The promises made to Abraham are not ancient history. They are present-tense invitations extended to every person who receives the gospel.

If all you read was Genesis 12, you might think Abraham's story began with a simple divine command: "Get thee out of thy country" (Genesis 12:1). But Abraham 1 reveals a far more dramatic backstory.

Abraham's father Terah had "turned from his righteousness, and from the holy commandments which the Lord his God had given unto him, unto the worshiping of the gods of the heathen" (Abraham 1:5). This was not passive spiritual drift. Terah actively participated in a system that practiced human sacrifice. Abraham himself was placed upon an altar by the priest of Pharaoh, and only divine intervention — the Lord destroying the altar and its priest — saved his life (Abraham 1:7–15).

Think about what that means. Abraham's desire to follow God wasn't formed in a supportive home. It was forged in active persecution, in a family that had abandoned truth, in a culture that would literally kill him for his beliefs.

"Finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers, and the right whereunto I should be ordained to administer the same; having been myself a follower of righteousness, desiring also to be one who possessed great knowledge, and to be a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge, and to be a father of many nations, a prince of peace, and desiring to receive instructions, and to keep the commandments of God, I became a rightful heir, a High Priest."

Notice the pattern of escalation. Abraham was already "a follower of righteousness" — but he desired to be a greater follower. He already possessed knowledge — but he wanted greater knowledge. He didn't rest in his current spiritual state. He reached upward.

This is the pattern of "grace for grace" (D&C 93:12), "line upon line, precept upon precept" (2 Nephi 28:30). Abraham models what it looks like to not be satisfied with where you are spiritually — not out of anxiety or guilt, but out of holy desire for more of God.

Sarah (originally Sarai) is sometimes overlooked in the Abrahamic narrative, but she is a full covenant partner. God changed her name too — from Sarai to Sarah (שָׂרָה, "princess") — and explicitly included her in the covenant promise: "I will bless her, and give thee a son also of her" (Genesis 17:16).

Sarah followed Abraham out of Ur, through Haran, into Canaan, down to Egypt, and back — leaving everything she knew on the strength of promises she would not see fulfilled for decades. Hebrews 11:11 honors her specifically: "Through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive seed, and was delivered of a child when she was past age, because she judged him faithful who had promised."

Sarah's faith was not passive. She judged God faithful. She made an active assessment of God's character and chose to believe His promise even when biology said it was impossible. That is covenant faith.

In the midst of patriarchs and covenants and priesthood, Genesis 16 turns the camera to an unexpected figure: Hagar, Sarah's Egyptian servant.

When Sarah remained childless after years of waiting, she gave Hagar to Abraham as a wife — a culturally acceptable practice in the ancient Near East but one that introduced deep conflict into the household. When Hagar conceived and tension erupted, Hagar fled into the wilderness.

There, alone and desperate, the Angel of the LORD found her by a spring of water (Genesis 16:7). This is the first angelic visitation recorded in the Bible — and it went not to a patriarch, not to a prophet, but to a pregnant servant woman fleeing her mistress.

The angel told Hagar to return, promised that her son would become a great nation, and instructed her to name him Ishmael — יִשְׁמָעֵאל (Yishma'el), meaning "God hears."Hagar's response is extraordinary. She "called the name of the LORD that spake unto her, Thou God seest me" — אֵל רֳאִי (El Roi, "God Who Sees") (Genesis 16:13). Hagar is the first person in the Bible to give God a name. Not Abraham. Not Moses. Hagar.

The theological implications are profound:

- God sees the marginalized. Hagar had no social standing, no covenant status, no claim on divine attention. Yet God found her, spoke to her, and made promises about her future.

- God hears. The name Ishmael — "God hears" — declares that God listens to the cries of those in distress, regardless of their position in the social or covenant hierarchy.

- The first angelic visitation goes to a servant. Before an angel appeared to Moses at the burning bush, before an angel spoke to Gideon or Manoah or Mary — an angel appeared to Hagar. God's order of priority is not the world's.

- Naming God. Hagar didn't just receive revelation — she contributed to it. Her name for God, El Roi, entered the theological vocabulary of Israel. A servant woman expanded humanity's understanding of God's character.

In a week focused on covenant and priesthood and patriarchs, Hagar's story reminds us that God's concern extends beyond covenant boundaries. He sees. He hears. He comes to the spring in the wilderness.

Melchizedek appears without introduction in Genesis 14:18 — "And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God." Three verses. No genealogy, no origin story, no explanation of how a righteous king-priest came to be ruling in Canaan.

His name tells us everything we need to know: מַלְכִּי־צֶדֶק (Malki-Tsedeq) — "My King is Righteousness" or, as Hebrews 7:2 translates it, "King of righteousness." He was king of שָׁלֵם (Shalem) — "King of peace." Both king and priest. Righteousness and peace united in one person.

While Genesis gives us three verses, the Joseph Smith Translation of Genesis 14 expands the account dramatically. JST Genesis 14:25–40 reveals that Melchizedek:

- Was "a man of faith, who wrought righteousness; and when a child he feared God, and stopped the mouths of lions, and quenched the violence of fire" (v. 26)

- Was "ordained an high priest after the order of the covenant which God made with Enoch" (v. 27)

- Held a priesthood that came "not by man, nor the will of man; neither by father nor mother; neither by beginning of days nor end of years; but of God" (v. 28)

- "Obtained peace in Salem, and was called the Prince of peace" (v. 33)

- Led a people who "wrought righteousness, and obtained heaven, and sought for the city of Enoch" (v. 34)

Melchizedek didn't just hold priesthood — he used it to transform an entire city. Salem became a place of peace through righteousness. His people sought after the translated city of Enoch, establishing a Zion community centuries before Moses.

The parallels between Melchizedek and Christ are deliberate and detailed:

| Melchizedek | Christ |

|---|---|

| King of Righteousness (meaning of name) | "The LORD Our Righteousness" (Jeremiah 23:6) |

| King of Peace (Salem = shalom) | Prince of Peace (Isaiah 9:6) |

| Priest of the Most High God | Great High Priest (Hebrews 4:14) |

| No recorded genealogy (Hebrews 7:3) | Eternal Son of God |

| Brought forth bread and wine | Instituted the sacrament |

| Blessed Abraham | Blesses all who come to Him |

| Received tithes | Receives our offerings |

| Both king and priest | Both king and priest (Zechariah 6:13) |

When Abraham returned from rescuing Lot, Melchizedek blessed him, and Abraham "gave him tithes of all" (Genesis 14:20). This is the first mention of tithing in scripture — predating the Mosaic law by centuries.

The Hebrew מַעֲשֵׂר (ma'aser) means "a tenth part." Abraham's payment acknowledged both Melchizedek's priesthood authority and the principle that all increase comes from God. Immediately after, the king of Sodom offered Abraham all the spoils of war. Abraham refused: "I will not take from a thread even to a shoelatchet... lest thou shouldest say, I have made Abram rich" (Genesis 14:23). Abraham's prosperity came from God, not from worldly sources.

The priesthood's true name is "the Holy Priesthood, after the Order of the Son of God." Melchizedek's name became the title out of reverence for God's name. D&C 84:14 confirms that Abraham himself "received the priesthood from Melchizedek."

