| Church Manuals | |

| Come Follow Me Manual | — |

| Scripture Helps | View |

| OT Seminary Teacher Manual | View |

| OT Institute Manual | View |

| Pearl of Great Price Manual | View |

| Scripture Reference | |

| Bible Dictionary | View |

| Topical Guide | View |

| Guide to the Scriptures | View |

| Church Media | |

| Gospel for Kids | View |

| Bible Videos | View |

| Church Publications & Library | |

| Church Magazines | View |

| Gospel Library | View |

Zion — The City of Enoch

5-Minute Overview

You'll spend an entire week in one of the most remarkable chapters the Restoration has given us. Moses 7 takes Enoch from a reluctant prophet who calls himself 'but a lad' to a seer who beholds all of history. You'll encounter one of the most theologically daring images in scripture — God weeping — and wrestle with why an omnipotent Being chooses to feel sorrow. You'll watch Enoch's people become so unified in righteousness that they're called 'Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind,' and then see the entire city taken into heaven.

Official Church Resources

Video Commentary

Specialized Audiences

Reference & Study Materials

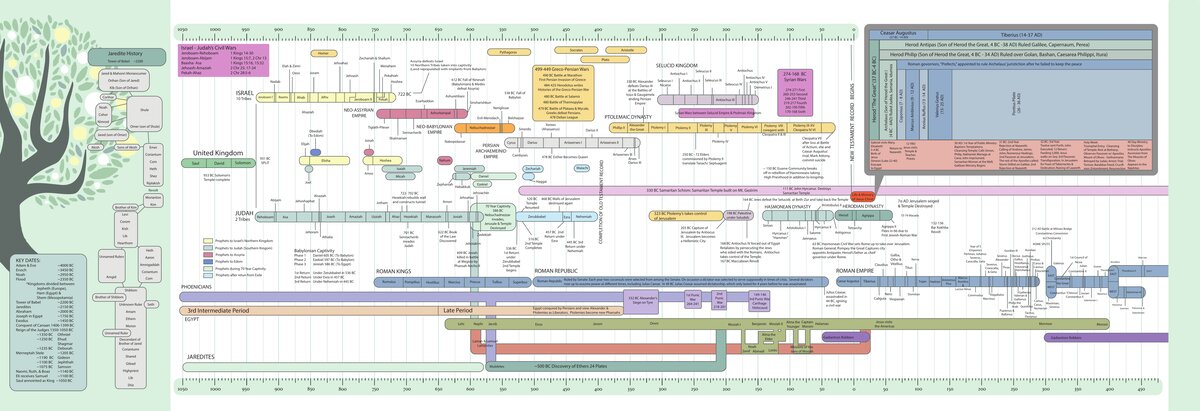

Last week we explored the remarkable claim in Moses 6 that writing itself was a divine gift—a "pure and undefiled" language given to Adam and his descendants. We traced the alphabet's origins from Proto-Sinaitic pictographs through Paleo-Hebrew to the Aramaic script used today. This week we are going to build on that foundation and introduce the vowels, a little about their history, and explore how they work.

We will combine this with this week's reading of Moses 7—one of the most remarkable chapters in all of Restoration scripture. Where Genesis offers only four cryptic verses about Enoch ("Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him" — Genesis 5:24), Moses 7 expands this into 69 verses of prophetic vision spanning from the antediluvian world to the Second Coming.

Later in this lesson, we'll examine ancient documents discovered long after Joseph Smith's death—texts he could not have read, in languages he did not know, from manuscripts that had not yet been found. What Joseph revealed in 1830 continues to find remarkable validation in these discoveries, and the parallels run both ways: ancient texts illuminate our scripture, while our scripture provides context that scholars lack.

But first, let's continue building our Hebrew foundation.

Why We're Introducing Hebrew

You may have noticed that these Weekly Insights include lessons on the Hebrew language. This is intentional. One of our goals this year is to help you gain enough familiarity with Hebrew that you can begin to access the Hebrew Bible on its own terms—using lexicons, concordances, and study tools to discover meanings that don't always come through in translation.

We're not trying to make you fluent. We're trying to give you enough foundation that when you encounter a Hebrew word in your study, you can look it up, understand its root, and see how it connects to other biblical concepts. The scriptures were written in Hebrew for a reason. The more we understand that original language, the more the text opens up to us.

Last week we introduced the 22 consonants of the Hebrew alphabet. This week we continue with the vowel system—both the ancient "mother letters" that hint at vowels and the medieval Masoretic dots and dashes that preserve traditional pronunciation. These tools will serve you throughout this year's study.

In this lesson, we are going to examine some things that are genuinely astonishing about Moses 7. The parallels between this revealed text and ancient documents discovered long after Joseph Smith's death are not vague or general—they are specific, detailed, and increasingly difficult to explain away.

But before we examine these parallels, we need to understand what these ancient documents actually are. Many Latter-day Saints have never heard of them.

1 Enoch (Ethiopian Enoch) — A collection of apocalyptic writings attributed to Enoch, preserved in the Ethiopian Orthodox canon. It contains elaborate visions of heaven, the fall of the "Watchers" (rebellious angels), the coming judgment, and a messianic figure called the "Son of Man." While portions were known to early Christians (Jude 14-15 quotes it directly), the complete text wasn't available in English until Richard Laurence's translation in 1821—and even then, it was an obscure scholarly work virtually unknown in frontier America. (Alternative scholarly translation at CCEL)

2 Enoch (Slavonic Enoch) — A separate Enoch text preserved only in Old Church Slavonic manuscripts. It describes Enoch's ascent through seven heavens, his transformation into an angelic being, and his being "clothed with glory." The first English translation appeared in 1896—66 years after Joseph Smith dictated Moses 7. (Scholarly background at Marquette University)

3 Enoch (Hebrew Enoch) — A Jewish mystical text describing Enoch's transformation into the angel Metatron and his enthronement in heaven. Not translated into English until Hugo Odeberg's 1928 scholarly edition.

The Book of Giants — Fragments discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran in 1948. This text expands on the Genesis 6 account of the Nephilim (giants), describing their dreams, their awareness of coming judgment, and the earth mourning because of their wickedness. Joseph Smith died 104 years before these fragments were discovered. (View original fragments at the Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library)

Midrash Rabbah and Zohar — Jewish rabbinic commentaries and mystical texts containing traditions about Enoch and God's emotional response to human wickedness. These were not available in English in 1830 and would have required knowledge of Hebrew and Aramaic to access.

The question scholars must grapple with: How did an uneducated frontier farmer produce a text in 1830 that matches documents he could not have read, in languages he did not know, from manuscripts that had not yet been discovered?

With that background, consider what Joseph Smith could not have known in 1830:

| Detail in Moses 7 | Ancient Parallel | Discovery Date |

|---|---|---|

| God weeps (7:28-29) | 1 Enoch, Midrash Rabbah, Zohar | Not available in English 1830 |

| Earth as "mother of men" crying out (7:48) | Book of Giants (Qumran) | Discovered 1948 |

| Enoch receives "right to throne" (7:59) | Nineveh tablet, 3 Enoch | Not translated until 20th century |

| Enoch "clothed with glory" (7:3) | 2 Enoch 22:8-10 | First English translation 1896 |

| Giants "stood afar off" (7:15) | Book of Giants: righteous on "skirts of four huge mountains" | Discovered at Qumran 1948 |

When renowned Aramaic scholar Matthew Black was confronted with these parallels, Hugh Nibley reported that it "really staggered him." Black's response? "Well, someday we will find out the source that Joseph Smith used."

No such source has ever been found. And 195 years of scholarship have only strengthened the case that Moses 7 contains authentic ancient material.

Moses 7 presents five themes that together constitute one of the most theologically profound chapters in all scripture:

Key Themes Emerging:- The Weeping God—divine emotion and the nature of Godhood

- The Definition of Zion—one heart, one mind, no poor among them

- Collective Translation—an entire city removed to heaven

- Panoramic Vision—from the Flood to the Second Coming

- The Earth as Mother—a speaking, suffering, covenantal being

Perhaps no passage in Restoration scripture more directly challenges traditional Christian theology than Moses 7:28–37.

The doctrine of divine impassibility—that God cannot suffer, change, or be affected by His creatures—had been a cornerstone of classical theism since the Church Fathers merged biblical revelation with Greek philosophical categories. Augustine, Anselm, and Thomas Aquinas all affirmed that God is "without passions in the proper sense."

Enoch's question to God perfectly articulates this classical position:

"How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity? And were it possible that man could number the particles of the earth, yea, millions of earths like this, it would not be a beginning to the number of thy creations; and thy curtains are stretched out still; and yet... the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains?" (Moses 7:29–31)

How can a Being so vast, so eternal, so holy, be moved to tears by creatures so small?

God does not deny His weeping or explain it away as anthropomorphism. Instead, He reveals the reason:

"Behold these thy brethren; they are the workmanship of mine own hands, and I gave unto them their knowledge, in the day I created them; and in the Garden of Eden, gave I unto man his agency; And unto thy brethren have I said, and also given commandment, that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood." (Moses 7:32–33)

The theological implications are profound. God's weeping is not weakness but love. A God who cannot grieve cannot truly love—love requires vulnerability to the beloved.