Alma 13:14–19 in the Book of Mormon provides additional testimony: Melchizedek's people "did establish peace in the land in his days; therefore he was called the prince of peace... and his people wrought righteousness, and obtained heaven." Alma uses Melchizedek as the prime example of how the Melchizedek Priesthood is meant to function — not merely in ordinances but in transforming communities.In the ancient world, a name was not merely a label — it was a declaration of identity and destiny. When God changed Abram's name to Abraham, and Sarai's name to Sarah, He was doing something far more significant than updating their records.

Abram (אַבְרָם, 'Avram) means "exalted father." Abraham (אַבְרָהָם, 'Avraham) means "father of a multitude." The added letter ה (heh) is drawn from God's own name — יהוה (YHWH). God literally inserted part of His own name into Abraham's identity. The same happened with Sarai → Sarah — both received the heh from God's name. Genesis 17:5 explains the wordplay: "For a father of many nations ('av hamon goyim) have I made thee." God declared Abraham's identity before the physical fulfillment — Sarah was still barren when the name changed. This is what Paul calls "calling those things which be not as though they were" (Romans 4:17). God names our future before we arrive there.Along with the name change, God instituted circumcision as the outward sign ('ot, אוֹת) of the covenant (Genesis 17:11). The Hebrew word translated "token" is the same word used for the rainbow sign of the Noahic covenant (Genesis 9:12). Every covenant comes with a sign — a physical reminder of spiritual reality.

Circumcision marked the body with covenant identity. It was permanent, personal, and carried out on the organ of generation — connecting the covenant sign to the promise of seed. Every circumcised male in Israel carried the Abrahamic covenant literally in his flesh.

We don't practice circumcision as a covenant sign today — the "new covenant" brought a "circumcision of the heart" (Jeremiah 4:4; Romans 2:29). But the principle of covenant names and covenant identity continues:

- Baptism: We take upon ourselves the name of Christ (Mosiah 5:8–12; D&C 20:37). Like Abraham receiving a new name, we receive a new identity.

- Temple Ordinances: New names and covenant identities are conferred in the temple, echoing the pattern established with Abraham and Sarah.

- The Sacrament: Each week we renew our willingness to "take upon [us] the name of [the] Son" (Moroni 4:3) — recommitting to our covenant identity.

Abraham's name change teaches a powerful principle: God names us for what we are becoming, not just for what we have been. Abraham was called "father of a multitude" when he had no children by Sarah. God sees our covenant future and declares it over us in the present.

The Week 8 Study Guide contains six comprehensive files to support your study:

- The Call of Abraham (Genesis 12:1–3; Abraham 2:3–6)

- Abraham's Righteous Desires (Abraham 1:1–4)

- The Abrahamic Covenant (Abraham 2:9–11; Genesis 17:1–8)

- Melchizedek and the Priesthood (Genesis 14:18–20; JST Genesis 14:25–40)

- Abraham Counted Righteous (Genesis 15:1–6)

Each includes literary structure, Hebrew word analysis, cross-references, and Latter-day Saint connections.

- בְּרִית (berith) — "covenant"

- זֶרַע (zera') — "seed/offspring"

- צְדָקָה (tsedaqah) — "righteousness"

- מַלְכִּי־צֶדֶק (Malki-Tsedeq) — "Melchizedek"

- כֹּהֵן (kohen) — "priest"

As you study this week, consider:

- On Holy Desires: Abraham desired "to be a greater follower of righteousness" even though he was already righteous (Abraham 1:2). What would it look like for you to pursue greater righteousness from where you currently stand? What holy desires are stirring in you right now?

- On Circumstances: Abraham's family was idolatrous and hostile to his faith. Yet his desires overcame his environment. What circumstances in your life feel like obstacles to your spiritual growth? How does Abraham's example reframe those obstacles?

- On the Covenant Ceremony: In Genesis 15, God alone passed between the divided animals, bearing the full weight of the covenant obligation. What does this teach about who bears the primary responsibility in your covenant relationship with God? How does this change how you think about grace and works?

- On Hagar: The first angelic visitation in the Bible went to a servant woman with no covenant status. What does this reveal about God's priorities? Who are the "Hagars" in your community — people who may feel unseen but whom God knows by name?

- On Covenant Names: God renamed Abraham and Sarah before the promises were fulfilled — declaring their destiny before they could see it. Has God ever spoken identity over you that you couldn't yet see in yourself? How does your covenant identity (as a child of God, as Abraham's seed) shape how you see yourself?

- On Melchizedek: Melchizedek used his priesthood not just for personal righteousness but to transform an entire city into a place of peace. How can priesthood authority and covenant power be used to create "Salem" — places of peace — in your home, ward, or community?

Abraham's story didn't begin with a divine visitation. It began with a desire.

"Finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers" (Abraham 1:2).

Before the covenant, before the priesthood, before the promise of innumerable seed — there was a young man in an idolatrous city who simply wanted more. More righteousness. More knowledge. More of God.

That desire was enough.

God didn't wait for Abraham to become perfect. He didn't require Abraham to first fix his family, escape his culture, or prove himself worthy through years of perfect obedience. God met Abraham in the wanting. He took Abraham's desire and built upon it one of the greatest covenants in all of history.

If you feel a stirring toward greater righteousness, greater knowledge, greater closeness to God — that feeling is not accidental. It is the echo of Abraham's desire resonating through the ages. It is the covenant calling you forward.

You don't need to see the destination. Abraham didn't. God told him to go to "a land that I will shew thee" — future tense, sight unseen. Abraham went anyway. "So Abram departed, as the LORD had spoken unto him" (Genesis 12:4).

The desire is enough to begin. God will show you the land.

Weekly Insights | CFM Corner | OT 2026 Week 08: Genesis 12–17; Abraham 1–2

Week 8

Genesis 12–17; Abraham 1–2

| Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Week | 08 |

| Dates | February 16–22, 2026 |

| Reading | Genesis 12–17; Abraham 1–2 |

| CFM Manual | Genesis 12–17; Abraham 1–2 Lesson |

| Total Chapters | 8 (Genesis 12–17 plus Abraham 1–2) |

| Approximate Verses | ~180 verses |

This week marks a pivotal transition in the biblical narrative—from the primeval history (Creation, Fall, Flood, Babel) to the patriarchal narratives that will dominate the rest of Genesis. We meet Abram (later Abraham), a man whose desire was "to be a greater follower of righteousness" (Abraham 1:2) despite coming from an idolatrous family. God's call to Abraham and the covenant He established with him became the foundation for all subsequent covenants in scripture—and the pattern for our own covenant relationship with God.

Abraham 1 reveals the backstory unknown from Genesis alone. We learn that Abraham's father Terah had "turned from his righteousness" to idol worship (Abraham 1:5), and that Abraham himself narrowly escaped being sacrificed on an altar by the priest of Pharaoh (vv. 7–15). The Lord delivered Abraham, destroyed the altar and its priest, and promised to lead Abraham "by my hand" (v. 18). This chapter also introduces the facsimiles from the Book of Abraham, providing visual representations of Egyptian religious contexts.