This connects directly to Week 05's teaching on the Fall and agency (Moses 6:48–56). The same agency that enables progression also enables rebellion. God cannot give agency without accepting that some will use it to choose misery. His weeping is the consequence of love that grants genuine freedom.

While Moses 7's weeping God has no parallel in the Bible, it appears prominently in ancient Jewish and early Christian sources unknown to Joseph Smith:

Midrash Rabbah on Lamentations: God Himself weeps at the destruction of the temple. When the angels try to stop Him, God replies: "If thou lettest Me not weep now, I will repair to a place which thou hast not permission to enter, and will weep there." 1 Enoch (Book of Parables): Enoch "wept bitterly" over wickedness, and heaven joins in his sorrow. Zohar: A full "chorus of weeping" begins with the Messiah and expands to include all heaven.As Hugh Nibley observed: "There is, to say the least, no gloating in heaven over the fate of the wicked world."

Moses 7:18 provides the scriptural definition that shapes Latter-day Saint understanding of Zion:

"The Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them."

Notice what Zion is not in this definition. It is not primarily a geographical location, a political system, or even a temple. Zion is a people characterized by three qualities:

The Hebrew concept involves levav (לֵבָב)—the heart as seat of will and emotion—united in communal purpose. This is not uniformity that erases individuality but unity of covenant, purpose, and mutual love.

The early Church in Acts achieved something similar: "the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul" (Acts 4:32). The Nephites after Christ's visit "were in one, the children of Christ" (4 Nephi 1:17).

The Hebrew tsedaqah (צְדָקָה) implies right relationship—with God and with each other. Zion righteousness is not merely personal piety but covenantal fidelity that shapes community life.

This phrase echoes Deuteronomy 15:4—"there shall be no poor among you"—which describes the result of faithful observance of sabbatical year and jubilee laws. In Enoch's Zion, this equality came through consecration.

President Brigham Young frequently referenced this verse: "We should have no poor; we should all be alike partakers of the good things of this world" (Journal of Discourses 19:47).

The translation of Enoch's city presents a remarkable doctrine: "Zion, in process of time, was taken up into heaven" (Moses 7:21).

This was not merely Enoch's individual translation (as recorded in Genesis 5:24) but the collective translation of an entire community.

The phrase "in process of time" is significant. Translation was not instantaneous but gradual—the community grew in righteousness until reaching a threshold that qualified them for removal from the terrestrial sphere. Joseph Smith taught that translated beings inhabit "a place prepared for such characters... of the terrestrial order" (Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 170), serving as "ministering angels unto many planets."

While individual translation (Enoch, Elijah) appears across cultures, the translation of an entire community is virtually unique to Moses 7. Yet ancient sources hint at this possibility:

Mandaean Enoch Fragments: Describe others besides Enoch ascending bodily with him. Late Midrash: Contains traditions of group ascension with righteous leaders.As David Larsen observes: "Can an entire community ascend to heaven?" Moses 7 answers affirmatively—a concept with few parallels in world literature.

A remarkable feature of Moses 7 is the personification of the earth as a speaking, suffering, covenantal being:

"And it came to pass that Enoch looked upon the earth; and he heard a voice from the bowels thereof, saying: Wo, wo is me, the mother of men; I am pained, I am weary, because of the wickedness of my children. When shall I rest, and be cleansed from the filthiness which is gone forth out of me?" (Moses 7:48)

This is not merely poetic personification. The earth speaks, mourns, and anticipates rest.

This precise motif—the earth as "mother of men" complaining about wickedness—appears nowhere in the Bible. But it does appear in the Book of Giants discovered at Qumran in 1948:

"Through your fornication on the earth, and it (the earth) has [risen up ag]ainst y[ou and is crying out] and raising accusation against you." (4Q203, Frag. 8:6–12)

Andrew Skinner notes three key correspondences:

- Both texts have the earth itself complaining

- Both describe wickedness as "filthiness" or "fornication"

- Both anticipate destruction to cleanse the earth

Moses 7 ends with one of the most tender promises in scripture:

"And the Lord said unto Enoch: Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other." (Moses 7:63)

The embrace imagery suggests intimate reunion after long separation. Two Zion communities—one ancient, one latter-day—embracing after millennia apart. This is not distant, impersonal salvation but reunion, embrace, tears of joy.

This is the ultimate hope of the gathering of Israel.

Last week we introduced the Hebrew alphabet as an abjad—a writing system of 22 consonants with no vowels. We noted that ancient readers supplied vowels from context, much as you can read "rd ths sntnc" as "read this sentence." But this raises an important question: How do we know how to pronounce ancient Hebrew words today?

The answer involves two systems: one ancient, one medieval.

Long before the Masoretes added vowel marks to the biblical text, Hebrew scribes developed a partial solution to the vowel problem. They began using certain consonants to hint at vowel sounds. These consonants came to be called matres lectionis (Latin for "mothers of reading")—letters that "give birth" to vowel sounds.

Three consonants serve as these "mother letters":

| Letter | Hebrew | Name | Consonant Sound | Vowel Hint |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| א | Aleph | אָלֶף | Silent (glottal stop) | Sometimes marks /a/ or /e/ |

| ה | He | הֵא | /h/ | Marks /a/, /e/, or /o/ at word endings |

| ו | Vav | וָו | /v/ or /w/ | Marks /o/ or /u/ |

| י | Yod | יוֹד | /y/ | Marks /i/ or /e/ |

When these letters appear in a word without their consonant sound, they signal a vowel:

Examples:- תּוֹרָה (Torah) — The Vav signals the /o/ sound; the final He is silent, marking the /a/ sound

- הִיא (hi, "she") — The Yod signals the /i/ sound; it's not pronounced as the consonant /y/

- מוֹשֶׁה (Moshe/Moses) — The Vav signals /o/; the final He is silent, marking the /e/ sound

A note on Aleph: While Aleph is traditionally listed among the matres lectionis, it functions differently than the others. In biblical Hebrew, Aleph was not systematically developed as a vowel marker. More often, it appears as a glottal stop, and in modern pronunciations as a silent root consonant (as in רֹאשׁ, rosh, "head," where Aleph is part of the root ר-א-ש) rather than as a letter added purely to indicate a vowel. When Aleph does mark vowels, it typically indicates /a/ sounds, but clear examples are rare and often involve loanwords or foreign names.

This system was never complete—it only hinted at some vowels in some positions. But it helped preserve pronunciation across generations. When you see these letters in Hebrew words and they don't seem to function as consonants, they're likely serving as matres lectionis.

The choice of these letters wasn't arbitrary. They are the "weakest" consonants in Hebrew—produced with the least obstruction of airflow, they naturally blend into vowel sounds:

- Aleph (א) is a glottal stop—barely a consonant at all. It easily fades into the vowel that follows.

- He (ה) is a light breath sound that naturally trails off into the preceding vowel, especially at word endings.

- Vav (ו) as /w/ naturally glides into /o/ or /u/ sounds.

- Yod (י) as /y/ naturally glides into /i/ or /e/ sounds.

Linguists call Vav and Yod semivowels or glides—consonants that hover at the boundary between consonant and vowel. Their dual nature made them perfect candidates for vowel markers.

A historical note: When the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet (closely related to Hebrew) around the 9th century BCE, they had no use for these guttural and glide consonants that didn't exist in Greek. So they repurposed them as dedicated vowel letters: Aleph became Alpha (Α, α), He became Epsilon (Ε, ε), Vav became Upsilon (Υ, υ), and Yod became Iota (Ι, ι). This was a revolutionary innovation—the first true alphabet with full vowel representation. The matres lectionis, then, represent an intermediate stage: Hebrew scribes recognized that these consonants could hint at vowels, but they never took the final step of converting them entirely.

The silent "h" in English: You've likely noticed that many biblical names end with a silent "h"—Leah, Sarah, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Judah, Noah. This reflects the Hebrew final He (ה) being transliterated into English. In Hebrew, this He marks the final vowel sound but is itself silent. When English translators encountered these names, they kept the "h" in the spelling even though it isn't pronounced. So when you see that silent "h" at the end of a biblical name, you're seeing the echos of Hebrew.

Between the 5th and 10th centuries CE, Jewish scholars known as the Masoretes (from masorah, מָסוֹרָה, meaning "tradition") undertook a monumental project: preserving the exact pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible for all time.

By this period, Hebrew was no longer a living spoken language for most Jews. Aramaic, Greek, and later Arabic had become the common tongues. The Masoretes feared that the traditional pronunciation—passed down orally for generations—would be lost forever.

Their solution was brilliant: they invented a system of dots and dashes called niqqud (נִקּוּד, "dotting") that could be placed around the consonants without changing the consonantal text itself. The sacred letters remained untouched; the vowel marks simply floated above, below, and within them.

Three centers of Masoretic activity developed different systems:

| School | Location | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Babylonian | Mesopotamia | 6th–8th c. | Vowels placed above letters; now obsolete |

| Palestinian | Israel | 6th–8th c. | Intermediate system; fragments survive |

| Tiberian | Tiberias, Galilee | 8th–10th c. | Vowels above and below; became the standard |

The Tiberian system eventually won out and is what we see in Hebrew Bibles today. The most authoritative Tiberian manuscript is the Leningrad Codex (1008 CE), which serves as the basis for most modern Hebrew Bible editions.

The Tiberian Masoretes developed a comprehensive system of vowel marks. Here are the primary vowels:

| Name | Symbol | Sound | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qamats | בָ | /a/ as in "father" | בָּרָא (bara, "created") |

| Patach | בַ | /a/ as in "father" | בַּת (bat, "daughter") |

| Tsere | בֵ | /e/ as in "they" | בֵּן (ben, "son") |

| Segol | בֶ | /e/ as in "bed" | מֶלֶךְ (melekh, "king") |

| Chiriq | בִ | /i/ as in "machine" | בִּית (bit, from bayit) |

| Cholem | בֹ | /o/ as in "go" | קֹדֶשׁ (qodesh, "holy") |

| Qibbuts | בֻ | /u/ as in "flute" | קֻדָּשׁ (quddash, "sanctified") |

| Shureq | בּוּ | /u/ as in "flute" | שָׁלוֹם (shalom) |

| Sheva | בְ | very short or silent | בְּרֵאשִׁית (b'reshit) |

Click on the Vowel button above to hear examples of these sounds. Notice how Vav combines with the Cholem dot (בֹּ) to form the full /o/ vowel, and with dagesh (בּוּ) to form shureq (/u/). The matres lectionis system continues to work alongside the Masoretic vowel points.

Let's look at the opening word of Genesis with full Masoretic pointing:

בְּרֵאשִׁית (B'reshit — "In the beginning")Breaking it down:

- בְּ — Bet with sheva (bə) and dagesh (hard /b/)

- רֵ — Resh with tsere (re)

- א — Aleph (root consonant from ר-א-שׁ "head/beginning")

- שִׁ — Shin with chiriq (shi)

- י — Yod (serving as mater lectionis for /i/)

- ת — Tav (t)

Understanding the vowel system helps in several ways:

- Recognizing word roots: Hebrew words built on the same consonantal root (like K-T-B for "writing") will look similar even when vowels differ. Knowing the consonants carry the core meaning helps you see connections.

- Using study tools: Resources like Blue Letter Bible show both consonants and vowel points. Understanding what you're looking at makes these tools more useful.

- Appreciating the Masoretic achievement: The Masoretes devoted centuries to preserving pronunciation, accents, and textual notes. Their dedication made it possible for us to hear the scriptures approximately as ancient Israel heard them.

- Understanding textual discussions: When scholars debate whether a word should be read differently (like the divine name YHWH, pointed as Adonai), they're discussing the relationship between consonants and vowel points.

The most famous example of matres lectionis involves the divine name: יהוה (YHWH). These four consonants—Yod, He, Vav, He—form the name revealed to Moses at the burning bush (Exodus 3:14).

Out of reverence, Jews stopped pronouncing this name aloud, substituting Adonai (אֲדֹנָי, "Lord") when reading scripture. The Masoretes placed the vowel points of Adonai around the consonants YHWH as a reminder to make this substitution.

Medieval Christian scholars who didn't understand this convention read the consonants YHWH with the vowels of Adonai, producing the hybrid form "Jehovah"—a name that never existed in ancient Hebrew but became embedded in English tradition, including the King James Bible.

Modern scholars generally reconstruct the original pronunciation as Yahweh, though certainty is impossible since the name wasn't spoken aloud for millennia.

As you encounter Hebrew in your scripture study, remember:

- The 22 consonants carry the core meaning of words

- The matres lectionis (Aleph, Vav, Yod) hint at vowels in the original text

- The Masoretic niqqud preserves traditional pronunciation with dots and dashes

- The consonantal text is older and more authoritative; the vowel points represent one tradition of pronunciation

Next week we will build on this foundation as we examine specific Hebrew words in Genesis 6–11 and the story of Noah.

The Week 6 Study Guide contains six comprehensive files to support your study:

- Evidence of antiquity: specific parallels to 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, Book of Giants

- The weeping God in ancient Jewish and Christian sources

- The concept of Zion in ancient and modern context

- Translation in ancient and Restoration understanding

- The Flood in ANE context

- The Definition of Zion (Moses 7:18)

- The Weeping God (Moses 7:28–37)

- The Earth's Complaint (Moses 7:48)

- The Crucifixion Foreseen (Moses 7:55–56)

- The Return of Zion (Moses 7:62–64)

- Personal Study, Family Home Evening, Sunday School, Seminary/Institute, Relief Society/Elders Quorum, Primary, Missionary Teaching

As you study this week, consider:

- On Divine Emotion: What does it change to know that God weeps? How does this affect your understanding of His character and your relationship with Him?

- On Building Zion: Which of the three Zion qualities (unity, righteousness, no poor) is most needed in your family or community? What is one practical step toward that quality?

- On Agency: God gave agency "in the Garden of Eden" (Moses 7:32). How does this connect to His weeping? What does it teach about the cost of genuine love?

- On the Earth: What does it mean that the earth is "the mother of men" who cries out in weariness? How should this shape our relationship with creation?

- On Hope: The reunion described in Moses 7:63—the embrace, the kiss, the falling upon necks—what does this intimate language teach about what we're working toward?

In a world of theological systems that place God at infinite distance—impassible, unchanging, unmoved—Moses 7 reveals something radical: a Father who weeps.

Not a God who observes suffering with detached serenity. Not a divine clockmaker who set the universe in motion and stepped back. But a Father whose children's choices matter to Him. A God who gave agency knowing it would break His heart. A Creator who looks upon the workmanship of His own hands and weeps because they "hate their own blood."

This is not weakness. This is love.

And it is the kind of God who builds Zion—not by force, not by compulsion, but by invitation, by covenant, by patient longing for the day when "there was no poor among them" because they finally chose to become one.

Enoch saw that day. We're invited to build toward it.

Weekly Insights | CFM Corner | OT 2026 Week 06: Moses 7

Week 6

Moses 7

| Element | Details |

|---|---|

| Week | 06 |

| Dates | February 2–8, 2026 |

| Reading | Moses 7 |

| CFM Manual | Moses 7 Lesson |

| Total Chapters | 1 (69 verses in Moses 7) |

| Approximate Verses | 69 verses (expanded from 4 verses in Genesis 5:21–24) |

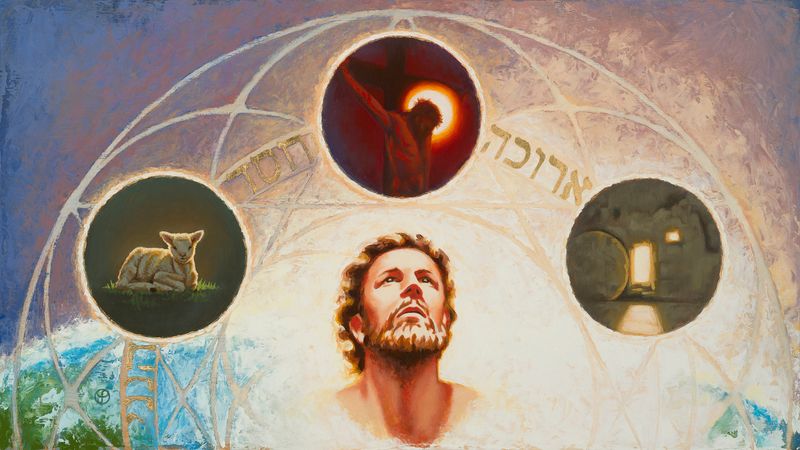

This week we encounter one of the most theologically significant chapters in all Restoration scripture. Moses 7 transforms four cryptic verses about Enoch in Genesis 5 into a 69-verse panoramic vision spanning from the pre-Flood world to the Second Coming. Where Genesis merely says Enoch "walked with God... and was not; for God took him" (Genesis 5:24), Moses 7 reveals what that walk entailed: a reluctant prophet becoming a mighty preacher, the establishment of a Zion community so righteous that an entire city was translated, and most remarkably, a vision in which Enoch beholds something unprecedented—God weeping.

Moses 7:1–20 continues from Moses 6, showing Enoch's prophetic ministry expanding to global scope. The prophet who once considered himself "but a lad" now speaks with power that shakes nations. Mountains flee, rivers change course, and enemies are terrified as Enoch preaches repentance. Yet the emphasis is not on miraculous power but on the community Enoch builds—a people who achieve a state of righteousness that warrants a special designation.

Moses 7:21–31 contains the defining verse for Latter-day Saint understanding of Zion: "The Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them" (Moses 7:18). This Zion community is then "taken up into heaven" (v. 21)—not just Enoch individually, but the entire city. Following this translation, Enoch's vision shifts to the "residue of the people" left behind, and he witnesses something that stops him in his tracks: God weeps.