Abraham 2 contains the most complete account of the Abrahamic covenant. God promises Abraham: (1) land for his posterity, (2) innumerable seed, (3) the priesthood, and (4) that through his ministry "all the families of the earth [shall] be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal" (v. 11). This is the missionary dimension of the covenant—Abraham's seed become a blessing to others.

Genesis 12 parallels Abraham 2 but in briefer form. God calls Abram to leave Ur/Haran for "a land that I will shew thee" (v. 1). The covenant promises are given: a great nation, a great name, blessing to all families of the earth (vv. 2–3). Abram travels through Canaan, builds altars at Shechem and Bethel, and sojourns briefly in Egypt during a famine.

Genesis 13 recounts Abram's separation from his nephew Lot. When conflict arose between their herdsmen, Abram—the peacemaker—gave Lot first choice of the land. Lot chose the well-watered Jordan valley, settling near Sodom. God then renewed His promise to Abram: "All the land which thou seest, to thee will I give it, and to thy seed for ever" (v. 15).

Genesis 14 introduces Melchizedek, king of Salem and "priest of the most high God" (v. 18). After Abram rescued Lot from invading kings, Melchizedek blessed him and received tithes from him—the first mention of tithing in scripture. The Joseph Smith Translation expands this account significantly, revealing Melchizedek as a great prophet and high priest.

Genesis 15 records a covenant-making ceremony. Abram expressed concern about having no heir, and God showed him the stars: "So shall thy seed be" (v. 5). "And he believed in the LORD; and he counted it to him for righteousness" (v. 6)—a verse quoted extensively in the New Testament. God then passed between divided animals in a "smoking furnace" and "burning lamp," symbolically binding Himself to the covenant (vv. 17–18).

Genesis 16 tells the story of Hagar. When Sarai remained childless, she gave her servant Hagar to Abram as a wife (a culturally acceptable practice). Hagar conceived and conflict arose. Fleeing into the wilderness, Hagar encountered the Angel of the LORD, who told her to return and promised that her son would become a great nation. She named God "El Roi"—"Thou God seest me" (v. 13). Ishmael's name means "God hears."

Genesis 17 establishes circumcision as the sign of the covenant. God changed Abram's name ("exalted father") to Abraham ("father of a multitude") and Sarai to Sarah ("princess"). God promised that Sarah would bear Isaac despite their advanced age. Abraham was 99 years old, and Sarah 90 (Genesis 17:17), when this promise came.

Theme 1: The Abrahamic Covenant—Foundation of All Covenants

The covenant God made with Abraham is not merely an ancient agreement—it is the pattern for the covenant relationship God offers to each of us. The promises God made to Abraham continue in his posterity, "and as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed" (Abraham 2:10).

The covenant includes several interconnected promises:

- Land: A promised inheritance, pointing ultimately to celestial glory

- Posterity: Seed as numerous as the stars, including eternal increase

- Priesthood: The authority to administer the ordinances of salvation

- Gospel Blessings: The fullness of salvation and exaltation

- Ministry: Abraham's seed become a blessing to all families of the earth

President Russell M. Nelson has emphasized that we enter this covenant through baptism and more completely through temple ordinances: "The covenant path is all about our relationship with God" (Liahona, May 2023).

Theme 2: Righteous Desires Amid Unrighteous Circumstances

Abraham's story demonstrates that personal righteousness is possible regardless of family background. His father Terah worshiped idols and conspired to have Abraham killed. Yet Abraham's "desire was to be a greater follower of righteousness" (Abraham 1:2).

Elder Neil L. Andersen taught: "We are all influenced by our families [and] our culture, and yet I believe there is a place inside of us that we uniquely and individually control and create. … Eventually, our inner desires are given life and they are seen in our choices and in our actions."

Abraham desired:

- Greater happiness

- To be a father of many nations

- To possess greater knowledge

- To be a prince of peace

- To receive instructions and keep God's commandments

These holy desires led Abraham to risk everything—and God honored those desires with one of the greatest blessings in all scripture.

Theme 3: Melchizedek—A Type of Christ

The brief mention of Melchizedek in Genesis 14 introduces one of the most enigmatic and significant figures in scripture. The Joseph Smith Translation (JST Genesis 14:25–40) reveals that Melchizedek was:

- Ordained under the hand of God

- A man of faith who "wrought righteousness" from childhood

- The one who established peace in Salem (Jerusalem)

- A high priest "after the order of the covenant which God made with Enoch"

- One who, like Enoch, established a Zion people

Melchizedek is a type of Christ:

- His name means "King of Righteousness"

- He was King of Salem (Peace)

- He was both king and priest

- He had no recorded genealogy (Hebrews 7:3)

- The higher priesthood bears his name

Theme 4: "God Hears"—El Shaddai and Divine Care

This week introduces two important divine names:

El Shaddai (אֵל שַׁדַּי) — "God Almighty" (Genesis 17:1). This name emphasizes God's power to fulfill seemingly impossible promises. The root may relate to mountains or breasts (as a nursing mother), suggesting both strength and nurture.

El Roi (אֵל רֳאִי) — "God Who Sees" (Genesis 16:13). Hagar, alone in the wilderness, discovered that God sees the marginalized and afflicted.

The name Ishmael (יִשְׁמָעֵאל) means "God hears." Even in situations of conflict and displacement, God heard Hagar's cry and blessed her son.

Theme 5: The Tithe—Acknowledging God as the Source

When Melchizedek blessed Abraham, "he gave him tithes of all" (Genesis 14:20). This is the first mention of tithing in scripture, predating the Mosaic law by centuries.

Abraham's response to the king of Sodom is equally instructive. The king offered Abraham all the spoils of war, but Abraham refused: "I will not take from a thread even to a shoelatchet, and that I will not take any thing that is thine, lest thou shouldest say, I have made Abram rich" (Genesis 14:23).

Abraham's prosperity came from God, not from worldly sources. His payment of tithes acknowledged this truth.

| Person | Role | Significance This Week |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham (Abram) | Patriarch, Prophet | Receives the foundational covenant; demonstrates faith despite family idolatry |

| Sarah (Sarai) | Matriarch, Princess | Covenant partner with Abraham; receives name change and promise of Isaac |

| Lot | Abraham's nephew | Separates from Abraham; chooses Sodom; foreshadows next week's tragedy |

| Melchizedek | King of Salem, High Priest | Type of Christ; receives Abraham's tithes; establishes peace in Salem |

| Hagar | Sarah's servant | Becomes Abraham's wife; mother of Ishmael; encounters God in the wilderness |

| Ishmael | Abraham's firstborn | "God hears"; promised to become a great nation; father of 12 princes |

| Terah | Abraham's father | Turned from righteousness to idolatry; conspired against Abraham |