Moses 7:32–40 presents Enoch's theological struggle with a weeping God. His question—"How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity?"—articulates the classic problem of divine impassibility: How can an eternal, infinite God experience grief? God's response reveals a Father whose creations are "the workmanship of mine own hands," who gave them agency in Eden, and who commanded them to "love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father." The weeping comes because "they are without affection, and they hate their own blood" (v. 33).

Moses 7:41–57 expands the vision as Enoch himself begins to weep. He witnesses the Flood, the spirit prison, and the entire panorama of human history. He sees "the day of the coming of the Son of Man, even in the flesh" (v. 47)—Christ's mortal ministry—and then "the Son of Man lifted up on the cross" (v. 55). At this moment, creation itself responds: "the heavens were veiled," "all the creations of God mourned," and "the earth groaned" (v. 56).

Moses 7:58–69 brings the vision to its climax with the promise of a latter-day Zion. Righteousness will "sweep the earth as with a flood" (v. 62), gathering the elect to a prepared place. And then Enoch's ancient city—held in reserve for thousands of years—will return: "Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there... and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other" (v. 63). The chapter ends with this reunion as the ultimate hope: two Zion communities embracing after millennia of separation.

Theme 1: The Weeping God—Divine Passibility and the Nature of Godhood

Perhaps no passage in Restoration scripture more directly challenges traditional Christian theology than Moses 7:28–37. The doctrine of divine impassibility—that God cannot suffer, change, or be affected by creatures—had been a cornerstone of classical theism since the Church Fathers merged biblical revelation with Greek philosophical categories. Augustine, Anselm, and Thomas Aquinas all affirmed that God is "without passions in the proper sense," incapable of emotional disturbance.

Enoch's question to God perfectly articulates this classical position: "How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity? And were it possible that man could number the particles of the earth, yea, millions of earths like this, it would not be a beginning to the number of thy creations; and thy curtains are stretched out still; and yet... the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains?" (Moses 7:29–31). How can a Being so vast, so eternal, so holy, be moved to tears by the actions of creatures so small?

God's response revolutionizes our understanding of divine nature. He does not deny His weeping or explain it away as anthropomorphism. Instead, He reveals the reason: these are "the workmanship of mine own hands" (v. 32). They are His children, to whom He gave agency "in the Garden of Eden" (v. 32). He commanded them to love and to choose Him as Father. But "they are without affection, and they hate their own blood" (v. 33).

The theological implications are profound. God's weeping is not weakness but love. A God who cannot grieve cannot truly love—love requires vulnerability to the beloved. President Spencer W. Kimball taught: "The Lord is not a static, impassive being. He has feelings, deep feelings, and He is affected by the conduct of His children" (as cited in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Spencer W. Kimball). The weeping God is not diminished by His tears; He is revealed as a Father whose children's choices genuinely matter to Him.

This theme connects directly to Week 05's teaching on the Fall and agency (Moses 6:48–56). The same agency that enables progression also enables rebellion. God cannot give agency without accepting that some will use it to choose misery. His weeping is the consequence of love that grants genuine freedom.

Theme 2: The Definition of Zion—One Heart, One Mind, No Poor

Moses 7:18 provides the scriptural definition that shapes Latter-day Saint understanding of Zion: "The Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them."

Notice what Zion is not in this definition. It is not primarily a geographical location, a political system, or even a temple. Zion is a people characterized by three qualities:

Unity ("one heart and one mind"): The Hebrew concept behind this phrase involves levav (לֵבָב, heart—the seat of will and emotion) and the unity of communal intention. The early Church in Acts achieved something similar: "the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul" (Acts 4:32). The Nephites after Christ's visit "were in one, the children of Christ" (4 Nephi 1:17). This is not uniformity that erases individuality but unity of purpose, covenantal commitment, and mutual love.

Righteousness ("dwelt in righteousness"): The Hebrew tsedaqah (צְדָקָה) implies right relationship—with God and with each other. Zion righteousness is not merely personal piety but covenantal fidelity that shapes community life.

Economic equality ("no poor among them"): This phrase echoes Deuteronomy 15:4—"there shall be no poor among you"—which describes the result of faithful observance of sabbatical year and jubilee laws. In Enoch's Zion, this equality came through consecration: "every man dealt justly with his neighbor" (implied in the broader context). The law of consecration revealed in D&C 42 and 82 follows this Enochian pattern.

President Brigham Young frequently referenced this verse: "We should have no poor; we should all be alike partakers of the good things of this world" (Journal of Discourses 19:47). The modern effort to build Zion involves not just personal sanctification but the creation of communities characterized by these three qualities.

Theme 3: Translation of an Entire City—Collective Righteousness and Collective Destiny

The translation of Enoch's city presents a remarkable doctrine: "Zion, in process of time, was taken up into heaven" (Moses 7:21). This was not merely Enoch's individual translation (as recorded in Genesis 5:24) but the collective translation of an entire community.

The phrase "in process of time" is significant. Translation was not instantaneous but gradual—the community grew in righteousness until reaching a threshold that qualified them for removal from the terrestrial sphere. Joseph Smith taught that translated beings inhabit "a place prepared for such characters... of the terrestrial order" (TPJS, 170), serving as "ministering angels unto many planets."

The theological significance is that righteousness can be communal, not just individual. Latter-day Saint theology emphasizes that we are saved as families and as covenant communities, not merely as isolated individuals. The celestial kingdom is described as a social order: "the same sociality which exists among us here will exist among us there, only it will be coupled with eternal glory" (D&C 130:2).

Enoch's translated city becomes the prototype for the latter-day Zion. The promise is that these two communities will eventually reunite: "Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other" (Moses 7:63). The embrace imagery suggests intimate reunion after long separation—the culmination of the gathering of Israel.

Theme 4: Prophetic Vision—From the Flood to the Second Coming

Moses 7 places Enoch among the great visionary prophets who saw the entire sweep of human history. Like Nephi (1 Nephi 11–14), the brother of Jared (Ether 3:25), and John the Revelator, Enoch received a panoramic vision extending from his day to the end of time.

The vision includes:

- The Flood: Enoch sees "the power of Satan" extending over the earth and God's decision to destroy the wicked by water (Moses 7:38–43)

- The Spirit Prison: Souls of the wicked "looking forth for the glory of God" and "for the day of their redemption from bondage" (Moses 7:38–39)

- Christ's Mortal Ministry: "The coming of the Son of Man, even in the flesh" (Moses 7:47)

- The Crucifixion: "The Son of Man lifted up on the cross" (Moses 7:55)

- Creation's Response: "The earth groaned... the rocks were rent" (Moses 7:56)

- The Latter-day Gathering: "Righteousness... sweep the earth as with a flood" (Moses 7:62)

- The Return of Zion: The reunion of the ancient and latter-day Zion communities (Moses 7:63)

- The Millennial Rest: A "thousand years shall the earth rest" (Moses 7:64)

- The End of Wickedness: The final judgment (Moses 7:65–67)

This panoramic vision demonstrates that prophets throughout history understood the plan of salvation in its fullness. The Atonement was not a late addition to God's plan but anticipated from before the foundation of the world.

Theme 5: The Earth's Covenant Relationship—A Living, Speaking, Suffering Creation

A remarkable feature of Moses 7 is the personification of the earth as a speaking, suffering, covenantal being. In Moses 7:48, Enoch hears "the earth ... saying: Wo, wo is me, the mother of men; I am pained, I am weary, because of the wickedness of my children. When shall I rest, and be cleansed from the filthiness which is gone forth out of me?"

This is not merely poetic personification. The earth speaks, mourns, and anticipates rest. At the crucifixion, "the earth groaned" (Moses 7:56). The earth has a covenantal relationship with its Creator and will eventually "rest" for a thousand years (Moses 7:64).

This theme connects to the broader Restoration teaching about creation's sentience. D&C 88:25–26 teaches that "the earth abideth the law of a celestial kingdom" and "shall be sanctified... and given to them who have kept the law." D&C 77:2 reveals that even animals "shall be saved" and "shall dwell in eternal felicity."

| Person | Role | Significance This Week |

|---|---|---|

| Enoch | Prophet, Builder of Zion | His ministry reaches culmination; he builds a community worthy of translation |

| God the Father | The Weeping God | Reveals His emotional nature; explains why He grieves over rebellious children |

| Satan | Adversary | Holds a "great chain" over the wicked; spreads "a great darkness over all the face of the earth" (Moses 7:26) |

| The People of Zion | Translated Community | Achieve the standard of righteousness that defines Zion |

| Noah | Preacher of Righteousness | Seen in vision as continuing Enoch's warning to a wicked generation |

| The Earth | Speaking, Covenantal Being | Cries out in weariness, anticipates rest |

Historical Period: Pre-Flood Era (Antediluvian World)

Approximate Dates: Traditional chronology places Enoch approximately seven generations after Adam. The genealogies in Genesis 5 suggest Enoch was born around 622 years after creation (using Masoretic text chronology) and was translated after 365 years of life.

Biblical Timeline Position: Moses 7 continues the Enoch material from Moses 6, covering the period between Enoch's prophetic call and the Flood (which comes in Moses 8 / Genesis 6–9).

Relationship to Previous Weeks

Week 04 (Genesis 3–4; Moses 4–5): Established the consequences of the Fall and the beginning of human wickedness through Cain's rebellion and the founding of secret combinations.

Week 05 (Genesis 5; Moses 6): Introduced Enoch's call, his reluctant acceptance of prophetic ministry, and the fundamental doctrines of the Fall, repentance, and baptism.

Week 06 (Moses 7): Brings Enoch's ministry to fulfillment. The doctrines taught in Moses 6 now produce fruit: a community righteous enough to be translated. The wickedness introduced in Moses 4–5 now reaches a level requiring divine intervention (the Flood).

Book of Moses (Chapter 7)

- Author: Moses, restored through Joseph Smith

- Source Date: Original to Moses (~1446 BC); restored December 1830

- Original Audience: Israel; through restoration, the whole Church

- Setting: Continuation of Moses's prophetic vision begun in Moses 1

- Purpose: To reveal Enoch's ministry, the establishment of Zion, and prophetic visions of human history

- Key Themes: Zion, divine emotion, translation, prophetic vision, latter-day gathering

- Literary Genre: Prophetic vision / apocalyptic narrative

Comparison with Genesis

| Genesis 5:21–24 | Moses 7 |

|---|---|

| 4 verses | 69 verses |

| "Enoch walked with God" | Details of Enoch's ministry and miracles |

| "God took him" | Entire city translated |

| No mention of Zion | Defines Zion (v. 18) |

| No emotion attributed to God | God weeps (vv. 28–37) |

| No prophetic visions | Panoramic vision from Flood to Second Coming |

Book of Mormon Connections

- 4 Nephi 1:1–3, 15–17: The post-Christ Nephite society achieved a Zion-like state: "no contentions... no poor among them"

- 3 Nephi 17:21–22: Jesus weeps among the Nephites—divine emotion displayed

- Ether 13:2–6: The New Jerusalem and the return of Enoch's city

Doctrine and Covenants Connections

- D&C 38:4: "I am the same which have taken the Zion of Enoch into mine own bosom"

- D&C 45:11–14: The return of Enoch's city

- D&C 84:99–100: "The Lord hath brought again Zion"

- D&C 97:21: "Zion is the pure in heart"

Pearl of Great Price Connections

- Moses 6:27–36: Enoch's call (continues into Moses 7)

- Abraham 2:6: The promise to gather the elect (echoes Moses 7:62)

- Divine Passibility: God has emotions; He can and does weep over His children's choices (Moses 7:28–37).

- The Definition of Zion: Zion is a people of one heart and one mind, dwelling in righteousness, with no poor among them (Moses 7:18).

- Collective Translation: An entire community can be translated based on collective righteousness (Moses 7:21).

- The Atonement Foreseen: Prophets from the earliest ages understood and anticipated Christ's sacrifice (Moses 7:45–47, 55–56).

- The Earth as Covenantal Being: The earth speaks, suffers, and anticipates rest (Moses 7:48, 61, 64).

- The Return of Zion: Enoch's translated city will return to meet the latter-day Zion (Moses 7:62–64).

- Agency Given in Eden: Agency is a gift given "in the Garden of Eden" (Moses 7:32), connecting back to Week 04's study of the Fall.

Moses 7 contains significant temple themes:

- Translation as Temple Ascent: The translation of Zion parallels temple imagery of ascending to God's presence. Just as priests ascend through temple spaces of increasing holiness, Enoch's community ascends to God's "abode" (Moses 7:21).

- The Divine Council: Enoch participates in a heavenly council, viewing earth from God's perspective—a temple theme of entering divine deliberations.

- Covenant Community: Zion's characteristics (unity, righteousness, consecration) parallel temple covenant expectations.

- The Return and Embrace: Moses 7:63 describes the reunion of two Zion communities in language reminiscent of temple ordinances: "we will receive them into our bosom... we will fall upon their necks... we will kiss each other."

Manual Focus: Understanding Zion and how we can help build it today.

Key Questions from Manual:

- What can we learn about God's nature from His weeping?

- How can our families and communities become "Zion"?

- What does it mean that Enoch's entire city was translated?

- How does the promise of Zion's return give us hope?

Manual's Suggested Activities:

- Identify specific ways to be "of one heart and one mind" with family members

- Discuss how to eliminate "poor among [us]" in practical, local ways

- Study the parallels between Enoch's Zion and the post-Christ Nephite society (4 Nephi)

If You Have Limited Time (Essential Reading):

- Moses 7:18 — Definition of Zion

- Moses 7:28–37 — God weeps

- Moses 7:62–64 — The return of Zion

If You Have More Time (Full Reading with Highlights):

- Read all 69 verses, noting:

- Every time emotion is attributed to God

- The progression from Enoch's ministry (vv. 1–20) to vision (vv. 21–67) to promise (vv. 62–69)

- How the earth is personified

For Deep Study:

- Compare Moses 7 with 1 Enoch (available online) to see similarities and differences

- Trace the "Zion" concept through D&C 57, 97, and 105

- Study President Brigham Young's teachings on building Zion (Journal of Discourses vols. 1, 2, 17)

The Weeping God (Scripture Central)

Taylor Halverson and Tyler Griffin discuss how Moses 7:28–37 challenges classical theology's doctrine of divine impassibility. The weeping God reveals a Father whose love makes Him vulnerable to His children's choices. This is not weakness but the necessary corollary of genuine love.

Zion as Community (Follow Him Podcast)

Hank Smith and John Bytheway explore how Moses 7:18 defines Zion in relational rather than geographical terms. Building Zion today means creating communities characterized by unity, righteousness, and economic equality—starting in our own homes.

The Return of Enoch's City (Interpreter Foundation)

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw's essays on Moses 7 explore the ancient Enoch traditions and how Moses 7 both draws from and transforms them. The promise of Zion's return provides the hope that sustains the gathering of Israel.

Translation and Terrestrial Order (LDS Perspectives)

Discussion of Joseph Smith's teachings on translated beings and their role as "ministering angels unto many planets." Enoch's city has not been idle during its millennia of separation from earth.

| File | Content Focus |

|---|---|

| 01_Week_Overview | This overview document |

| 02_Historical_Cultural_Context | Ancient Enoch traditions, 1 Enoch parallels, divine impassibility in Christian history |

| 03_Key_Passages_Study | Detailed analysis of key verses with cross-references |

| 04_Word_Studies | Hebrew terms: Tsiyon, bakah (weep), echad (one), laqach (take/translate) |

| 05_Teaching_Applications | Personal study, family, Sunday School, Seminary applications |

| 06_Study_Questions | 180 questions for individual and group study |

What This Section Covers:

- Historical Setting — Quick-reference overview of dates and context

- Evidence of Antiquity — Why Moses 7 contains details Joseph Smith couldn't have known

- Overview of Ancient Enoch Traditions — The rich background of Enoch literature

- The Biblical Foundation — The mysterious four verses in Genesis

- Extra-Biblical Enoch Literature — 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, 3 Enoch, Book of Giants

- The Weeping God — Challenging divine impassibility

- The Concept of Zion — From place to people

- Translation — Individual vs. collective translation

- The Flood in Ancient Context — ANE parallels

- The Earth as Covenantal Being — The personified earth

- Apocalyptic Literature — Moses 7's literary genre

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Events Described | Enoch's grand vision—from his ministry through the Flood to the Second Coming |

| Narrative Timeframe | ~3000 BC (traditional); seventh generation from Adam |

| Moses 7 Restoration | June–October 1830, Joseph Smith's inspired revision of the Bible |

| Zion's Development | 365 years of communal righteousness before translation (Moses 7:68) |

| Vision Scope | Antediluvian era → Flood → Christ's ministry → Apostasy → Restoration → Millennium |

| Key Ancient Parallels | 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, 3 Enoch, Book of Giants (Qumran), Midrash, Mandaean texts |

Moses 7 presents Enoch's sweeping vision of human history—from the wickedness that surrounded him to the triumphant return of Zion at the Second Coming. This chapter is unparalleled in scripture for its emotional intensity (a God who weeps), its communal theology (an entire city translated), and its eschatological scope (spanning millennia in a single vision). The recording of this vision came through Joseph Smith in 1830, but the content resonates with ancient Enoch traditions preserved across multiple cultures—traditions largely unavailable to Joseph Smith.

Recent scholarship has identified striking parallels between specific details in Moses 7 and ancient texts that Joseph Smith could not have known. These parallels strengthen the case for the ancient origins of the Book of Moses.