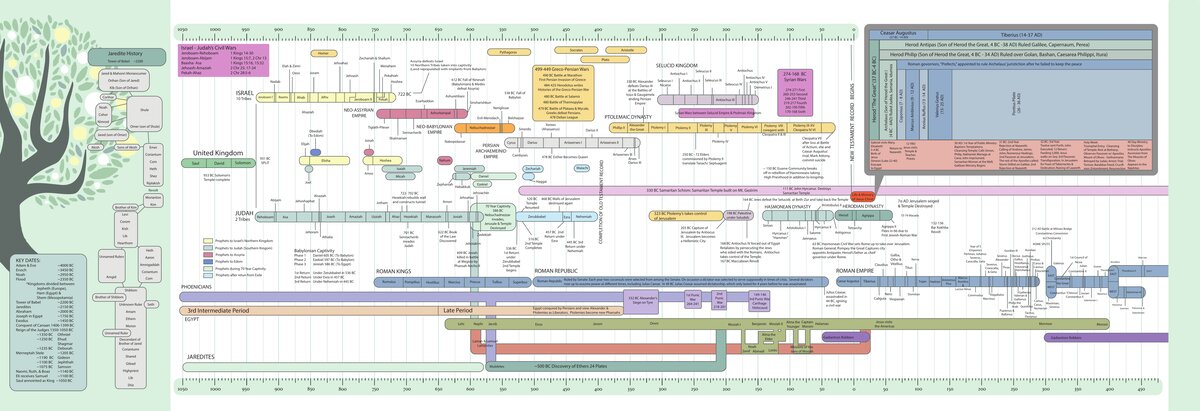

Historical Period: Middle Bronze Age / Patriarchal Period

Approximate Dates: Traditional dating places Abraham circa 2000–1800 BC. Abraham was 75 years old when he left Haran (Genesis 12:4) and 99 when circumcision was instituted (Genesis 17:1).

Biblical Timeline Position: This marks the transition from "primeval history" (Genesis 1–11) to "patriarchal history" (Genesis 12–50). The genealogies of Genesis 11 connect Noah to Abraham.

Relationship to Previous Weeks

Week 07 (Genesis 6–11; Moses 8): The Tower of Babel scattering and the genealogy from Shem to Abram set the stage for Abraham's call. The themes of scattering and gathering continue—Babel scattered humanity; the Abrahamic covenant initiates God's gathering.

Week 08 (Genesis 12–17; Abraham 1–2): Abraham's call and covenant.

Week 09 (Genesis 18–23): Abraham's continued journey, Isaac's birth, the sacrifice of Isaac.

Book of Abraham (Chapters 1–2)

- Author: Abraham, translated by Joseph Smith

- Translation Date: 1835–1842

- Original Audience: Abraham's posterity

- Setting: Ur of the Chaldees, Haran, Canaan

- Purpose: To preserve the record of Abraham's origins, priesthood, and covenant

- Key Themes: Priesthood, covenant, deliverance, astronomy/cosmology

- Literary Genre: Autobiographical narrative

Book of Genesis (Chapters 12–17)

- Author: Traditionally Moses; from earlier patriarchal records

- Source Date: Patriarchal sources possibly dating to Abraham's time

- Original Audience: Ancient Israel

- Setting: Mesopotamia, Canaan, Egypt

- Purpose: To establish covenant origins and Abraham's example of faith

- Key Themes: Covenant, promise, faith, blessing

- Literary Genre: Patriarchal narrative

Book of Mormon Connections

- 2 Nephi 8:2: "Look unto Abraham your father, and unto Sarah that bare you"

- Alma 13:14–19: Melchizedek as a type of Christ and exemplar of faith

- 3 Nephi 20:25–27: The covenant with Abraham fulfilled through the house of Israel

Doctrine and Covenants Connections

- D&C 84:14: Abraham received priesthood from Melchizedek

- D&C 107:1–4: The Melchizedek Priesthood named to avoid too frequent use of the name of Deity

- D&C 110:12: Elias committed "the dispensation of the gospel of Abraham"

- D&C 132:29–32: Abraham received all things by revelation; eternal marriage and exaltation

Pearl of Great Price Connections

- Abraham 1–2: Primary reading this week

- Abraham 3: Abraham's vision of the premortal existence (referenced in covenant)

- The Abrahamic Covenant: God's promise of land, posterity, priesthood, and gospel blessings—the pattern for all subsequent covenants (Genesis 12:1–3; Abraham 2:9–11).

- Melchizedek Priesthood: The higher priesthood, named after a righteous king who was both priest and king, a type of Christ (Genesis 14:18–20; Alma 13:14–19).

- Adoption into the Covenant: All who receive the gospel become Abraham's seed and heirs to the promises (Abraham 2:10; Galatians 3:29).

- Divine Deliverance: God rescues the faithful from danger and persecution, as He did Abraham from the altar (Abraham 1:15–17).

- Covenant Names: Name changes signify covenant status—Abram to Abraham, Sarai to Sarah (Genesis 17:5, 15).

- Tithing: Abraham paid tithes to Melchizedek, establishing the principle before the Mosaic law (Genesis 14:20).

- El Shaddai and Divine Care: God reveals Himself as "God Almighty"—able to fulfill impossible promises, including children to the aged Abraham and Sarah (Genesis 17:1).

The temple themes in this week's reading are abundant:

- Covenant Making: The ceremony in Genesis 15 (passing between divided animals) reflects ancient covenant-making rituals echoed in temple worship

- Altar Building: Abraham builds altars at Shechem, Bethel, and Hebron—establishing sacred spaces for worship

- Melchizedek's Order: The Melchizedek Priesthood, which administers temple ordinances, bears the name of the king-priest who blessed Abraham

- Name Changes: Abram/Abraham and Sarai/Sarah receive new covenant names, as do participants in temple ordinances

- Circumcision: Described as a "token" of the covenant—a physical sign of covenant commitment

- Salem/Jerusalem: Melchizedek's city Salem is identified with Jerusalem, the future location of Solomon's Temple

Manual Focus: Abraham's desire for righteousness despite his family background; the Abrahamic covenant and its application to us; Melchizedek as a man of faith; tithing; God's hearing and seeing of those in need.

Key Questions from Manual:

- What did Abraham desire? How were his desires evident in his actions?

- Why is it important to know about the covenant God made with Abraham?

- What Christlike qualities do you find in Melchizedek?

- What do you learn about Abraham's attitude toward wealth?

- How has God shown you that He has heard you?