Summary of Ancient Parallels

| Detail in Moses 7 | Ancient Parallel | Discovery/Access Date |

|---|---|---|

| God weeps (7:28-29) | 1 Enoch, Midrash Rabbah, Zohar, Apocalypse of Paul | Not available in English 1830 |

| Heavens weep (7:28, 40) | Midrash, Jewish tradition (Creation weeping) | Hebrew/Aramaic texts unavailable 1830 |

| Earth as "mother of men" complaining (7:48) | Book of Giants (4Q203), 1 Enoch 7–9 | Qumran discovery 1948 |

| Enoch receives "right to throne" (7:59) | Nineveh tablet (pre-1100 BC), 1 Enoch, 3 Enoch | Not translated until 20th century |

| Enoch "clothed with glory" (7:3) | 2 Enoch 22:8-10 (celestial clothing) | First English translation 1896 |

| Collective translation of Zion (7:21, 69) | Mandaean fragments, late midrash | 19th century (Western access) |

| "Bosom" imagery (6× in ch. 7) | Second Temple "Abraham's bosom" tradition | Scholarly analysis 20th century |

| Giants "stood afar off" (7:15) | Book of Giants: righteous on "skirts of four huge mountains" | Qumran discovery 1948 |

Each parallel is explored in detail below and in the Key Passages file.

The Weeping God: An Ancient Motif (Moses 7:28–37)

The portrayal of a weeping God in Moses 7 has no parallel in the Bible—yet it appears prominently in ancient Jewish and early Christian sources unknown to Joseph Smith:

1 Enoch (Book of Parables): Enoch "wept bitterly" over the wickedness of mankind, and heaven joins in his sorrow.

Midrash Rabbah on Lamentations: God Himself weeps at the destruction of the temple. When the angels try to stop Him, God replies: "If thou lettest Me not weep now, I will repair to a place which thou hast not permission to enter, and will weep there."

Apocalypse of Paul: The apostle meets Enoch "within the gate of Paradise" and sees him weep. Enoch explains: "We are hurt by men, and they grieve us greatly."

Zohar: A full "chorus of weeping" begins with the Messiah and expands to include all heaven.

As Hugh Nibley observed: "There is, to say the least, no gloating in heaven over the fate of the wicked world. [And it] is Enoch who leads the weeping."

Source: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, "The Weeping of Enoch" (Interpreter Foundation, Essay #28)

The Complaining Earth: "Mother of Men" (Moses 7:48)

Moses 7:48 presents the earth speaking as "the mother of men," asking to be cleansed from wickedness. This precise motif appears nowhere in the Bible—but it does appear in the Dead Sea Scrolls:

Book of Giants (4Q203, Frag. 8:6–12): > "Through your fornication on the earth, and it (the earth) has [risen up ag]ainst y[ou and is crying out] and raising accusation against you."

1 Enoch 7:4–6; 8:4: > "The earth, devoid (of inhabitants), raises the voice of their cries to the gates of heaven."

Andrew Skinner notes three key correspondences between Moses 7 and the Qumran text:

- Nature of wickedness: Book of Giants uses "fornication" (Aramaic znwtkwn), semantically equivalent to Moses 7's "filthiness"

- Direct complaint: Both texts have the earth itself complaining

- Plea for cleansing: Both anticipate destruction to cleanse the earth

Why This Matters: The Book of Giants was not discovered until 1948 at Qumran and not translated until decades later. Joseph Smith could not have known this text.

Source: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, "The Complaining Voice of the Earth" (Interpreter Foundation, Essay #26); Andrew C. Skinner, "Joseph Smith Vindicated Again"

Enoch's Transfiguration and Throne Rights (Moses 7:3, 59)

Moses 7:3 describes Enoch being "clothed upon with glory," and 7:59 states that God has "given unto me a right to thy throne." Both concepts have striking ancient parallels:

2 Enoch 22:8–10 (Slavonic): > "And the Lord said to Michael, 'Go, and extract Enoch from his earthly clothing. And anoint him with my delightful oil, and put him into the clothes of my glory.' ... And I looked at myself, and I had become like one of his glorious ones."

Nineveh Tablet (pre-1100 BC): An ancient tablet describes Enmeduranki (identified with Enoch by scholars) being "set on a large throne of gold" by the gods.

1 Enoch Book of Parables 45:3: > God's Chosen One "will sit on the throne of glory."

3 Enoch: > Enoch declares: "He (God) made me a throne like the throne of glory."

Hugh Nibley showed these parallels to Matthew Black, a prominent Enoch scholar. Nibley later reported that they "really knocked Professor Black over. … It really staggered him."

Source: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, "Enoch's Transfiguration" (Interpreter Foundation, Essay #22)

Collective Translation: Unique to Moses 7

While individual translation (Enoch, Elijah) appears across cultures, the translation of an entire community is virtually unique to Moses 7—yet ancient sources hint at this possibility:

Mandaean Enoch Fragments: Describe others besides Enoch ascending bodily with him.

Late Midrash: Contains traditions of group ascension with righteous leaders.

As David Larsen notes: "Can an entire community ascend to heaven?" Moses 7 answers affirmatively—a concept with few parallels in world literature but attested in fragmentary ancient sources.

Source: Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, "God Receives Zion" (Interpreter Foundation, Essay #30); David J. Larsen, "Enoch and the City of Zion" (BYU Studies)

For Further Study: Interpreter Foundation Essays

The following essays from Jeffrey M. Bradshaw's "Book of Moses Essay Series" directly address Moses 7's ancient parallels:

| Essay # | Title | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| #22 | Enoch's Transfiguration | Celestial clothing, 2 Enoch parallels |

| #24 | End of the Wicked, Beginnings of Zion | Book of Giants parallels, decisive battle |

| #25 | A Chorus of Weeping | Structure of weeping motif |

| #26 | The Complaining Voice of the Earth | Qumran parallels to earth's complaint |

| #27 | The Weeping Voice of the Heavens | Creation weeping at Flood |

| #28 | The Weeping of Enoch | Ancient sources on Enoch's weeping |

| #29 | The Earth Shall Rest | Eschatological parallels |

| #30 | God Receives Zion | Collective translation, "bosom" imagery |

The figure of Enoch occupies a unique place in ancient religious imagination. Despite receiving only four verses in Genesis (5:21–24), Enoch generated more extra-biblical literature than perhaps any other Old Testament figure. The cryptic phrase "Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him" sparked centuries of speculation about what this patriarch experienced, learned, and revealed.

Moses 7 enters this rich tradition not as a late invention but as a Restoration of what was always known about Enoch among the covenant people—knowledge preserved in fragmentary form across multiple ancient traditions and now restored in fullness through prophetic revelation.

The Mysterious Four Verses

The Hebrew text of Genesis 5:21–24 reads:

> וַיְחִי חֲנוֹךְ חָמֵשׁ וְשִׁשִּׁים שָׁנָה וַיּוֹלֶד אֶת־מְתוּשָׁלַח׃ וַיִּתְהַלֵּךְ חֲנוֹךְ אֶת־הָאֱלֹהִים אַחֲרֵי הוֹלִידוֹ אֶת־מְתוּשֶׁלַח שְׁלֹשׁ מֵאוֹת שָׁנָה וַיּוֹלֶד בָּנִים וּבָנוֹת׃ וַיְהִי כָּל־יְמֵי חֲנוֹךְ חָמֵשׁ וְשִׁשִּׁים שָׁנָה וּשְׁלֹשׁ מֵאוֹת שָׁנָה׃ וַיִּתְהַלֵּךְ חֲנוֹךְ אֶת־הָאֱלֹהִים וְאֵינֶנּוּ כִּי־לָקַח אֹתוֹ אֱלֹהִים׃

Translation: "And Enoch lived sixty-five years and begat Methuselah. And Enoch walked with God after he begat Methuselah three hundred years, and begat sons and daughters. And all the days of Enoch were three hundred sixty-five years. And Enoch walked with God, and he was not, for God took him."

Key Phrases and Their Significance

"Walked with God" (וַיִּתְהַלֵּךְ... אֶת־הָאֱלֹהִים): The verb hithallek (הִתְהַלֵּךְ) is the hithpael (reflexive) form of halak (to walk). This form appears only twice in Genesis 5 (for Enoch) and is also used of Noah (Genesis 6:9). The preposition et (אֶת) suggests intimate companionship—walking "with" God rather than merely "before" Him.

"He was not" (וְאֵינֶנּוּ): This phrase (einenu) literally means "and-he-was-not-there." It does not say he died; it says he ceased to be present. The contrast with other Genesis 5 patriarchs is stark—each ends with "and he died" (וַיָּמֹת), but Enoch's entry conspicuously lacks this formula.

"God took him" (לָקַח אֹתוֹ אֱלֹהִים): The verb laqach (לָקַח) means "to take, receive, fetch." It is used for taking a wife (Genesis 4:19), receiving instruction (Proverbs 4:2), and being taken by God. The same root appears when Elijah is "taken" (2 Kings 2:10). God actively removed Enoch from earthly existence.

365 Years: The number 365—the days in a solar year—may carry symbolic weight. In Mesopotamian tradition, the sun god Shamash was associated with cosmic knowledge. Enoch's lifespan matching the solar year may hint at his acquisition of celestial/cosmological wisdom.

1 Enoch (Ethiopic Enoch)

The most extensive and influential Enoch text is 1 Enoch, preserved in Ethiopic (Ge'ez) and representing traditions that may date to the 3rd century BC. It was considered scripture by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and was quoted in the New Testament (Jude 1:14–15).