Manual's Suggested Activities:

- Lead children by the hand (teaching God's guidance—Abraham 1:18; 2:8)

- Act out the peacemaker story (Genesis 13:5–12)

- Share the stories of Abraham's deliverance and Hagar's encounter with God

If You Have Limited Time (Essential Reading):

- Abraham 1:1–19 — Abraham's background and deliverance

- Abraham 2:6–11 — The fullest version of the covenant

- Genesis 15:1–18 — The covenant ceremony

- Genesis 17:1–14 — Circumcision covenant, name changes

If You Have More Time (Full Reading with Highlights):

- Read all assigned chapters, noting:

- Covenant language and promises

- Altar locations and their significance

- Character traits of Abraham and Sarah

- Parallels between Abraham 1–2 and Genesis 12–17

For Deep Study:

- Compare JST Genesis 14:25–40 with Alma 13 on Melchizedek

- Trace the Abrahamic covenant through D&C 132

- Study the Book of Abraham facsimiles and explanations

The following scholarly essays provide deep background on this week's readings:

| Resource | Title | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| KnoWhy OTL07A | If "All Are Alike Unto God," Why Were Special Promises Reserved for Abraham's Seed? | Understanding covenant election |

Sources: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Book of Moses Essay Series (Interpreter Foundation)

| File | Content Focus |

|---|---|

| 01_Week_Overview | This overview document |

| 02_Historical_Cultural_Context | Ancient Near Eastern covenant practices, Mesopotamian religion, patriarchal culture |

| 03_Key_Passages_Study | Detailed analysis of key verses with cross-references |

| 04_Word_Studies | Hebrew terms: berith (covenant), zera' (seed), kohen (priest), tsedeq (righteousness) |

| 05_Teaching_Applications | Personal study, family, Sunday School, Seminary applications |

| 06_Study_Questions | Questions for individual and group study |

File Status: Complete Created: January 20, 2026 Last Updated: January 20, 2026 Next File: 02_Historical_Cultural_Context.md

Time Period and Geographic Setting

| Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Period | ~2000–1800 BC (Middle Bronze Age) |

| Biblical Era | Patriarchal Period |

| Genealogical Position | Abraham descended from Shem through the line of Genesis 11 |

| Key Transition | From primeval history to patriarchal narratives |

| Geographic Focus | Mesopotamia → Canaan → Egypt |

| Location | Modern Name/Region | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Ur of the Chaldees | Tell el-Muqayyar, southern Iraq | Abraham's birthplace; major Sumerian city |

| Haran | Harran, southeastern Turkey | Abraham's family settled here; major trading center |

| Shechem | Nablus area, West Bank | First altar Abraham built in Canaan |

| Bethel | Near modern Beitin, West Bank | Second altar; "House of God" |

| Hebron/Mamre | al-Khalil, West Bank | Abraham's primary residence; Sarah's burial |

| Salem (Jerusalem) | Jerusalem | Melchizedek's city |

| Egypt | Northeast Africa | Abraham's sojourn during famine |

Political Context

The early second millennium BC was a period of movement and migration across the Fertile Crescent. The Amorite migrations brought Semitic-speaking peoples from the Syrian steppe into Mesopotamia and Canaan. The region had no unified empire—Canaan consisted of independent city-states, Egypt was recovering from the First Intermediate Period, and Mesopotamia was divided among competing kingdoms.

Abraham's travels reflect this era's mobility. His journey from Ur to Haran to Canaan followed established trade routes. His dealings with various kings (the Pharaoh of Egypt, the kings of Sodom, Gomorrah, and Salem) reflect the political fragmentation of the time.

Covenant-Making Rituals

The ceremony described in Genesis 15:9–17, where animals were divided and God passed between them as "a smoking furnace and a burning lamp," reflects ancient covenant-making practices. In the ANE, covenant partners would pass between divided animals, symbolically invoking the fate of the animals upon themselves if they broke the covenant.

Significance: What's remarkable is that only God passed between the animals—not Abraham. This was a unilateral covenant; God bound Himself unconditionally. The Hebrew idiom is karat berith (כָּרַת בְּרִית), literally "to cut a covenant." Jeremiah 34:18–20 explicitly connects covenant breaking with the fate of the divided animals.

Adoption, Surrogate Motherhood, and Circumcision

Adoption and Heir Designation

In ancient Mesopotamia, childless couples could adopt an heir, often a servant. Legal texts from Nuzi (15th century BC) show similar practices to what we see with Abraham and Eliezer. The adopted son would inherit unless a natural heir was later born. Abraham's concern about Eliezer of Damascus becoming his heir (Genesis 15:2–4) reflects actual legal practice.

Surrogate Motherhood

Ancient Near Eastern marriage contracts sometimes stipulated that a barren wife could provide a slave woman to bear children on her behalf. Sarah's giving Hagar to Abraham (Genesis 16:1–4) was not Abraham's idea or a moral failing—it followed accepted cultural practice.

Circumcision

Circumcision was practiced in Egypt and among various Semitic peoples, though typically at puberty as an initiation rite. Infant circumcision as a covenant sign was distinctive to Israel. By instituting circumcision in infancy rather than at puberty, God distinguished Israelite practice from neighboring cultures.

Religious Context of Surrounding Cultures

Mesopotamian Religion: Abraham came from Ur, a major center of moon worship. The moon god Sin (Sumerian: Nanna) was the patron deity of Ur. His father Terah's name may derive from yeraḥ (moon), suggesting family involvement in lunar worship. Abraham 1 confirms that Abraham's family had "turned from their righteousness" to idol worship.

Canaanite Religion: Canaan was home to the worship of El (the high god), Baal (storm god), and various fertility deities. The "terebinth of Moreh" at Shechem (Genesis 12:6) was likely a sacred tree associated with Canaanite religion. By building an altar to YHWH at these locations, Abraham was establishing the worship of the true God in the land.

Egyptian Religion: During Abraham's sojourn in Egypt (Genesis 12:10–20), he encountered a polytheistic culture with elaborate temples and priesthoods. The facsimiles in the Book of Abraham depict Egyptian religious contexts.

Contrast with Israelite Worship:

- One God vs. Many: Abraham worshipped the one true God amid polytheistic cultures

- Ethical Monotheism: YHWH demanded moral righteousness, not just ritual

- Covenant Relationship: Unlike capricious ANE deities, YHWH bound Himself to His people

- No Images: Abraham built altars but no idols, contrasting with surrounding image-based worship

Family Structure

Patriarchal society centered on the beit av (father's house). Abraham's household was large enough to muster 318 trained servants for battle (Genesis 14:14)—indicating substantial wealth and a household of perhaps 1,000+ people.

Economic Realities

Abraham was a semi-nomadic herdsman, also "very rich in cattle, in silver, and in gold" (Genesis 13:2). His refusal of spoils from the king of Sodom (Genesis 14:22–23) shows his desire that God alone be credited as the source of his prosperity.

Women's Roles

Sarah held significant status as Abraham's primary wife. Her barrenness was a source of shame in the culture, yet she was Abraham's partner in the covenant—God changed her name too (Genesis 17:15). Hagar's story shows the vulnerability of servants but also God's compassion—He heard her and blessed her son.

This section highlights details in the Book of Abraham confirmed by ancient texts discovered AFTER Joseph Smith's time.

| Detail in Abraham | Ancient Parallel | Discovery Date |

|---|---|---|

| Human sacrifice in Ur connected to Egyptian religious influence | Egyptian presence in Mesopotamia during Middle Bronze Age | 20th century archaeological discoveries |

| Abraham's father Terah involved in idol worship | Terah's name possibly derived from yeraḥ (moon); Ur was moon-god cult center | Ur excavations 1922–1934 |

| "Plain of Olishem" near Ur | Possible connection to Ulisum/Ulishum in Eblaite texts | Ebla texts discovered 1974–1976 |

| Attempted sacrifice on a lion couch altar | Lion couch imagery in Egyptian funerary and religious contexts | Ongoing Egyptological research |

Sources: John Gee, "An Introduction to the Book of Abraham" (Deseret Book/RSC); Hugh Nibley, "Abraham in Egypt" (Deseret Book)

| Discovery | Date Found | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Ur excavations | 1922–1934 | Revealed Ur as a sophisticated city with ziggurats and moon worship |

| Nuzi tablets | 1925–1931 | Legal customs parallel Abraham's story (adoption, surrogate motherhood) |

| Ebla archives | 1974–1976 | Ancient Semitic names and possible geographic references |

| Mari tablets | 1933–present | Amorite culture contemporary with Abraham |

Important Cautions: We have no direct extra-biblical evidence of Abraham himself. Faith complements historical inquiry—the patriarchal narratives present theological truth regardless of what archaeology can or cannot confirm.

Midrash Genesis Rabbah contains extensive traditions about Abraham:

- Abraham's father Terah was an idol-maker

- Young Abraham smashed his father's idols and was thrown into a furnace by Nimrod

- Abraham's recognition of the one true God through observing nature

These traditions parallel elements in Abraham 1, though Joseph Smith could not have known the full range of rabbinic traditions.

Jewish Liturgical Use: Abraham is remembered daily in Jewish prayer. The Amidah (standing prayer) begins: "Blessed are You, LORD our God and God of our fathers, God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob."

The JST Genesis 14:25–40 reveals extensive material about Melchizedek unknown from the KJV text. Joseph Smith taught that the Melchizedek Priesthood was so named "because Melchizedek was such a great high priest" and to avoid frequent repetition of the name of the Supreme Being.

President Russell M. Nelson has emphasized the covenant path and Abraham as the exemplar of covenant living: "God's everlasting covenant with Abraham... is the same covenant that God offers to each of us today."

Elder D. Todd Christofferson: "The blessings of the Abrahamic covenant are available to all who will come unto the Lord and keep His commandments."

This week marks a dramatic transition in the biblical narrative—from the primeval history of creation, fall, flood, and scattering to the intimate story of one family chosen to bless all the earth. We meet Abraham, a man born into an idolatrous culture who desired "to be a greater follower of righteousness" (Abraham 1:2).

| Chapter | Summary |

|---|---|

| Abraham 1 | Abraham's background: his family's idolatry, his near-sacrifice, God's deliverance |

| Abraham 2 | The Abrahamic covenant in fullness; Abraham's journey to Canaan; sojourn in Egypt |

| Genesis 12 | God's call to Abram; covenant promises; altars at Shechem and Bethel; Egypt sojourn |

| Genesis 13 | Separation from Lot; covenant promise of land renewed; altar at Hebron |

| Genesis 14 | War of the kings; Abram rescues Lot; meets Melchizedek; pays tithes; refuses spoils |

| Genesis 15 | Covenant ceremony with divided animals; promise of innumerable seed; Abram counted righteous |

| Genesis 16 | Hagar and Ishmael; God hears Hagar in the wilderness |

| Genesis 17 | Circumcision covenant; name changes (Abram→Abraham, Sarai→Sarah); promise of Isaac |

Major Themes This Week

- The Abrahamic Covenant — The foundational covenant pattern for all God's dealings with humanity

- Righteous Desires Amid Wickedness — Personal righteousness possible regardless of family background

- Faith Counted as Righteousness — Abraham's belief in seemingly impossible promises

- Melchizedek and the Priesthood — The mysterious king-priest and type of Christ

- Covenant Names and Identity — Name changes signify covenant transformation

"1 Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee:

2 And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing:

3 And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee: and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed." — Genesis 12:1–3

Literary Structure and Hebrew Insights

The command lekh-lekha (לֶךְ־לְךָ, "go forth" or "go to yourself") contains a linguistic intensification. The doubling suggests "go for yourself" or "go to your true self"—this journey will reveal Abraham's identity. This phrase appears only twice in Torah: here and at the Akedah (Gen. 22:2)—both moments of radical obedience.

The seven "I will" statements in verses 2–3 signal covenant completeness:

- I will make of thee a great nation

- I will bless thee

- [I will] make thy name great

- Thou shalt be a blessing

- I will bless them that bless thee

- [I will] curse him that curseth thee

- In thee shall all families of the earth be blessed

barak (H1288) — "Bless," appears five times. The shift from passive ("I will bless thee") to active ("thou shalt be a blessing") is crucial—Abraham receives blessing to give blessing.

shem (H8034) — "Name." "I will make thy name great" contrasts with Babel's "let us make us a name" (Gen. 11:4). At Babel, humans seized renown; with Abraham, God bestows it.

mishpachah (H4940) — "Families." "All families of the earth"—universal scope reversing Babel's scattering.

Doctrinal Analysis and Cross-References

The Nature of Divine Calling: God calls; humans respond. Abraham didn't choose God; God chose Abraham. Separation from worldly systems is often required. Faith precedes sight—"a land that I will shew thee."

The Missionary Dimension: The ultimate promise—"in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed"—transforms Abraham's calling from personal blessing to universal mission. Abraham 2:11 clarifies: "all the families of the earth [shall] be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal."

| Reference | Connection |

|---|---|

| Hebrews 11:8 | "By faith Abraham, when he was called... obeyed; and he went out, not knowing whither he went" |

| Galatians 3:8 | "The scripture... preached before the gospel unto Abraham" |

| 1 Nephi 15:18 | Abraham's seed = those who accept Christ and keep commandments |

| D&C 84:34 | "They become the sons of Moses and of Aaron and the seed of Abraham" |

"2 And, finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers, and the right whereunto I should be ordained to administer the same; having been myself a follower of righteousness, desiring also to be one who possessed great knowledge, and to be a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge, and to be a father of many nations, a prince of peace, and desiring to receive instructions, and to keep the commandments of God, I became a rightful heir, a High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers." — Abraham 1:2

Analysis

The passage exhibits climactic parallelism—Abraham was already "a follower of righteousness" but desired to be "a GREATER follower of righteousness." He already possessed knowledge but desired "GREATER knowledge." "Fathers" appears 7 times in verses 2–4. "Desiring" appears 3 times. "Greater" appears 3 times.

The Hebrew equivalent of "follower of righteousness" would be rodef tsedeq (רֹדֵף צֶדֶק)—literally "pursuer of righteousness." The verb radaf means to chase, pursue, follow hard after. This isn't passive acquiescence but active pursuit.

Joseph Smith's Parallel: Abraham's situation parallels Joseph Smith's. Both lived in religiously confused environments, both questioned family traditions, both sought truth directly from God. Like Abraham, Joseph desired greater knowledge, sought the blessings of the fathers (priesthood), and became a rightful heir.

Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught: "Righteous desires need to be relentless... 'the men and women, who desire to obtain seats in the celestial kingdom, will find that they must battle every day'" (Ensign, Nov. 1996).