Structure of 1 Enoch

| Section | Chapters | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Book of the Watchers | 1–36 | Fallen angels (Watchers) corrupt humanity; Enoch intercedes; tours of heaven and Sheol |

| Book of Parables (Similitudes) | 37–71 | Messianic visions; the "Son of Man"; eschatological judgment |

| Astronomical Book | 72–82 | Solar and lunar calendars; cosmic mechanics |

| Book of Dream Visions | 83–90 | Animal Apocalypse (history as animals); Flood visions |

| Epistle of Enoch | 91–108 | Woe oracles; ethical exhortations; Apocalypse of Weeks |

The Watchers Tradition

The Book of the Watchers expands Genesis 6:1–4 (the "sons of God" marrying "daughters of men") into a full narrative of angelic rebellion. Two hundred angels, led by Shemihazah and Azazel, descend to Mount Hermon, take human wives, and teach forbidden knowledge:

- Azazel teaches metalworking, weapons, and cosmetics

- Shemihazah leads the angelic corruption

- Their offspring, the Nephilim/Giants, wreak havoc

The term "Nephilim" derives from the Hebrew naphal (to fall), suggesting these were "fallen ones"—not merely physical giants but beings with extraordinary capacity who chose apostasy over righteousness. (See expanded discussion under "The Book of Giants" below.)

Enoch is called to pronounce judgment on these rebellious angels—a remarkable role where a mortal prophet judges celestial beings.

Parallels with Moses 7

| 1 Enoch | Moses 7 |

|---|---|

| Enoch ascends to heaven | Enoch's vision shows him "all the inhabitants of the earth" (7:21) |

| Enoch sees cosmic secrets | Enoch sees history from Flood to Second Coming |

| Enoch intercedes for fallen angels | Enoch weeps with God over wicked humanity |

| Emphasis on cosmological knowledge | Emphasis on ethical community (Zion) |

| Enoch as cosmic tour guide | Enoch as community builder and prophet |

2 Enoch (Slavonic Enoch)

2 Enoch, preserved in Old Church Slavonic, describes Enoch's ascent through seven (or ten) heavens. In the seventh heaven, Enoch encounters God's throne and is transformed:

> "And the Lord said to Michael, 'Go, and extract Enoch from his earthly clothing. And anoint him with my delightful oil, and put him into the clothes of my glory.' And Michael did as the Lord had said to him. He anointed me and he clothed me. And the appearance of that oil is greater than the greatest light, and its ointment is like sweet dew, and its fragrance like myrrh; and it is like the rays of the glittering sun. And I looked at myself, and I had become like one of his glorious ones, and there was no observable difference." (2 Enoch 22:8–10, Andersen translation)

This transformation motif—a mortal becoming glorious—resonates with Latter-day Saint temple theology but is absent from Moses 7's emphasis on community rather than individual transformation.

3 Enoch (Hebrew Enoch / Sefer Hekhalot)

3 Enoch, a later Jewish mystical text (perhaps 5th–6th century AD), presents Enoch as transformed into the angel Metatron, "the lesser YHWH." Rabbi Ishmael ascends to heaven and learns from Metatron/Enoch the secrets of the heavenly realm.

Key features:

- Enoch becomes the highest angel

- He possesses 72 names

- He is called "Prince of the Divine Presence"

- He serves as heavenly scribe

The Book of Giants

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls (Qumran), fragments of the "Book of Giants" survive. This text, related to 1 Enoch, expands the Watchers narrative and includes the giants having troubling dreams that Enoch interprets. Hugh Nibley extensively analyzed parallels between the Book of Giants and the Book of Moses.

The Nephilim as "Fallen Ones"

The term Nephilim (נְפִילִים) in Genesis 6:4 and Numbers 13:33 is often translated as "giants," but this may obscure the deeper meaning embedded in the Hebrew root. The word derives from naphal (נָפַל), meaning "to fall." This etymology suggests that the Nephilim were not primarily defined by their physical stature but by their spiritual condition—they were "the fallen ones."

Book of Giants Interpretation:

The Book of Giants (4Q203, 4Q530-532, 6Q8) provides crucial context for understanding the Nephilim. In this text, the "giants" are portrayed not merely as physically large beings but as morally corrupt individuals who:

- Possessed extraordinary knowledge: They inherited forbidden wisdom from the Watchers—metallurgy, enchantments, astrology, and warfare techniques

- Used that knowledge for selfish ends: Rather than blessing humanity, they exploited their advantages for personal power and domination

- Brought destruction upon the earth: Their violence and corruption necessitated divine judgment

The Book of Giants presents these figures as receiving prophetic dreams warning them of their impending destruction—dreams that only Enoch could interpret. Their "falling" was not from heaven (as with the Watchers/angels) but from their potential. They were beings with great capacity who chose apostasy over righteousness.

A Pattern of "Fallen Ones":

This interpretation illuminates a recurring scriptural pattern—individuals or groups with extraordinary knowledge and capacity who use it for selfish ambitions rather than covenant purposes:

| Figure/Group | Great Capacity | The Fall | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lucifer | "Son of the Morning," highest status in premortal realm | Sought God's power and glory for himself | Isaiah 14:12; Moses 4:1-4 |

| Cain | Knew God personally, received divine instruction | Loved Satan more than God; murdered Abel for gain | Moses 5:16-31 |

| Pre-Flood Nephilim | Sons of God, inherited divine knowledge | Used knowledge for violence and corruption | Genesis 6:1-4; Book of Giants |

| Korihor | Highly intelligent, persuasive teacher | Used abilities to lead people from faith | Alma 30 |

| Sons of Perdition | Knew God's power, had the Holy Ghost | Denied after perfect knowledge | D&C 76:31-35 |

Connection to Moses 7:

Moses 7:15 describes how "the giants of the land, also, stood afar off" when faced with Enoch's preaching. The Book of Giants (4Q531) similarly describes the righteous gathering on "the skirts of four huge mountains" while the giants await judgment. In both texts, the Nephilim are portrayed as those who had opportunity for righteousness but chose otherwise—their "falling" being a moral descent rather than physical.

This understanding transforms the "giants" from mythological monsters into a sobering warning: those with the greatest capacity bear the greatest responsibility. To possess covenant knowledge and priesthood power while pursuing selfish ambitions is to become one of the "fallen ones."

Why This Matters for Moses 7:

Understanding the Nephilim as "fallen ones" deepens our appreciation for Enoch's achievement. While the Nephilim used their knowledge to dominate and destroy, Enoch used his to build Zion—a community "of one heart and one mind" with "no poor among them" (Moses 7:18). The contrast is deliberate: the same generation that produced the Nephilim also produced Zion. Access to divine knowledge does not determine outcomes; how we use that knowledge does.

| Feature | 1 Enoch / 2 Enoch / 3 Enoch | Moses 7 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Cosmological secrets, angelic hierarchies | Ethical community, Zion |

| Enoch's Role | Tour guide through heavens, angelic judge | Prophet, community builder |

| Translation | Individual transformation | Collective translation of city |

| Divine Emotion | God is distant judge | God weeps |

| Social Concern | Minimal | Central: "no poor among them" |

| Christology | "Son of Man" figure (ambiguous) | Explicit Christ prophecy (7:47, 55) |

| Last Days | Eschatological judgment | Zion's return, reunion of communities |

Significance of the Differences

Moses 7 does not simply copy from ancient Enoch traditions—it transforms them. Where 1 Enoch emphasizes Enoch's acquisition of secret knowledge, Moses 7 emphasizes his creation of a righteous community. Where 2 Enoch focuses on individual transformation, Moses 7 focuses on collective translation. Where traditional Enoch literature presents God as distant cosmic ruler, Moses 7 reveals a weeping Father.

These differences suggest that Moses 7 represents an independent tradition—or, in Latter-day Saint understanding, the original tradition from which the others derive in fragmentary, corrupted form.

Classical Theism and Divine Impassibility

The doctrine of divine impassibility—that God cannot suffer, change, or be affected by creatures—became a cornerstone of classical Christian theology as the Church Fathers synthesized biblical revelation with Greek philosophical categories.

Key Figures

Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BC – 50 AD): Jewish philosopher who heavily influenced Christian thought. Philo argued that God is utterly transcendent and unchanging. Anthropomorphic language about God (hands, eyes, emotions) must be understood allegorically.

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD): Affirmed that God's love is not "passion" in the sense of emotional disturbance. God loves but is not affected by that love in the way humans are affected.

Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109 AD): In the Proslogion, Anselm wrote: "Thou art compassionate in terms of our experience, and not compassionate in terms of thy being." God appears compassionate from our perspective but experiences no actual emotion.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 AD): In the Summa Theologica, Aquinas argued that God has no "passions" (emotional states caused by external agents). Divine "anger" or "love" must be understood as God willing certain effects, not experiencing emotional states.

The Philosophical Background

This doctrine derived from Greek philosophy, particularly:

Plato: The ideal Forms are perfect, unchanging, beyond affection by the material world. If God is perfect, He must be similarly unchanging.