"9 And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee above measure, and make thy name great among all nations, and thou shalt be a blessing unto thy seed after thee, that in their hands they shall bear this ministry and Priesthood unto all nations;

10 And I will bless them through thy name; for as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed, and shall rise up and bless thee, as their father;

11 And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse them that curse thee; and in thee (that is, in thy Priesthood) and in thy seed (that is, thy Priesthood), for I give unto thee a promise that this right shall continue in thee, and in thy seed after thee (that is to say, the literal seed, or the seed of the body) shall all the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal." — Abraham 2:9–11

"1 And when Abram was ninety years old and nine, the Lord appeared to Abram, and said unto him, I am the Almighty God; walk before me, and be thou perfect. 2 And I will make my covenant between me and thee, and will multiply thee exceedingly... 5 Neither shall thy name any more be called Abram, but thy name shall be Abraham; for a father of many nations have I made thee... 7 And I will establish my covenant between me and thee and thy seed after thee in their generations for an everlasting covenant, to be a God unto thee, and to thy seed after thee." — Genesis 17:1–8

Four Pillars of the Covenant

- Land — "All the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession" (Gen. 17:8). The temporal land of Canaan pointed to eternal inheritance.

- Seed/Posterity — "I will multiply thee exceedingly" (Gen. 17:2). Includes literal/biological seed, adopted/spiritual seed ("as many as receive this Gospel"), and eternal seed (D&C 132:19–20).

- Priesthood — "In thy Priesthood... shall all the families of the earth be blessed" (Abr. 2:11). Abraham 2 clarifies that the covenant centers on priesthood authority.

- Gospel Blessings — "All the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal" (Abr. 2:11). The missionary dimension.

Hebrew Insights

berith (H1285) — "Covenant." Appears 11 times in Genesis 17 alone. Not merely a contract but a divine decree which God establishes and humans accept.

Avraham (H85) — From Abram (אַבְרָם, "exalted father") to Abraham (אַבְרָהָם, "father of a multitude"). The added ה (heh) is from God's name יהוה (YHWH)—God inserted part of His own name into Abraham's.

'olam (H5769) — "Everlasting." From root 'alam (to hide, conceal)—the hidden time, beyond mortal sight. "Everlasting covenant" (berith 'olam).

tamim (H8549) — "Perfect." Complete, whole, blameless—not sinless perfection but wholehearted devotion.

Cross-References

| Reference | Connection |

|---|---|

| Galatians 3:7–9, 29 | "They which are of faith... are the children of Abraham... heirs according to the promise" |

| 3 Nephi 20:25–27 | "Ye are the children of the covenant" |

| D&C 84:33–34 | "They become... the seed of Abraham... the elect of God" |

| D&C 132:19, 29–32 | "Then shall they be gods... to their exaltation and glory in all things" |

"18 And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God. 19 And he blessed him, and said, Blessed be Abram of the most high God, possessor of heaven and earth: 20 And blessed be the most high God, which hath delivered thine enemies into thy hand. And he gave him tithes of all." — Genesis 14:18–20

"26 Now Melchizedek was a man of faith, who wrought righteousness; and when a child he feared God, and stopped the mouths of lions, and quenched the violence of fire. 27 And thus, having been approved of God, he was ordained an high priest after the order of the covenant which God made with Enoch, 28 It being after the order of the Son of God..." — JST Genesis 14:25–40

Analysis and Type of Christ

| Melchizedek | Jesus Christ |

|---|---|

| King of Righteousness (name meaning) | "The LORD Our Righteousness" (Jer. 23:6) |

| King of Salem/Peace (Heb. 7:2) | Prince of Peace (Isa. 9:6) |

| Priest of the Most High God | Great High Priest (Heb. 4:14) |

| No recorded genealogy (Heb. 7:3) | Eternal Son of God |

| Both king and priest | Priest-King (Zech. 6:13) |

| Blessed Abraham | Blesses all who come to Him |

| Received tithes from Abraham | Receives our offerings |

JST Genesis 14:30–31 describes priesthood powers: to break mountains, divide seas, dry up waters, put at defiance armies of nations, stand in the presence of God—all "by faith" and "by the will of the Son of God which was from before the foundation of the world."

Alma 13:17–18 adds: "Melchizedek having exercised mighty faith... did preach repentance unto his people. And behold, they did repent; and Melchizedek did establish peace in the land in his days."

Hebrew Insights

מַלְכִּי־צֶדֶק (H4442) — Malki-Tsedeq, compound: malki (my king) + tsedeq (righteousness). Meaning: "My king is righteousness" or "King of Righteousness."

שָׁלֵם (H8004) — Shalem, related to shalom (שָׁלוֹם)—peace. Psalm 76:2: "In Salem also is his tabernacle"—identified with Jerusalem.

אֵל עֶלְיוֹן — El 'Elyon, "God Most High." Appears four times in Genesis 14:18–22. Abraham identifies El 'Elyon with YHWH (Gen. 14:22).

מַעֲשֵׂר (H4643) — Ma'aser, "tithe, tenth part." First mention of tithing in scripture.

"1 After these things the word of the Lord came unto Abram in a vision, saying, Fear not, Abram: I am thy shield, and thy exceeding great reward.

5 And he brought him forth abroad, and said, Look now toward heaven, and tell the stars, if thou be able to number them: and he said unto him, So shall thy seed be.

6 And he believed in the Lord; and he counted it to him for righteousness." — Genesis 15:1–6

Analysis: Faith Counted as Righteousness

This verse is quoted more often in the New Testament than almost any OT verse outside the Psalms. Abraham could have doubted—he was 75 when called, childless, married to a barren wife. Every year without Isaac could have weakened faith. But "he staggered not at the promise of God through unbelief" (Romans 4:20).

Hebrew Insights:

- he'emin (H539) — "He believed." Root: 'aman—to be firm, steady, trustworthy. Related to 'amen. Active trust, not passive intellectual assent.

- chashav (H2803) — "Counted/reckoned." An accounting term—to credit to an account. God credited righteousness to Abram's account based on faith.

- tsedaqah (H6666) — "Righteousness." Right standing before God, conformity to His will.

- magen (H4043) — "Shield." God Himself is Abram's defense.

Faith and Works Cooperate: Genesis 15:6 says Abraham's faith was counted as righteousness. James 2:21–23 says Abraham was "justified by works, when he had offered Isaac." The resolution: Abraham's faith in Genesis 15 was later demonstrated by obedience in Genesis 22. Faith initiates righteousness; works perfect it. 2 Nephi 25:23: "We know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do."

Cross-References

| Reference | Connection |

|---|---|

| Romans 4:1–25 | Entire chapter on Abraham's faith counted as righteousness |

| Galatians 3:6–9 | "Abraham believed God... they which are of faith, the same are the children of Abraham" |

| Hebrews 11:8–12 | "By faith Abraham... through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive" |

| James 2:21–24 | "Was not Abraham our father justified by works... faith wrought with his works" |

| Moroni 10:32 | "Come unto Christ... then is his grace sufficient for you" |

Genesis 12:6–7 — "Unto thy seed will I give this land"

Abram's first action in Canaan was to build an altar to the LORD at Shechem. God appeared and reaffirmed the promise. The "plain of Moreh" (Moreh means "teacher" or "oracle") may be the same location where Jacob later bought property and Joshua renewed the covenant (Joshua 24:25–26).

Genesis 13:5–12 — Abram and Lot Separate

When conflict arose, Abram—the elder and patriarch—gave Lot first choice. Lot "lifted up his eyes" and chose the well-watered Jordan valley near Sodom. Abram's selfless peacemaking contrasts with Lot's selfish choice. Jesus taught, "Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God" (Matthew 5:9).

Genesis 14:21–24 — "I will not take from a thread even to a shoelatchet"

Abram refused spoils from the king of Sodom: "lest thou shouldest say, I have made Abram rich." Abram gave to God (tithes to Melchizedek) but refused from worldly kings. Jesus taught, "Ye cannot serve God and mammon" (Matthew 6:24).

Genesis 16:7–13 — "Thou God seest me"

Hagar named the LORD "El Roi" (אֵל רֳאִי)—"Thou God seest me." God sees and cares for the marginalized and afflicted. Ishmael's name means "God hears." The well was called "Beer-lahai-roi"—"Well of the Living One Who Sees Me."

Genesis 17:9–14 — Circumcision as Covenant Sign

The covenant "sign" ('ot, אוֹת) parallels the rainbow sign of the Noahic covenant and the Sabbath sign of the Mosaic covenant. Paul taught that physical circumcision is superseded by "circumcision of the heart" (Romans 2:29)—inward covenant commitment symbolized by baptism and temple ordinances.

Genesis 17:15–17 — Abraham Laughed

God changed Sarai's name to Sarah and promised she would bear a son. Abraham "fell upon his face, and laughed" (v. 17)—joy mixed with incredulity. The name "Isaac" (Yitschaq, יִצְחָק) means "he laughs." Luke 1:37: "With God nothing shall be impossible."

Genesis 17:23–27 — Immediate Obedience

"In the selfsame day" Abraham circumcised himself (at age 99!), Ishmael, and all males in his household. No delay, no excuses—instant covenant compliance. James 1:22: "Be ye doers of the word, and not hearers only."

Hebrew: בְּרִית (berith) | Strong's: H1285 | Pronunciation: beh-REET

Root: Possibly related to barah (בָּרָה, H1262) — "to cut, to select food"

Definition: Covenant, alliance, pledge. Between men: treaty, alliance, agreement. Between God and man: covenant, compact. The Hebrew idiom is karat berith (כָּרַת בְּרִית) — literally "to cut a covenant," from the ancient ritual of dividing animals and passing between the pieces (Genesis 15:9–18).

OT Occurrences: 287 times. In Genesis 17, the word berith appears 11 times (vv. 2, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 19, 21).

Greek (LXX): διαθήκη (diathēkē, G1242) — testament, will. The translators chose diathēkē (unilateral disposition) over synthēkē (mutual contract), emphasizing that God's covenant is His gracious initiative, not a negotiated agreement.

Latin (Vulgate): foedus (treaty) and testamentum (testament). Root of English "federal" and "testament."

Theological Significance: The Abrahamic covenant is the foundational covenant in scripture. All subsequent covenants build on it: Mosaic, Davidic, and New Covenant. The covenant is relational, not transactional—God binds Himself to Abraham and his seed in perpetual relationship.

| Covenant | Contract |

|---|---|

| Based on relationship | Based on transaction |

| Involves whole persons | Involves specific services |

| Usually permanent | Usually temporary |

| Requires faithfulness | Requires performance |

Hebrew: זֶרַע (zera') | Strong's: H2233 | Pronunciation: ZEH-rah

Root: zara (זָרַע, H2232) — "to sow, scatter seed"

Semantic Range: Physical seed for planting, semen, offspring, descendants, future generations. Zera' appears 17 times in Genesis 12–17.

Greek (LXX): σπέρμα (sperma, G4690). Paul exploits the collective singular: "Now to Abraham and his seed were the promises made. He saith not, And to seeds, as of many; but as of one, And to thy seed, which is Christ" (Galatians 3:16).

Dual Meaning: Abraham 2:10 clarifies: "as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed." Abraham's seed includes (1) literal/biological—Isaac, Jacob, the twelve tribes, (2) spiritual/adoptive—all who receive the gospel, and (3) eternal—eternal increase (D&C 132:30).

Hebrew: צְדָקָה (tsedaqah) | Strong's: H6666 | Pronunciation: tsed-ah-KAH

Root: tsadaq (צָדַק, H6663) — "to be just, righteous"

Semantic Range: Legal (justice), moral (uprightness), relational (right standing with God), salvific (God's saving intervention), covenantal (faithfulness to obligations).

Pivotal Verse: Genesis 15:6 — "He believed in the LORD; and he counted it to him for righteousness." The verb chashav (H2803) is a bookkeeping term—to credit to an account. God credited tsedaqah to Abraham's account based on his faith ('aman).

Greek (LXX): δικαιοσύνη (dikaiosynē, G1343). Paul quotes Genesis 15:6 repeatedly: Romans 4:3, Galatians 3:6, James 2:23.

LDS Perspective: Righteousness is both imputed (credited by grace through faith) and imparted (given through sanctification). Faith initiates; works perfect. Moroni 10:32–33: "Come unto Christ... then is his grace sufficient for you, that by his grace ye may be perfect in Christ."

Hebrew: מַלְכִּי־צֶדֶק (Malki-Tsedeq) | Strong's: H4442

Components: מֶלֶךְ (melek, "king") + צֶדֶק (tsedeq, "righteousness"). Literal meaning: "My king is righteousness" or "King of Righteousness." Hebrews 7:2 translates it: "King of righteousness."

OT Occurrences: Only 2 times — Genesis 14:18 and Psalm 110:4.

NT Development: Hebrews 7 devotes an entire chapter to Melchizedek as a type of Christ: no genealogy, eternal priesthood, greater than Abraham, greater than Levi.

D&C 107:1–4: "The Melchizedek Priesthood holds the right of presidency... It was called the Holy Priesthood, after the Order of the Son of God. But out of respect or reverence to the name of the Supreme Being... they called that priesthood after Melchizedek."

Hebrew: כֹּהֵן (kohen) | Strong's: H3548 | Pronunciation: ko-HAYN

Definition: Priest, one who officiates at the altar. Used for patriarchal priests (Melchizedek), Levitical priests (Aaron), and pagan priests. OT occurrences: 750 times.

This Week: The only use is Genesis 14:18 — "priest of the most high God." This predates the Aaronic priesthood by centuries, demonstrating that priesthood authority existed from the beginning.

Greek (LXX): ἱερεύς (hiereus, G2409). Christ as high priest: Hebrews 4:14. Believers as priests: 1 Peter 2:9, Revelation 1:6.

| Hebrew | Term | Meaning | Key Passage |

|---|---|---|---|

| אַבְרָהָם | Avraham (H85) | "Father of a multitude." God inserted ה (heh) from His own name YHWH into Abram's name. | Genesis 17:5 |

| שָׂרָה | Sarah (H8283) | "Princess." Changed from Sarai ("my princess") — universal, not possessive. | Genesis 17:15 |

| מַעֲשֵׂר | Ma'aser (H4643) | "Tenth part, tithe." First mention of tithing in scripture. | Genesis 14:20 |

| אֵל שַׁדַּי | El Shaddai (H7706) | "God Almighty." Power to do the impossible—giving a son to 90-year-old Sarah. | Genesis 17:1 |