Aristotle: The "Unmoved Mover" is pure actuality, with no potentiality. Change implies movement from potential to actual, which would indicate imperfection in God.

Stoicism: The goal of the sage is apatheia—freedom from passion. If human perfection involves emotional detachment, divine perfection must even more so.

Moses 7's Radical Alternative

Against this entire tradition, Moses 7 presents a God who weeps. The text offers no apology, no allegorical interpretation. God Himself explains the reason for His weeping: His children—"the workmanship of mine own hands"—have rejected Him and become "without affection" (Moses 7:32–33).

Latter-day Saint theology, informed by additional revelation, rejects divine impassibility:

- D&C 76:1 describes "the great love of our Father"

- D&C 121:7–8 implies divine empathy with human suffering

- The Atonement itself involves God experiencing the full range of human pain

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland taught: "I am convinced that in the garden and on the cross, the weight of human sin and sorrow was placed upon a Being who knew no sin, who felt with perfect clarity every one of our transgressions and shortcomings" ("None Were With Him," General Conference, April 2009). A God who can suffer in the Atonement is a God who can weep over His children's choices.

Biblical Development of "Zion"

The term Tsiyon (צִיּוֹן) appears 152 times in the Hebrew Bible, undergoing significant semantic development:

| Period | Meaning | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Jebusite/Early Davidic | A specific fortress/hill | 2 Samuel 5:7: "David took the stronghold of Zion" |

| Temple Era | Mount Moriah, Temple Mount | Psalm 132:13: "The LORD hath chosen Zion" |

| Poetic/Prophetic | Jerusalem as a whole | Isaiah 2:3: "Out of Zion shall go forth the law" |

| Eschatological | Future gathering place | Micah 4:2: "The mountain of the house of the LORD" |

| Personified | Daughter Zion (people) | Isaiah 52:2: "Shake thyself from the dust... O captive daughter of Zion" |

Etymology Debate

The etymology of Tsiyon remains uncertain:

- *From tsun (צון):* "to protect" — Zion as fortress/citadel

- *From tsiyyah (צִיָּה):* "dry/parched land" — possibly referring to terrain

- *From tsiyun (צִיּוּן):* "marker/monument" — Zion as memorial or sign

Moses 7's Redefinition

Moses 7:18 provides a definition unique in scripture: "The Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them."

This shifts Zion from geography to character:

- Zion is not primarily a place but a people

- The defining characteristics are ethical, not locational

- Three marks: unity, righteousness, economic equality

This redefinition has profound implications for Latter-day Saint theology. President Spencer W. Kimball taught: "May I suggest three things that we must do to establish Zion... First, we must eliminate the individual tendency to selfishness... Second, we must cooperate completely and work in harmony... Third, we must lay on the altar and sacrifice whatever is required by the Lord" ("Becoming the Pure in Heart," General Conference, April 1978).

Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical Parallels

The concept of humans being taken to heaven without dying appears across cultures:

| Tradition | Figure | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hebrew Bible | Enoch (Genesis 5:24) | "God took him" |

| Hebrew Bible | Elijah (2 Kings 2:11) | "Went up by a whirlwind into heaven" |

| Greek Mythology | Ganymede | Taken to Olympus by Zeus |

| Greek Mythology | Heracles | Assumed into divine status |

| Roman Tradition | Romulus | Disappeared; assumed into heaven |

| Mesopotamian | Utnapishtim | Granted immortality after Flood |

Collective Translation: Unique to Moses 7

What sets Moses 7 apart is the translation of an entire community, not just an individual. "Zion, in process of time, was taken up into heaven" (Moses 7:21).

This collective translation has few if any parallels in world literature. It establishes a pattern:

- Righteousness is communal, not just individual

- Salvation involves covenant community

- The celestial goal is social, not solitary

Joseph Smith's Clarification

Joseph Smith taught that translated beings:

- Do not immediately enter God's presence in fullness

- Inhabit "a place prepared for such characters... of the terrestrial order"

- Serve as "ministering angels unto many planets" (TPJS, 170)

This suggests that Enoch's city has not been idle during the millennia since translation. The community continues its work of ministry on a cosmic scale.

Mesopotamian Flood Traditions

Moses 7:38–52 positions the Flood within Enoch's prophetic vision. This narrative connects to broader ANE traditions:

Gilgamesh Epic (Tablet XI)

Utnapishtim, the Babylonian Noah figure, tells Gilgamesh how he survived the divine flood:

- The gods decided to destroy humanity

- Ea warned Utnapishtim to build a boat

- He loaded family, craftsmen, and "seed of all living creatures"

- After seven days, the flood subsided

- He sent out birds (dove, swallow, raven)

- He offered sacrifice

Atrahasis Epic

An earlier Akkadian text providing more backstory:

- Humanity's noise disturbed the gods' sleep

- The gods sent plague, then drought, then flood

- Enki (Ea) warned Atrahasis

- Similar boat-building and survival

Sumerian Flood Story

The oldest version, featuring Ziusudra as the hero.

Distinctive Elements in Moses 7

Moses 7's flood narrative differs from ANE parallels in crucial ways:

| ANE Traditions | Moses 7 |

|---|---|

| Gods annoyed by human noise | God grieves over human wickedness |

| Capricious divine decision | Moral cause: "among all the workmanship of mine hands there has not been so great wickedness" (7:36) |

| One god warns hero secretly | God openly announces judgment through Enoch |

| Focus on hero's survival | Focus on God's emotional response |

| No redemption for drowned | "Spirits in prison" await redemption (7:38–39) |

The "spirits in prison" concept anticipates 1 Peter 3:19–20 and the Latter-day Saint doctrine of work for the dead. Even those destroyed in the Flood are not beyond redemption's reach.

Personification in Moses 7

Moses 7:48–49 presents a remarkable personification:

> "And it came to pass that Enoch looked upon the earth; and he heard a voice from the bowels thereof, saying: Wo, wo is me, the mother of men; I am pained, I am weary, because of the wickedness of my children. When shall I rest, and be cleansed from the filthiness which is gone forth out of me? When will my Creator sanctify me, that I may rest, and righteousness for a season abide upon my face?"

Ancient Near Eastern Background

Personification of the earth appears in various ANE traditions:

- Sumerian: Ki (earth) as divine being, mother of gods

- Egyptian: Geb (earth god) and Nut (sky goddess)

- Greek: Gaia as primordial earth goddess

However, these are typically deities in their own right. Moses 7 presents the earth as a covenantal being in relationship with its Creator—not a goddess but a created entity with sentience and moral concern.

Restoration Expansion

Latter-day revelation expands this concept:

- D&C 88:25–26: "The earth abideth the law of a celestial kingdom... it shall be sanctified"

- D&C 77:2: "That which is spiritual being in the likeness of that which is temporal... the spirit of man in the likeness of his person"

- D&C 130:9: "This earth, in its sanctified and immortal state, will be made like unto crystal"

The earth's groaning (Moses 7:56) at the crucifixion and its promised "rest" for a thousand years (Moses 7:64) suggest ongoing covenantal relationship between creation and Creator.

Characteristics of Jewish Apocalyptic

Moses 7 shares features with Jewish apocalyptic literature (Daniel, 1 Enoch, 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch):

- Heavenly Visions: Prophet sees from cosmic/divine perspective

- Historical Sweep: Vision spans from past to eschatological future

- Angelic Mediation: Heavenly beings explain visions

- Symbolic Imagery: Animals, numbers, cosmic phenomena

- Dualistic Conflict: Good vs. evil on universal scale

- Eschatological Hope: Vindication of the righteous at the end

Unique Elements in Moses 7

While sharing apocalyptic features, Moses 7 differs significantly:

| Typical Apocalyptic | Moses 7 |

|---|---|

| Pessimistic about present age | Hope through Zion community |

| Focus on cosmic speculation | Focus on ethical community |

| God as distant judge | God as weeping Father |

| Secret knowledge for elite | Community righteousness available to all |

| Coded symbols requiring interpretation | Relatively straightforward narrative |

Moses 7 uses apocalyptic framework but fills it with prophetic (ethical) content. The goal is not esoteric knowledge but Zion community.

- Why might Genesis preserve only four verses about Enoch when such extensive traditions existed?

- How does Moses 7's portrait of a weeping God affect your understanding of divine nature?

- What would it look like to apply the Moses 7:18 definition of Zion to your family? Your ward?

- How does the concept of collective translation (a whole city) change our understanding of salvation?

- What is the significance of the earth being portrayed as a speaking, suffering being?

- How do the "spirits in prison" (Moses 7:38) connect to temple work for the dead?

Ancient Enoch Literature

- R.H. Charles, The Book of Enoch (1917) — Classic translation of 1 Enoch

- F.I. Andersen, "2 Enoch" in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol. 1

- P.S. Alexander, "3 Enoch" in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol. 1

- J.T. Milik, The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments from Qumran

Hugh Nibley on Enoch

- Enoch the Prophet (Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Vol. 2)